The Rebellion Papers

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Issue 2 (Summer 1998), The United Irishmen, Volume 6

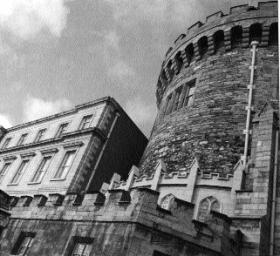

Dublin Castle, seat of the administration. (James Malton, National Library of Ireland)

The collection known as the ‘Rebellion Papers’ in the National Archives, Dublin, has been described as ‘the largest single source for the study of the 1790s’. The material ranges from the early 1790s to 1808, a period which witnessed developments that were to shape modern Ireland: the spread from revolutionary France of republicanism as a political doctrine and the genesis of Irish separatism; the reaffirmation of political Protestantism and its formal expression with the establishment and spread of the Orange Order; the growing challenge of democratic ideas to traditional authority; the increasingly militaristic response of government to the threat posed by political dissension at a time of international crisis, culminating in the open insurrections of 1798 and 1803; and finally the passing of the Act of Union which would ultimately become symbolic of the widening political gulf in Ireland for more than a century to come.

Origin and main features

Some of the material stems from official or semi-official sources: reports and correspondence from military personnel and from paid government informers; papers and letters of some (named) government officials; statements taken from state prisoners (i.e. United Irish suspects and prisoners); lists of such prisoners, and numerous papers found on these at the time of their arrests; and proceedings of courts martial. A greater proportion consists of private letters to Dublin Castle, for the most part by those who would have described themselves as ‘friends of government’—resident gentry, clergymen, local government office-holders, magistrates, and busybodies who took it upon themselves to keep officials in Dublin informed of events and developments in their own areas. The extent of correspondence is remarkable in itself: there are some 4,000 letters from January 1796 through December 1798. In the first six months of 1796 the number averaged thirty-five per month, but for the same period in 1797 this had increased to 179, and in the months of May and June 1798 the number of letters reaching the Castle was 240 and 267 respectively. It is tempting to look at the volume of correspondence to the Castle over these years as some kind of barometer of political or military crisis, but caution must be exercised, not least because of the fortuitous means by which the material has come to survive to this day and in the form in which we now find it in the National Archives in Dublin.

Louis Cullen has traced the location of this collection of papers back to the Irish State Paper Office, Dublin Castle, in 1853, when, according to a report written in 1890, they were stored within two very large chests, officially sealed and displaying the words ‘secret and confidential not to be opened’. When the contents of these chests were sorted by State Paper Office archivists, they filled sixty-eight cartons and it is in this format that they are kept today in the National Archives. The listing of the material was of a standard nature, and these lists (or calendars) consist of five large ledgers. Volumes I and II list what might be described as rebellion papers proper, i.e. material relating to the state prisoners, courts martial, United Irishmen’s papers, etc., mostly dating from 1797 and after. Volumes III, IV and V are calendars primarily of correspondence to the Castle, arranged in chronological order, from 1796 to 1804. The format of the lists is generally as follows: number (of paper); name (and sometimes address) of correspondent; date; brief summary of content.

‘The fact that these unofficial papers should have been retained at all may be ascribed to the diligence of Edward Cooke, Under-Secretary at Dublin Castle from 1795.’ (National Gallery of Ireland)

Edward Cooke’s role

The early eighteenth-century practice by Irish officials of retaining unofficial papers had fallen into abeyance by the 1750s. The fact that these unofficial papers should have been retained at all may be ascribed to the diligence of Edward Cooke, under-secretary at Dublin Castle from 1795. Cooke had first come to Ireland in 1778 as private secretary to the then Chief Secretary, Sir Richard Heron, and had been a member of the administration in Dublin Castle since then, becoming a member of the Irish House of Commons in 1790. He had achieved a position of such influence by the mid-1790s that he was one of those whom Lord Fitzwilliam sacked during the latter’s short and ill-fated viceroyalty in 1795. Reinstated to his post as under-secretary in the military department after Fitzwilliam’s downfall, Cooke’s position in the Castle was enhanced and his importance to government confirmed when in 1796 he was appointed under-secretary in the civil department by the new viceroy, the Earl of Camden. This was a key position in the Irish administration, involving close supervision of the day-to-day business of government, particularly during the frequent absences of the Chief Secretary, Thomas Pelham, due to ill-health.

Cooke was much more than just a civil servant through which intelligence was channelled to the government. The number of letters addressed to him by name, the nature of the information offered and advice sought, all indicate that Cooke’s role was pro-active: many letters are a response to enquiries made by the under-secretary. Cooke’s vigour as an administrator contributed to the extent of the correspondence. Letters to other individuals in, or connected with, the administration (e.g. Chief Secretary Thomas Pelham, or John Lees, Postmaster General) are also to be found among the Papers, indicating the under-secretary’s role in screening correspondence, collecting information and analysing the various strands of intelligence reaching the Castle. The exact nature of Cooke’s political role remains elusive, however, since while many letters written to Cooke remain, much less survives of correspondence written by him. It was not customary at this time either to register or to copy incoming correspondence which was non-official, nor were copies routinely kept of out-going correspondence to private individuals. The result is that, while we have an abundance of views from Cooke’s correspondents, Cooke’s reaction or advice must often be inferred.

The Record Tower, Dublin Castle, formerly the State Paper Office, where the Rebellion Papers were held, until its amalgamation into the National Archives, Bishop Street. (Brigid Fitzgerald)

The State of the Country Papers

The Rebellion Papers also tell us a great deal about the way in which the administrators in the Castle worked, with letters being passed from one official to another in the course of business. In similar manner, there is evidence that many letters were passed by Cooke to others such as Pelham or Camden. Such letters were sometimes retained by these individuals and are to be found now in other collections, e.g. the Pelham Papers, the Home Office Papers, etc.. Even within the Castle itself some of the correspondence became separated from the main collection in Cooke’s office and was lodged in other files. This is the most likely explanation for the fact that at least two other small collections of correspondence to the Castle for this period were subsequently uncovered by archivists and listed separately from the Rebellion Papers, as the ‘State of the Country Papers’, first and second series. The letters in these collections are indistinguishable in origin and purpose from those in the Rebellion Papers and should be regarded as correspondence to Dublin Castle which at some stage became separated from the main body of the collection.

The nature and importance of the correspondence

While the letters deal with a range of issues, ‘law and order’ looms largest. The ongoing war with revolutionary France meant that security, whether against external enemies or against subversion from within, was of prime importance to the government and its supporters. It is perhaps natural that ‘friends of government’ should be concerned with and seek to inform officials about any developments in their locality which they saw as a threat to the status quo.

For this reason in early 1796, and at irregular intervals thereafter, the ‘Armagh troubles’ are the subject of much discussion. In February 1796 the Earl of Gosford described the situation in that county in grave terms:

Of late no night passes that houses are not destroyed and scarce a week that some dreadful murders are not committed. Nothing can exceed the animosity between Protestant and Catholic at this moment in this country.

While Gosford’s letter offers a detailed account of events in Armagh, it can be seen as an apologia for his own rather ambivalent stance and cannot be taken at face value. The Sheriff of Armagh, John Ogle, writing to Cooke from Newry in July, also gives a version of the origins of the Armagh dispute and includes an analysis of the sectarian problem:

The former [Protestants] will not be satisfied with the security and advantage they possess unless they may be allowed to bawl out Protestant Ascendancy, as on the twelfth…and the latter [Catholics] will be found the more disaffected should any untoward event enable them to retaliate.

When, due to increasing concern about the possibility of French invasion, the government decided to sanction the establishment of corps of yeomanry, the manner of raising these becomes a dominant theme in letters to Dublin Castle from all parts of the country. In September 1796, Lt. H.I. Stuart (a member of the Stuart family of Grace Hill, Ballymoney) wrote from his post at Coleraine of some of the difficulties he foresaw with the measure.

In the county of Down I am sure such a measure could very well be carried into effect, but in the county Antrim there actually are not those people who come under the description of yeomen—they are chiefly manufacturers, people who are supported without cultivating so much ground as would enable them to keep a horse in the manner required…A number of infantry could be raised who would in this country do more service than cavalry, where you could scarcely in any direction cross the country for a mile without coming into bogs and swamps.

The raising of a yeomanry corps was enthusiastically greeted in some parts. For example, a meeting to promote the plan at Lismore, County Waterford in October 1796, was described by Sir Richard Musgrave as ‘a numerous assembly’ at which his wholehearted backing of the yeomanry proposal was met by ‘bursts of applause’. Musgrave noted that ‘most of the persons present were papists; which shows how much popularity Grattan and his good coadjutors have acquired among the honest, the sober and industrious papists of Ireland’. In Omagh, County Tyrone, James Buchanan reported an attendance of nearly 2,000 people in a Presbyterian meeting house and commented: ‘The greatest spirit of loyalty and of resistance to the French and Belfast principles were aroused and appeared among them’.

The inhabitants of Belfast, on the other hand, showed less enthusiasm for the government-sponsored corps. Colonel Lucius Barber wrote in January 1797 that yeomanry corps had been got together consisting of about 150, ‘such as they are’ and that ‘much intrigue and interest was employed to collect even that number’. There were problems reported also elsewhere: John Bell wrote about the efforts which he and other ‘well-affected’ people of County Longford were making to raise a cavalry corps:

You cannot think what a party is made against us, and every means devised to deter men from enrolling in any association that government is to have anything to do with. These have distinguished themselves by cropping and hold meetings almost every night in Granard; I am convinced their plans are hostile to King and Constitution; there seems to be a junction between the Presbyterians and the Roman Catholics.

The spread of ‘disaffection’ and the activities of seditious groups, particularly the United Irishmen, is a constant theme. Thomas Knox, a regular correspondent, writes to government in July 1996 about the area around Dungannon:

It is a folly to shut our eyes to the situation of the country. It is teeming with treason and what is worse, treason methodized. It will surely be wisdom to oppose system to system. If it be true that the conspirators are formed into companies and ready to rise at the shortest notice, ought we not to take a lesson from them, ascertain our strength and have a rallying point in each district. If they are up before us we are lost.

Describing the ‘changed nature of the county’ (near Coleraine), John Richardson writes in October 1796 that ‘hardly a man can be found in the rank of a farmer, manufacturer, and labourer even to say he is willing to take the oath of allegiance’. The north-west was not, it seems, so disaffected: at the same time Thomas Conolly reported the willingness of his tenants near Derry to form yeomanry corps. Richardson was aware of the significance of Belfast: ‘it is apparent that the disposition to rebellion is more or less in proportion to the distance from that seat of mischief’. He identified trade and lines of communication with Belfast as a key factor in the spread of the United Irishmen. Conolly’s confidence regarding the loyalty of his tenants was soon to be shaken. On 19 November 1796 he reported that the people on his estate were ‘as rebellious and wicked as in any part of the north’.

Many of the letters are concerned not only with the threat of sedition but also with prescriptions for countering it. In April 1797, William Lambert reported from Edenderry, County Offaly, that night-time robberies of arms were causing alarm to the local magistrates particularly since they had failed to obtain any convictions. The writer suggested that the authorities should respond to the threat by burning the houses of suspects.

The measure…seems severe, but if something severe is not adopted sufficient to stop the progress of these villains, who are increasing their numbers and acquiring firearms every night, every house in the country must fall a sacrifice to them immediately and very soon after the towns.

While many of the letters were aimed at persuading government of the need for action, others provide insights into the people’s political consciousness:

I have often asked men who I knew to be disloyal, what all this outrage and combination by oaths was intended for, and they all answer ‘to obtain a reform in Parliament’, [and] at the same time declare most solemnly that they are steady in their attachment to the King, and that they do not wish for the French to make a landing among us.

Thus reported Edward Moore of Aughnacloy in March 1797 in a letter to John Lees. The same letter reveals a more mundane grievance:

In the different parts of the country where I have an opportunity of hearing the minds of the people I find that the salt tax, and not taxing absentees, is loudly complained of. The poor family (say they) never sit down to a meal of potatoes, that this tax is most aggravating, while the great man carries off the wealth of the country and does not assist in the expenses of the kingdom where his property is protected.

The radical politics and democratic sympathies of northerners had repercussions for farmers and other traders from Ulster. John Pollock wrote from Navan in October 1796 of his efforts to prevent the people of County Meath ‘being abused by the factious and traitorous attempts’ of ‘emissaries of the North’. He explained:

In Kells fair yesterday there were few northern buyers and no man there could purchase stock unless he could get a resident gentleman here to endorse his bill. Their conduct and their politics were execrated and the stagnation which took place, owing to their not being credited for a shilling, has powerfully turned the minds of the people here against them.

Correspondents routinely reported to government anything of a political nature which occurred in their locality. The Rebellion Papers can therefore be an important source for the local historian. They are often full of vivid detail regarding local people and events. On the eve of insurrection, for example, a letter from Kells describes the ceremonial laying of the foundation stone for the new Catholic church in the town by the Earl of Bective in April 1798. Such glimpses into more mundane aspects of life in Ireland at this time have their own attraction. It is sometimes possible, where a resident is a regular correspondent, to trace significant events for a particular area over a number of years. However, on this point, caution should be exercised in relation to their reliability and partiality as witnesses.

Dublin Castle’s loyal correspondents

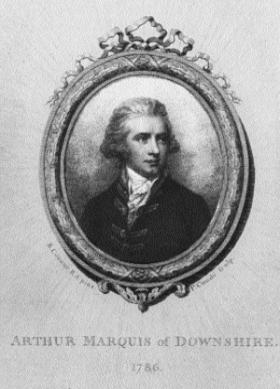

The Marquis of Downshire, the most notable of Cooke’s regular correspondents. (National Portrait Gallery, London)

The most notable of the regular correspondents to Cooke was the Marquis of Downshire. In the series of letters between them Cooke’s role can most clearly be seen, in maintaining and reinforcing a communication network with loyalists in the counties perceived to be at risk from sedition. Downshire’s letters are certainly some of the most entertaining, with his arrogant frankness only too obvious.

Writing in November 1796, for example, Downshire voiced his opinion of the Presbyterian clergy:

The Presbyterian ministers are unquestionably the great encouragers and promoters of sedition, though as yet they have been cunning enough to keep their necks out of the halter. I think it hard that the rascals should enjoy the King’s bounty to enable them to distress and destroy his government. It would be a good time to reduce the [Regium] Donum to what it was in King William’s time if not to take it away entirely.

Downshire’s pre-eminent position of influence is clear in a letter on the issue of raising yeomanry corps, when he warns the government:

Pray do not be too easy in admitting offers [to raise corps] or so undecided with your friends, or if I am to have anything to do in this county pray do not let others act without my knowledge.

Some months later Downshire’s plans for having County Down proclaimed ‘disturbed’ (and therefore made subject to the draconian regime of the insurrection act) met with some legal misgivings on the part of the Privy Council in Dublin. Downshire’s reaction in a letter to Cooke was typically forthright:

Let them [the members of the Privy Council] be assured that the Justices [of the Peace] who live in the county, who act without salary, fee or reward, but at the hazard of their lives and properties, feel as much difficulty and as much repugnance in putting a harsh law in force, as anyone who sits at the Board.

His emphasis on the role of the resident gentry in the north, the front-line of loyalist defences against the United Irishmen, was a clever attempt to apply pressure:

I wish you and your privy council were obliged to live here for three weeks, you would all by acclamation and I daresay in the utmost haste and irregularity and without attending to precise words or form, be for proclaiming not only this county but Belfast and the province of Ulster…If there is a rebellion and His Majesty’s loyal subjects murdered, let it be on your heads that are comfortably sitting in your closets in Dublin and pretending to decide without knowing how bad we who reside in the country know the state of it to be. Thus, my dear Cooke, I have stated my real sentiments. I am no alarmist, I am an enemy to terror. I love my King and my country and will do what I think my duty, though inconvenient to myself or disagreeable to others.

Taking the correspondence as a whole, those who wrote to the Castle were generally those who identified themselves with the government, supported its efforts and sought to uphold its authority: the ‘loyal’ whose interests the Camden administration protected. As well as those genuinely concerned with their lives and properties, the correspondents also included some whose motives were more self-serving, for example, those who wished to ingratiate themselves with the administration, or who sought to defend themselves from criticism from another quarter. It is important to note that the correspondence is derived primarily from one section of the polity: letters from ‘liberal’ gentry or magistrates are rare. Political opponents of the government tended not to write to the Castle and the result is a rather lop-sided collection of information, with an overabundance of evidence from loyalists but only occasional contributions from liberals and others who favoured conciliation of the ‘disaffected’ by moderate reform. Such contributions usually take the form of a short, and fairly frank, exchange of views between Cooke (or Pelham) and a local political opponent, generally prompted by a local incident of concern to the latter. It is this characteristic—the absence of a sustained commentary on events by the political opposition to Camden’s government—which is perhaps the most glaring limitation in the collection and it must be taken into consideration by any researcher.

Conclusions

The archive is a treasury of information for researchers of this period, but one which requires cautious use. In particular one should investigate the credentials of each author, as far as possible, through the usual directories. The background, social status, religious/political persuasion of the writer should be taken into consideration in assessing the value of his evidence. Nothing should be taken at face value in these letters: even the language used is open to interpretation. For example, what is really meant by the description ‘active magistrate’? Reports to the Castle must be viewed as part of a fuller picture of local events and should be considered in the context of wider social and political developments at this time. However, all of this is grist to the mill for historians.

Deirdre Lindsay teaches history at St Mary’s College, Derry.

Further reading:

D. Lindsay, ‘The Rebellion Papers’ in the Federation of Ulster Local Studies’ The Turbulent Decade: Ulster in the 1790s (Belfast 1997).

L.M. Cullen, ‘Politics and Rebellion: Wicklow in the 1790s’ in Hannigan and Nowlan (eds.), Wicklow: History and Society (Dublin 1994).