The Royal Munster Fusiliers

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 1 (Spring 1998), Volume 6A remarkable period in Ireland’s military history ended when the British army’s five southern Irish regiments were disbanded in 1922.The Royal Irish Regiment and the Connaught Rangers had been raised in Ireland from about 1683 and 1793 respectively, while the Leinster Regiment, the Royal Dublin Fusiliers and the Royal Munster Fusiliers had originated as Canadian or Indian regiments. Despite a tradition of nationalist opposition to recruiting for the British Army and although generally officered by Britons or Protestant unionists, the ranks of these regiments were filled mainly by Irish Catholics.

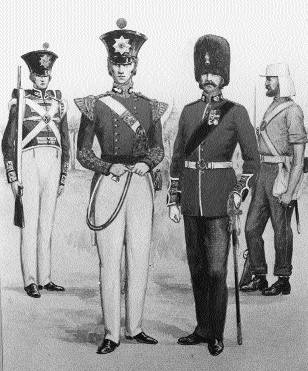

Uniforms of the regiments which were forerunners of the Royal Munster Fusiliers, 1828-68. Note the ‘Dirty Shirt’ to the right. (National Army Museum, London)

An army of occupation?

There is substance to the claim that the army in Ireland was one of occupation. It had a long history of campaigning against nationalist forces and was also active in the nineteenth-century Land War. By the turn of the century numerous barracks designed to aid in policing and the suppression of rebellion were scattered throughout Ireland. The garrison of mainly British regiments fluctuated between about 25,000 and 30,000 troops. In 1904 there was accommodation for 1,318 officers, 95 warrant officers, and 33,173 non-commissioned officers and men. This number was significantly disproportionate to garrisons elsewhere in the United Kingdom.

However, large numbers of Catholic Irishmen served in the army even when it was technically unlawful for them to do so. In 1830, although representing only 32.2 per cent of the United Kingdom’s population, the Irish contributed 42 per cent of the army’s manpower. This fell to 27.9 per cent by 1870 after famine and emigration had decimated the country’s population. But the numbers enlisting were still significantly disproportionate to the total UK population.

There followed a steady decline in the number of Irish recruits but the Irish contribution remained significant. In 1912, when Ireland’s population was 9.9 per cent of the UK’s Irish recruits made up 9.1 per cent of non-commissioned officers and men in the army.

A popular institution?

The large numbers of unemployed, impoverished or educationally disadvantaged Irishmen joining its ranks were given purpose by the army. It provided them with comradeship, warmth, shelter, security and future prospects. Travel, adventure and excitement replaced crushing boredom. Moreover, in an Ireland which formed an integral part of the United Kingdom, such men thought of themselves as joining ‘the Army’, rather than ‘the British Army’.

The army garrison in Ireland was also an important contributor to local economies and social life. And among Irish people of all classes, regardless of political persuasion, there was pride in what was widely perceived as the unique fighting qualities of Catholic Irish soldiers. Nationalists who passionately condemned enlistment in the army could also publicly acclaim the bravery of Irish soldiers, admire their feats of arms in the imperial cause, and glory in the fighting reputation of the Irish regiments.

Fear that the army ‘anglicised’ Irish men was a recurring theme in nationalist thinking and rhetoric. Although generally remaining vigorously conscious of their Irish identity, the army’s regimental system could effectively subvert Irish soldiers’ loyalty to institutions other than the regiment to which they belonged.

The regiment

For a great many men the regiment was ‘home’. It was the focus of pride and honour. Members shared a powerful esprit de corps

The second day of the battle of Ferozeshah (first Sikh war), 22 December 1845. The 1st Bengal European Regiment participated and it appeared as a battle honour on the colours of the 1st Battalion Royal Munster Fusiliers. (National Army Museum, London)

Described by one writer as a ‘finite and sacred body’, the regiment’s colours, emblazoned with its ‘battle honours’ and often defended to the death, symbolised its ‘spiritual’ nature. Loyalty to the regiment was intensified by the imperial nature of the British Army. Men could be away from Ireland for years, sharing their lives and dangers with fellow Irish, English, Scots or Welsh men during campaigns in distant lands.

The Royal Munster Fusiliers were representative of southern Ireland’s military contribution to the imperial cause. Described by Lord Dunraven in 1918 as a regiment whose bones came from Bengal but whose blood and sinews were Irish, it was formed from two of the Honourable East India Company’s regiments.

Imperial origins

The regiment’s roots can be traced to an officer and thirty European soldiers employed by the East India Company in 1652 to protect its factory near Calcutta. Considered by some as being ‘pretty desperate crews: adventurers, mercenaries, deserters from the armies of foreign powers and the assorted riffraff which made up the European population of India at the time’, this force developed into a professional military unit as the Company’s trade and influence expanded. As the 1st Bengal European Regiment, it won its first battle honour at Plassey in June 1757 under the command of Robert Clive.

The regiment saw action against the Sikhs, Indian princes, the French and the Dutch. It also campaigned in Java, Afghanistan and Burma. In 1832 Frederick Sleigh Roberts, who later won the Victoria Cross and become a field-marshal and first Earl of Kandahar and Waterford, was born in Cawnpore to the Irish commander of the regiment, Lt. Col. Abraham Roberts. Two 2nd Bengal European regiments were raised in 1765 and 1824, both being subsequently disbanded but in 1839 another 2nd regiment was formed.

Five Victoria Crosses were won by soldiers of the 1st regiment and one by a member of the 2nd during the Indian Mutiny. Four of these were awarded at Delhi in 1857, Irish names such as Drummer Ryan, Private Reagan, Patrick Flynn, Corporal Keefe and Private Murphy being prominent among those men recorded as fighting with ‘indescribable fierceness’.

The Munsters’ nickname, the ‘Dirty Shirts’, by which they became popularly and famously known, has been attributed to comments by General Lake at the siege of Bhurtpore in 1805. But it more probably dates from the Indian Mutiny when, because of the heat, men of the Bengal European regiments were reported as fighting in ‘light grey pantaloons and shirt sleeves’. When the British government assumed control over the administration of India in 1861, the Bengal European Regiments were transferred from the East India Company to the Crown.

Soldiers of the Queen

The 1st regiment was re-designated the 101st Royal Bengal Fusiliers, and the 2nd became the 104th Bengal Fusiliers. Presented with new colours, the regiments’ old blood-stained ones were laid up in Winchester Cathedral. After further active service, both regiments were sent to the United Kingdom.

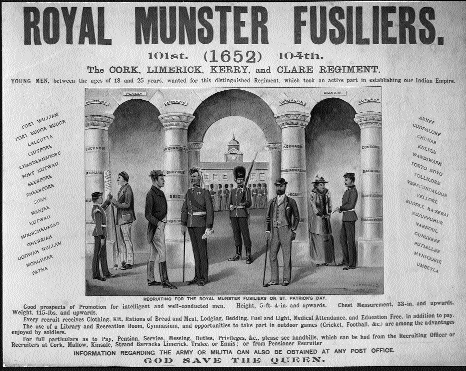

After fundamental army reforms were initiated in 1870 the 101st and 104th regiments were linked together and the Cork, Kerry and Limerick militias affiliated to them. Their recruiting and training depot was located at Tralee and served a catchment area comprising Cork, Clare, Kerry and Limerick. A local identity was thus cultivated. Largely composed of Irishmen, the linking of the regular army regiments with Irish counties and their militias was not as anomalous as it may at first appear. The 101st Regiment left England in 1874 to serve in Malta, Cyprus, Nova Scotia and Bermuda, and the 104th was stationed in Ireland.

In 1881 the 101st and 104th regiments and the militias were merged to form a single regiment—the Royal Munster Fusiliers. The 101st, which was still abroad, became the 1st battalion and the 104th was re-designated the 2nd battalion. The militias became the 3rd, 4th and 5th battalions. The new regiment’s cap badge, a grenade with the royal tiger of Bengal on the ball, preserved the Indian connection. In 1882 the 2nd battalion went to Malta and India, joining the Burma Field Force in 1887. The 1st battalion returned to Britain in 1884 from where it was sent to South Africa on the outbreak of the Boer War.

The Boer War

The anti-recruiting campaign in Ireland reached its climax at the time of the Boer War. Constitutional nationalists and separatists associated the Boers’ fight against the British with their own struggle for home rule or independence, and the 200 soldiers of MacBride’s ‘Irish Brigade’, who fought with the Boers, were duly praised. But the gallantry of soldiers in the Irish regiments serving in South Africa was also acclaimed. There were around 28,358 Irish non-commissioned officers and men in the British army at the time and the 1st and 2nd battalions and the 3rd (militia) battalion Royal Munster Fusiliers saw active service in South Africa.

After the war the 1st battalion embarked for India and the 2nd battalion went home to Ireland where it was presented with new colours at Cork by King Edward on 1 August 1903. It took part in George V’s Coronation Day procession in London in June 1911, and was used in support of the police in Birmingham and Coventry during industrial disturbances in August. In Coventry, rifle butts and fixed bayonets were used to overawe a crowd attempting to raid the battalion’s wagon containing kit, blankets, and ammunition. Soldiers played cricket with the police, were entertained in private houses, given free entry to swimming pools and music halls, and were generally fêted. The police chief, an Irishman whose force contained many of his countrymen, dined with the battalion’s officers, arranged visits to local places of interest, and laid an official report before parliament commending the Munsters’ work during the period of labour unrest. On the outbreak of the First World War, the battalion was sent to France.

The western front

In its first battle of the war at Etreux, 27 August 1914, surrounded and outnumbered eight to one, the entire battalion was killed, wounded or taken prisoner after fierce resistance. When soon afterwards Sir Roger Casement attempted to recruit prisoners of war for an ‘Irish Brigade’ to fight with the German army, he was man-handled and shoved ‘out of the place’ by a Munster Fusilier.

Brought up to strength with new recruits, the battalion sustained further heavy losses. By May 1915 three of its five commanders had been killed and one badly wounded. However, the battalion could still cheer John Redmond, the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, when he visited them at the front in November 1915. One explanation for this loyalty was the soldiers’ respect for their officers and priests. A sergeant-major wrote that ‘the officers share the same hardships as the men, and, in fact, a little more. They are absolutely splendid, every one of them.’ Of Fr. Gleeson, the chaplain, he noted:

He said Mass for us on Christmas Day, actually in the firing line. Where he had his little alter was peppered with bullets. He is a grand priest and knows no fear. He is never finished doing all in his power for everyone, even those who are not of the same religion. …Nothing gives him greater pleasure than saying Mass in the open, in cold and wet, or hearing confessions in some old barn that has been half blown away by German shell fire.

Before going into battle at Rue du Bois on 9 May 1915, when it again suffered fearful casualties, the battalion received the last absolution from Fr Gleeson and sang the Te Deum. Published in the Christmas edition of The Sphere, Mantania’s painting of the incident soon became one of the most famous pictures of the war. When it was reproduced a year later in the Weekly Freeman it was framed and hung on the walls of many private homes, especially in Munster. Private soldiers from Limerick recorded how, during the battle, Fr Gleeson ‘stuck to his post, attending to the wounded and dying Munsters…shells dropping all around him’.

The 1st battalion left Rangoon for England in December 1914, bringing with it the green cloth shamrock badge which had been sewn on to the side of the soldiers’ sun helmets. Reluctant to lose it, approval had been given to place the shamrock under badges on soft forage caps. This practice was unique to the Munsters. The battalion sailed from England and took part in the Gallipoli campaign.

Gallipoli

When it landed from the River Clyde at ‘V’ beach near Sedd-el-Bahr on 25 April 1915, sixteen officers and about 600 other ranks were killed, drowned or wounded. In a private letter, a retired major whose father had been an officer in the 101st Royal Bengal Fusiliers, recalled that

the…part of the landing I experienced was pure butchery and we were at the receiving end. They called it a ‘landing’ but it was hardly even that at the beginning. The dear men were just mown down in scores into a bloody silence as they showed themselves at the Clyde’s open hatches.

After a cold night, packed together on the beach and harried by intermittent sniper fire, the Munsters successfully attacked the Turks against overwhelming odds on the following morning. But the strategy of which the landings formed part was a failure. The battalion was withdrawn and sent to France in 1916. The Munsters’ badly depleted ranks were replenished and the regiments’ numbers were expanded by new recruits and additional battalions raised as part of Kitchener’s ‘new armies’.

Reproduction of Mantania’s painting-Fr Gleeson gives absolution to the 2nd battalion before the battle at Rue du Bois, 9 May 1915. (Kevin Myers)

’.

Expansion

The Irish Parliamentary Party supported Irish involvement in the war and encouraged recruitment into the British Army. Despite an extensive and well organised anti-recruitment campaign by Sinn Féin, 140,000 men enlisted in Ireland. Around 65,000 of these were Catholics, nearly 50,000 of them coming from the southern counties. They included large numbers of Redmondite National Volunteers and nationalists appointed as officers.

The mood of people in southern Ireland at the time is exemplified by a penny song sheet which a woman who had two uncles killed while serving with the Munsters, recalled her mother buying from a ballad singer on the Coal Quay, Cork:

The Munster Fusiliers

Come pass the call ‘round Munster.

Let the notes ring loud and clear.

We want the merchant and the squire,

The peasant and the Peer.

For we mean to whip those Germans,

So away with your paltry affairs

And come join that grand Battalion

Called the Munster Fusiliers

The Kaiser knows each Munster

By the shamrock on his cap

And the famous Bengal tiger

Ever ready for a scrap.

With all his big battalions,

Prussian Guards and Grenadiers,

He feared to face the bayonets

Of the Munster Fusiliers

When marching up through Belgium

Sure we thought of days of old.

The cruel sights that meet your eyes

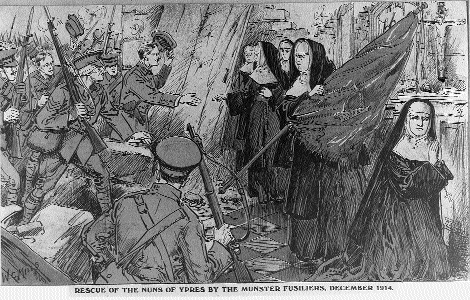

Would make your blood run cold

To see the ruined convents

And the Holy nuns in tears.

By God on high avenge or die

Cried the Munster Fusiliers

God rest our fallen comrades,

May they take their long last sleep

On the fields of France and Flanders.

Sure, we have no cause to weep,

For their deeds will live in history

And the youth of future years

Will read with pride

Of the men who died,

The Munster Fusiliers.

The Munsters raised four new ‘service’ battalions, each of around a thousand men. The 6th and 7th battalions participated in the Suvla Bay landings on the Gallipoli peninsula in 1915, the 6th battalion also taking part in the capture of Jerusalem in 1917. And the 8th and 9th battalions fought with the 16th (Irish) Division on the western front. Rebellion at home threatened to undermine the loyalty of these soldiers, however.

The Easter Rising

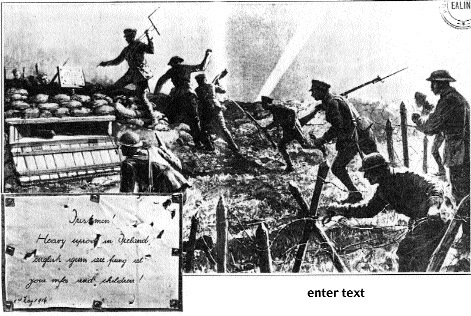

Under the heading ‘Brave Munster Fusiliers: Capture of German Insulting Placards’ The Times reported that within forty-eight hours of the Easter Rising, the Germans used placards to taunt the Munsters who were in trenches opposite them. The Irish troops reportedly ‘responded by singing Irish songs and “Rule Britannia!”’ A raiding party, a number of whom were ‘badly wounded’ crawled across no-mans-land and seized the ‘obnoxious’ placards which they bore back to their own trenches in ‘triumph’.

However, an entry in the 8th Munsters’ war diary for 10 May 1916, simply records that there was some enemy artillery, rifle, grenades and torpedo activity at 1am when Lt. Biggane went out to the enemy sap and found it unoccupied. He brought back two notice boards with the following announcements: ‘Irishmen! Heavy uproar in Ireland; english [sic] guns are firing at your wives and children! 1st May 1916’, and ‘Interesting war-news of April 29th 1916. Kut-el-Aara has been taken by the Turks, and whole english[sic] army therein—13,000 men—taken prisoners’. The Munsters remainedloyal but changing attitudes at home had an impact on enlistment.

Contraction

Because of a decline in voluntary recruitment in Ireland losses could not be made up. When the war ended in November 1918 the Munsters had suffered around 2,800 killed with thousands more wounded and the regiment had been reduced to its two regular battalions, a reserve battalion and two garrison battalions. The service battalions had been gradually disbanded and the survivors absorbed into other units. None the less there was still some enthusiasm for the regiment at home. An officer sent to collect its colours from the depot recalled that his party ‘had a good send off by the people of Tralee. The old ladies were waving flags, and men took off their hats as we marched through with colours flying’. Sinn Féiners on the train sang nationalist songs but assured him, ‘don’t worry. You are our regiment. We have a piquet here to see you are not disturbed’.

Troubled times

Grave of an unknown Munster Fusilier killed c.1916 in the Loos salient, Dud Corner Military Cemetery, Loos

However, the troubled times which followed theend of the war severely tested the loyalty of Irishmen who wereex-soldiers or still serving. Some Munster Fusiliers gave their riflesaway to Sinn Féiners. Ex-Company Sergeant-Major Martin Doyle, from near New Ross, County Wexford, who won the Victoria Cross and Military Medal while serving with the 1st battalion Royal Munster Fusiliers in 1918, joined the IRA in 1920. And ex-Corporal Joseph O’Sullivan from Bantry, who had enlisted in the Munsters in 1915, was one of the assassins of General Sir Henry Wilson in 1922. O’Sullivan had been medically discharged with a ‘very good’ military record after being severely wounded while fighting on the western front. Speaking for both men at their subsequent trial, his co-defendant told the court: ‘We came back from France to find that self-determination had been given to some nations we have never heard of but it had been denied to Ireland.’

Daniel D. Sheehan, an independent nationalist member of parliament and former captain in the Munsters’ 9th battalion, demanded that the right of Irishmen to manage their own affairs be conceded. He wrote of belief in the good faith of England having been ‘shattered into fragments’, and denounced the ‘villainous campaign of cowardly murder, arson, robbery and drunken outrage’ perpetrated by the Black and Tans.

But ex-servicemen were victims of the IRA as well as of the Black and Tans. On his return to Ireland Sinn Féiners gave one Munster Fusilier forty-eight hours to get out. A sign attached to the body of another who had been murdered read ‘Convicted Spy: Penalty Death. All Spies and Traitors beware!’. None the less between January 1919 and December 1921, 20,000 men enlisted in the army in Ireland. Over 1,500 of these were from Cork, which had the highest incidence of IRA executions of ex-servicemen in the regimental district. Unemployment in Ireland almost doubled in 1921, and many rejoined the army because of lack of work. With the creation of the Irish Free State, however, British Army recruitment in southern Ireland came to an end.

Disbandment

At a ceremony in St George’s Hall, Windsor Castle, on 12 June 1922, the king, ‘speaking with emotion’ according to the Daily Sketch, took over the colours of the 1st and 2nd battalions Royal Munster Fusiliers and those of the regular battalions of the other Irish regiments with the following words:

Your colours are the record of valorous deeds in war, and the glorious traditions thereby created…By you and your predecessors these colours have been revered and guarded as a sacred trust…As your king I am proud to accept this trust…Your colours will be treasured, honoured and protected as hallowed memorials of the glorious deeds of brave and loyal regiments.

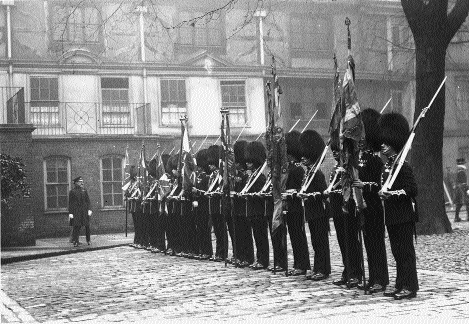

Laying up the colours of the Royal Munster Fusiliers service battalions at the Tower of London, 15 February 1923. (Imperial War Museum)

The king gave a letter of farewell addressed to all ranks to the commanding officer of each battalion. On 31 July 1922 the Royal Munster Fusiliers officially ceased to exist.

The colours of the service and militia battalions were laid up in the Tower of London on 15 February 1923. A memorial tablet to the regiment was erected in Sandhurst Memorial Chapel and a panel was allocated to the regiment on the memorial to the Irish regiments in St Patrick’s Chapel, Westminster Cathedral.

Ex-servicemen were prominent in the ranks of the Free State army during the Irish Civil War and were probably decisive in determining its final outcome. Some sought financial assistance from the Royal Munster Fusiliers’ Old Comrades Association. These included the widow of ex-Company Sergeant Major Martin Doyle VC. William Cosgrove of County Carlow, awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions in Gallipoli on 26 April 1915, died impoverished in 1936. His medal was purchased in 1972 for £2,300. Despite their neglect and Ireland’s official position of neutrality, some ex-Munsters’ chose to again serve in the ranks of the British army during the Second World War.

Tom Dooley is Assistant Professor of Business Studies, Khulna University, Bangladesh.

Further reading:

S. McCance, History of the Royal Munster Fusiliers (Aldershot 1927)

R.G. Harris, The Irish Regiments: A Pictorial History 1683-1987 (Tunbridge Wells 1989).