‘The Moderns’ reassessed

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 5 (Sept/Oct 2011), Volume 19

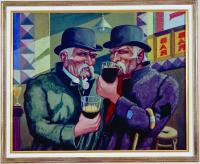

he twins by Harry Kernoff—one of the well-chosen paintings in the exhibition. (Private collection)

Irrelevant non-Irish artists

As the subtitle to this exhibition—‘The Arts in Ireland from the 1900s to the 1970s’—inadvertently makes clear,

What, precisely, was the influence of Shaw’s snaps.

this isn’t about Modernism in Ireland but is rather a loose, lopsided history of twentieth-century Irish art (including much post-Modernist work) which actually contains a wide range of artwork that S.B. Kennedy in his much more rigorous book Irish art and Modernism 1880–1950 would have labelled ‘The Academic Tradition’. It also contains much work by non-Irish artists on the pretence that they influenced the Irish ones. In a room devoted to the White Stag Group, for instance, we have the American novelist J.P. Donleavy’s Don’t Mind Me I’m From the New World. The date given is c. 1940, which would make Donleavy roughly fourteen years of age. The work itself is a commercialised blue nude in imitation of the School of Paris. Donleavy is primarily a novelist who didn’t take Irish citizenship until 1967. What on earth is he doing here? Does anyone seriously think that a fourteen-year-old American boy’s daub has any relationship to Modernist Irish art? Ironically, one major aspect of the impact of the White Stag Group, most of whom weren’t Irish, is virtually ignored: their attempt to deal with World War II and the threat of global warfare.

In the ‘Surrealist Influences’ room we have a Giorgio de Chirico, but as it is dated c. 1960 it obviously had no influence on the other work in the room, which is from the ’40s and ’50s. In the ‘Tony O’Malley and the St Ives School’ room we have three English artists, including a Peter Lanyon (O’Malley knew the artist) which bears no obvious relevance to O’Malley’s work. There is also a Patrick Heron but one that relates much more to William Scott than it does to O’Malley, and for some incomprehensible reason we have a William Tucker sculpture, and one that is in his very early figurative manner as opposed to the later stripped-back abstractions that made his reputation.

or Casement’s supposedly political take on ethnographic images? How does any of this material contextualise Irish art? (Shaw Estate, LSE/National Trust; Casement Collection/National Photographic Archive)

Film and photography

The IMMA claims that film is central to the visual arts canon; I quite agree—but not in the way that the IMMA seems to think. Its evidence primarily consists of Robert J. Flaherty’s documentary on Aran fishermen, but it is seemingly oblivious to the fact that this is romantic fakery—it’s certainly not Modernist. It also shows Becket’s Film, which even the catalogue essay by Theo Dorgan acknowledges as ‘hopelessly dated now’ but which is also privileged by a separate essay on the film by David Lloyd that tries to persuade us that Becket was heavily influenced by the Belgian painter Van de Velde. So we are being told that a dated film made by an Irishman who spent most of his life in France, and who made the film in France seemingly under the influence of a Belgian painter, is somehow central to the visual arts in Ireland? Let’s be honest—the only reason Becket is co-opted is for the same reason that everyone from Kokoschka and Giacometti to Freud are co-opted: cultural cachet.

We are told that Irish photography should be considered a mainstream practice (though what this has to do with Modernism is another matter!), yet what we are presented with is a mixture of early photojournalism from the Irish Independent, private snaps from George Bernard Shaw, supposed ‘documentary’ images from Roger Casement and highly commercialised fare like John Hinde’s postcards, but—noticeably—virtually no ‘art’ photography.

still from Samuel Becket’s Film, which even the catalogue essay by Theo Dorgan acknowledges is ‘hopelessly dated now’. (Barney Rossett)

Northern Ireland ignored

The section on Modernist Irish architecture ignores Northern Ireland in its entirety (even pre-partition!). So there’s nothing on the Modernist buildings of William Clough Ellis, or the Modernist homes on Belfast’s Malone Road. This is consistent with one of the major manipulations of art history in this exhibition: Northern Irish art is either ignored or downplayed. Aidan Dunne, with quite breathtaking effrontery, dismisses Northern artists of the ’50s in a few sentences, despite its being well known that it was Northerners in the shape of Dillon, Campbell, Armstrong and Co. who provided much of the motive force during that decade.

Rocky landscape with trees (c. 1925) by Mary Swanzy—one of Ireland’s most underrated painters. (Pyms Gallery, London)

Dillon, just to give one example, is wrongly described as ‘alternating between building work in London and painting in Ireland’, as if he were some part-time bit-part player, whereas he always had a studio in London, even in the ’30s, and made a point of keeping himself abreast of the London galleries.

This anti-Northern bias reaches epidemic proportions when we approach the ’70s and the Troubles. Believe it or not, this museum pretends that artists’ responses to the Troubles are summed up by some straightforward images by Bobbie Ballagh, an atypical sculpture by Oisín Kelly and a small raft of foreigners, especially Americans. Not a single Northern socio-political artist is included, even though there are over 50 of them, including at least eight key players; to add insult to injury, Brian O’Doherty, a Southerner domiciled in New York since the ’50s who belonged to the Conceptual Movement there, and who changed his name to Patrick Ireland, supposedly because he believed that the British should get out of the North, is given pride of place. Did he bear witness to the North like the Northern Irish artists?

Lack of literary contextualisation

And then we come to what passes for the literary contextualisation: just as the IMMA seems to think that curating means putting whatever you can get your hands on onto the walls, it also seems to think that contextualisation means putting an oddball selection of books in cases; and instead of discussing the possible relationships of these works to the art on the walls, one simply stays silent.

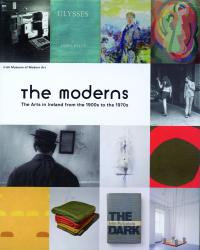

The exhibition’s massive catalogue (available only after it had finished)—while there are footnotes to the essays, there is no bibliography, the index only covers artists and illustrations (which are not cross-referenced to page numbers), there is no chronology and, despite three editors, one copy-editor, four editorial assistants and two proof-readers, a number of the essays are written in turgid, often non-grammatical English and there are many, many typos. (IMMA)

Brian McAvera is an Irish playwright, art critic, curator and art historian.

Further reading:D.M. Earle, Recovering Modernism (Surrey, 2009).E. Juncosa and C. Kennedy (eds), The Moderns: the arts in Ireland from the 1900s to the 1970s (Dublin, 2011).S.B. Kennedy, Irish art and Modernism 1880–1950 (Belfast, 1991).B. McAvera, Icons of the North (Belfast, 2006).