The Men of No Popery: the Origins of the Orange Order

Published in 18th-19th Century Social Perspectives, 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 3 (Autumn 1995), Penal Laws, The United Irishmen, Volume 3 We’ll fight to the last in the honest old cause,

We’ll fight to the last in the honest old cause,

And guard our religion, our freedom and laws.

We’ll fight for our country, our king and his crown,

And make all the traitors and croppies lie down.

As the television documentaries, radio programmes and newspaper features marking the bicentennary of the French revolution rolled on through 1989, no one can have been left in any doubt where the pundits stood. The revolution is no longer considered to have been a good thing. According to current orthodoxies the costs of the Terror outweighed the benefits of the Rights of Man and Citizen (which would, in any event, have been achieved without the bloodshed). These views are very different from those enshrined in the ‘Great Tradition’ of historiography which celebrated the revolution for its contribution not only to the progress of French civilisation but to the world.

Study of counter-revolution in fashion

One consequence of the partial eclipse of the ‘Great Tradition’ is the increasingly fashionable study of counter-revolution. A similar trajectory is traceable in English historiography. Over twenty-five years ago E.P. Thompson added a postscript to the paperback edition of his classic The Making of the English Working Class in which he answered the book’s many critics. Rebutting his detractors with characteristic gusto, he nonetheless accepted the objection that he had paid insufficient attention to ‘the flag-saluting, foreigner-hating, peer-respecting’ side of the plebeian mind. Popular xenophobia, deference and loyalism, Thompson conceded, were too little examined and less understood. That was in 1968. Today the study of militant loyalism and ‘vulgar conservativism’ in the 1790s is a booming cottage industry. Thompson’s radical reformers have been overshadowed by Linda Colley’s flag-saluting Britons.

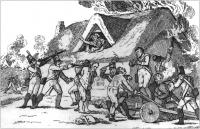

Irish loyalists under siege, by Cruikshank, from Maxwell’s Irish Rebellion.(1845)

Irish historians have not followed English and French trends. The proceedings of two major conferences, held in 1989 and 1991, to mark the bicentennaries of the impact of the French revolution on Ireland and the foundation of the Society of United Irishmen, have now been published, and undoubtedly the two hundredth anniversary of the 1798 rebellion will occasion further gatherings and volumes. The foundation of the Orange Order in September 1795 has not attracted the same level of scholarly attention. This may be explained by the sheer scale of the radical movement. The United Irishmen mounted a more formidable challenge to the government than either its English or Scottish counterparts, while inversely Irish popular loyalism, mobilised by the Orange Societies, never achieved the nation-wide support enjoyed by the British ‘church and king’ associations. Yet the Orange Order survives to this day, it played a prominent and controversial role in the Irish counter-revolution and it offers a fascinating example of the dynamics of popular politicisation in the late eighteenth century.

Orangeism conformed to international patterns. As well as stimulating radical revivals across Europe and the British Isles, the French revolution polarised politics everywhere. In each country the revivified radical movements confronted conservative and royalist anti-’Jacobin’ crusades. Sir Richard Musgrave, the loyalist historian of the rebellion, and himself an Orangeman, made the point: ‘In the year 1792 when the dissemination of treason and the formation of seditious clubs in London threatened the immediate destruction of the constitution…loyal societies checked the progress and baneful effects of their doctrines. The institution of the Orangemen did not differ from them in the smallest degree’. It is true that in its devotion to the Protestant constitution, church and crown, as in its opposition to French principles, domestic ‘Jacobinism’, Thomas Paine and all his works, Orangeism paralleled British loyalist movements; but its roots lay deep in the Ulster countryside.

Lurid cartoon entitled ‘Peep O’ Day Boys’, from Daly’s Ireland in’98(1888). The caption is probably inacur-rate

because the villains are in uniform.

Armagh: crucible of sectarian conflict

The Orange Order was forged in the crucible of sectarian conflict in County Armagh. The most densely populated county in the country, Armagh was a microcosm of late eighteenth-century Ireland. Each of the three major religious denominations were represented there in roughly equal proportions, with a Catholic majority in the poorer south, an Episcopalian majority in the north, and Presbyterians most numerous across the centre. Each confessional group had a corresponding ethnic identity, Irish-Catholic, Scots-Presbyterian and English-Episcopalian, and each was present to some degree in all areas of the county. That finely balanced religious demography itself helps to account for the persistent sectarian tensions. Patterns of settlement, dating back to the seventeenth-century plantation, created ‘cultural frontiers’, flash points of territorial dispute and inter-communal strife. All of these elements combined in the circumstances surrounding the brutal killing of the Protestant schoolmaster, Alexander Barclay, by the Catholic Defenders at Forkhill in 1791. Part of an ‘improving’ project, Barclay’s school taught through the medium of English and intruded into a predominantly Catholic, Irish-speaking, area.

Because of their numbers Catholics appeared more threatening to their Protestant neighbours, than in counties such as Antrim or Down where they were a clear minority. The Presbyterian farmers of Antrim and Down who later embraced the union of Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter in the United Irishmen felt safe to do so; in Armagh it was different. When the masonic lodges of Antrim, Down, Derry and Tyrone endorsed parliamentary reform in the winter of 1792-3, the Armagh masons condemned them. Reform—or innovation as they denounced it—touched the simultaneous campaign for Catholic relief too closely for comfort.

Land hunger?

An explosive religious geography reacted upon an unstable social structure and local economy. The formation of Orange Lodge No.1. followed a violent clash between armed Protestant bands and Defenders at a cross-road hamlet, named the Diamond, near the village of Loughall. Up to thirty Defenders were killed that ‘running Monday’, 21 September 1795, while none of the surviving accounts record any fatalities on the Protestant side. The ‘Battle of the Diamond’ ranks as one of the more bloody encounters in a sequence of disturbances between the Protestant Peep O’ Day Boys and Defenders stretching back to the mid 1780s. That endemic unrest used to be explained by land hunger. Following the repeal of penal laws restricting Catholic access to landed property in 1778 and 1782, Catholic competition for leases intensified, driving up prices and provoking Protestant resentment. Then in 1793 the Catholic relief act enfranchised forty-shilling freeholders in the counties, thus increasing the political value of Catholic tenants to landlords. The ‘land hunger’ explanation of the Armagh troubles has now been superseded by more sophisticated theories, which stress the destablising effects of modernisation and the political dimensions of the Peep O’ Day backlash; but many witnesses to these events linked land competition to sectarian rivalry. Rather than simply discounting the land issue as the cause of the disturbances, it needs to be integrated with newer theories as one cause among several.

‘A hotbed of cash’

In fact the economic importance of land was diminishing during this period. Late eighteenth-century Armagh experienced rapid social change generated by its thriving linen industry. Much of the linen-led commercial and manufacturing expansion of the Irish economy at this time centred on Ulster’s ‘linen triangle’, an area comprising west County Down, north Armagh and mid Tyrone. Linen, produced for sale in the market place by piece-working, wage-earning journeymen weavers, transformed rural society. By the 1790s in some parts of the county agriculture had become an adjunct to the textile industry. Land supplemented income from spinning, weaving and bleaching rather than the reverse. Armagh, noted a contemporary observer, ‘is a hotbed of cash’. Inevitably the scale and pace of modernisation loosened the deference-based social controls on which the ‘natural leadership’ of the gentry had traditionally rested. Apprentices and young journeymen who ‘got the handling of cash’ before they knew the value of it, enjoyed an independence of action absent from the forelock-tugging dependency culture of landed society.

Whereas Catholic competition in the land market allegedly drove up the price of leases, Catholic weavers competing in the labour market aroused Protestant hostility by allegedly depressing wage rates. Certainly, substantial Catholic participation in the linen boom is not in doubt. Prominent Catholic radicals, such as Luke Teeling in Lisburn and Bernard Coile in Lurgan, were wealthy linen merchants. The brother of the Armagh priest, Defender and United Irishman, James Coigly, employed up to a hundred ‘hands’ in the county. From the viewpoint of Protestant Ascendancy the Catholic menace included a threat to the livelihoods of Protestant weavers. During the 1780s, Peep O’ Day Boys raiding Catholic homes (which were also their workplaces) in search of illegally held arms, smashed domestic looms whenever they came across them. Again, the wholesale ‘wrecking’ of Catholic cottages by Orangemen in the winter of 1795-6 included the destruction of looms, webs and yarn. The break-down of traditional social control lurched into sectarian economic warfare.

Lt. Colonel William Blacker, from the Dublin University Magazine (1841).

The right to bear arms

Rapid economic change, population pressure and religious geography combined to produce a particularly volatile situation in late eighteenth-century Armagh; the disturbances, however, had a political detonator. Under the penal laws Catholics were denied the right to bear firearms—a proscription which had symbolic and political in addition to practical significance. In an age of citizens’ militias and deep distrust of standing armies, the right of the people to bear arms guaranteed their liberty and property. That at least was the theory. The Irish Volunteers, first formed in Ulster in 1778, embodied classical republican and Whig ideas of armed citizenship, public virtue and legitimate resistance to tyranny. A few years later the right to bear arms received ratification in the written constitution of the new American republic. Thus in the mid 1780s when certain Volunteer companies in Ulster, Dublin and elsewhere admitted Catholics to their ranks, they unilaterally, and illegally, admitted them to fuller citizenship. According to another report, at about the same time the Armagh grandee Lord Gosford armed local Catholics for the less exalted purpose of protecting his orchards from pilfering!

Arms raids were political. The disarming of Catholics in County Armagh amounted to a spontaneous and unilateral attempt by lower-class Protestants to reaffirm Protestant Ascendancy by re-enforcing the penal laws. The Defenders, as the name indicates, began as Catholic bands formed to defend themselves from attack. But, as the movement became proactive and politicised and spread into south Ulster and the midlands, its standard tactic of raiding gentry houses for firearms echoed the original Peep O’ Day Boy campaign, and in the context of the penal laws that tactic was likewise charged with political symbolism. In part arms raids represented an assertion by lower-class Catholics to equal status under the law.

Catholics ‘unfit for liberty’

At a local level the Peep O’ Day Boys tried to maintain a system of privilege built upon religious discrimination. Yet in the eighteenth century popular anti-Catholicism could be a protean, Janus-faced force. Although it fed on the sort of vulgar prejudices concerning superstition and priestcraft so deftly parodied in the writing of Wolfe Tone, and although it could degenerate into the kind of hysterical bigotry personified by Sir Richard Musgrave, it had a positive side. To republicans and Whigs, from John Milton in the 1650s to William Drennan, Volunteer and future United Irishman, in the 1780s, Catholics were justly excluded from the constitution on the grounds that toleration could not safely be extended to the intolerant, nor liberty to its enemies. Those antipathies, historically rooted in Whig myths of the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688 and Irish Protestant folk memories of the 1641 rebellion and of their deliverance from popish tyranny by William of Orange at the Boyne in 1690, were sustained by contemporary perceptions of the despotic Catholic monarchy of France. Catholics, wrote Drennan, were ‘unfit for liberty’. Alongside its popular pedigree, the ‘religion, freedom and laws’ celebrated by the Peep O’ Day Boys’ successor movement, the Orange Order, had a radical and subversive potential which troubled the men of property and the government from the start.

Volunteers and Freemasons

While some Volunteer companies recruited Catholics, others remained aggressively Protestant. The Volunteers who clashed with Defenders in Armagh in 1788, or at Rathfriland, County Down, in 1792, were denounced as little more than Peep O’ Day Boys in uniform. The societies of United Irishmen, established at Belfast and Dublin in 1791, were composed of veteran Volunteers; so too were the first Orange lodges. The decisive Protestant victory at the battle of the Diamond has been attributed to superior firepower, occupation of the high ground, and ‘old Volunteer discipline’. However, the shared institutional ancestry of the Orange and United societies in volunteering and, as we shall see, Freemasonry, is not as mysterious as it might at first appear.

As a form of participation in public life the volunteering experience raised levels of political awareness, but it did not predetermine the content of politicisation. In a way the mere act of associating was in itself just as important as the politics of a particular company. It is no accident that Freemasonry underwent one of its most rapid surges of expansion during the heyday of volunteering, or that it occurred above all in the Volunteer heartlands of Ulster and Dublin. Indeed in several cases Masonic lodges and Volunteer companies merged. Lodges and companies, with their regalia and uniforms, answered largely the same social and recreational demands, and the number of associations in the north testifies to the density and richness of popular culture in Ulster. By 1804 there were forty-three recognised or ‘warranted’ Masonic lodges in Armagh, ninety-two in neighbouring Tyrone and fifty-six in County Down. Masonic secrecy applied only to the internal ritual and business of the craft, not to membership. For example, in October 1784 a Masonic funeral held at Loughall—the site of the original Defender-Peep O’ Day Boy feud—included 1,000 Volunteers and ‘300 Masons in regular procession’. Unsurprisingly such a common style of association provided others, sometimes Masons themselves, with a ready-made model.

The fledgling Orange Order (and the Defenders) borrowed wholesale from Masonic practice and terminology. Orange ‘lodges’, ‘masters’, ‘grand masters’, ‘oaths’, ‘signs’, ‘degrees’, ‘warrants’ and ‘brethren’ all have a clear Masonic lineage. The ubiquity of masonry impressed contemporaries. Sketching in the background to the Battle of the Diamond Mugrave alleged that ‘in the year 1795, the Romanists, who assumed the name of masons, used frequently to assemble in the neighbourhood of Loughall, Charlemont, Richhill, Portadown, Lurgan… and robbed the Protestants of their arms’. On 18 September, three days before the battle, a local gentleman informed the Dublin government that ‘the Protestants who call themselves Freemasons go in lodges and armed’, while forty years later a witness before a parliamentary inquiry recalled that the first Orangemen had employed secrecy ‘to afford protection, if they could, to those who refused to join the United Irishmen; for every act of intimidation was used, and the fondness of the people for associating together, their attachment to Freemasonry, and all those private associations, gave a particular zest to this mode of keeping them to their allegiance’.’James Wilson and James Sloan, who along with ‘Diamond’ Dan Winter, issued the first Orange lodge warrants from Sloan’s Loughall inn, were masons.

The ‘fondness of the people for associating together’, for joining, oath-taking and ‘secret’ collecting, also helps to explain the apparently baffling phenomenon of Orange and Masonic lodges defecting to the United Irishmen and vice versa. These crossovers, which can be accounted for at one level by local political pressures, intimidation and bandwaggoning, were at the very minimum facilitated by the popular ‘fondness’ for joining, belonging and secrecy.

Lower class origins

Despite its militant loyalism and anti-revolutionary ideology, there are remarkable parallels between the early Orange lodges and the Defender-United Irish alliance that had emerged by 1795. Both were popular movements; both had antecedents in Freemasonry and Volunteering; both thrived in the divided, densely textured, modernising society and economy of Ulster. The first of these similarities concerned the government and its supporters most. Dan Winter was a publican and the first lodge masters included tailors, ‘linen inspectors’ and inn keepers. One early lodge, no.7, met in a disused lime kiln, other lodges, echoing ‘hedge’ or ‘unwarranted’ masonry, were known as ‘hedgers’ or ‘ditchers’ from their practice of assembling ‘behind hedges or in dry ditches’. Later apologists rather implausibly deny any connection between the Peep O’ Day Boys and the first Orangemen or, even less plausibly, between the Orangemen and the mass ‘wrecking’ of Catholic cottages in Armagh in the months following the Diamond; all of them, however, acknowledge the movements lower class origins. As one sympathetic, but socially ‘respectable’ chronicler of these years put it, Protestant farmers and linen manufacturers, all ‘humble men…decided to have a system of their own creation, and to control it themselves…an organisation formed and fashioned by their own hands, in harmony with their own ideas, and outside the control of landed proprietors, agents, bailiffs, baronial constables, and all the rest’.

Gentry take-over

Gentry take-over

Predictably, that robust spirit of independence in turn excited the ‘decided antagonism of some of the gentry’. Local gentry families, such as the Blackers and the Verners, were involved in the Orange Order within weeks of its formation and the men of property effected a virtual take-over within about eighteen months, a process culminating in the establishment of a Grand National Lodge boasting several peers and prominent Protestant ultras, in Dublin in 1798. Nevertheless, Orangeism began as a popular initiative. The gentry assumed leadership as a means of reasserting control over a volatile tenantry. Generals Lake and Knox grudgingly harnessed the Orangemen as a counter-insurgency force during a period of crisis. But many magistrates remained distrustful. From the outset Orangeism had a respectablility problem.

The county elites and the government moved quickly to co-opt a movement, denounced by Lord Gosford as a ‘lawless banditti’, because it proliferated at such an astonishing rate. Some 2,000 Orangemen marched at the first 12 July commemoration at Lurgan-Portadown in 1796; estimates for the 1797 procession, reviewed by General Lake, run from 10 to 30,000. By 1798 nation-wide membership may have risen to 80,000, many of whom enrolled in the government sponsored Yeomanry. According to the Authorised Version: ‘the speed with which Orangeism spread proves its adaptability to the wants of loyal men in the period’. In Musgrave’s view lower-class Protestants of the established church were ‘actuated by an invincible attachment to their king and country’. Certainly, the totemic popular appeal of ‘loyalty’ and of the blessings of the ‘Protestant constitution’—the ‘great palladium of our liberties’—must not be underestimated. But Orangeism’s greatest appeal was defensive and reactionary, the maintenance of ‘Protestant Ascendancy’ against the Catholic and republican challenge: Croppies lie down!

Ireland’s unstable sectarian landscape accounts for both the vitality and the weakness of early Orangeism. Like Orangeism, popular loyalism in Britain proudly proclaimed its Protestant character; unlike Orangeism the British associations’ Protestantism reflected the religious affiliation of the majority of their countrymen. In Ireland inter-denominational strife and the size of the Catholic ‘threat’ drove thousands of lower-class Protestants into the Orange ranks. However, the same sectarian arithmetic permanently limited the movement’s popular base. Still, the numbers were too impressive for a government confronted by a serious revolutionary challenge to ignore. Many an Orange Yeoman saw action in 1798.

Exclusively Protestant, the Orange Order was not, in its own view, sectarian. Its brand of Protestantism and anti-Catholicism (or, strictly speaking, anti-popery) was ostensibly political. Protestantism stood for liberty. All Protestants, whatever their doctrinal opinions were welcome to join the order, although in practice Episcopalians outnumbered Presbyterians. ‘Popery’ stood for tyranny and a ‘disloyal’ allegiance to a foreign prince; Catholics per se were entitled to their religious beliefs. Not that that theory prevented the United Irishmen from inventing an ‘Orange extermination oath’, or Catholics from believing it. Nor did refugees from the Armagh ‘wreckings’ harbour any doubts about the violent sectarianism of the Orangemen.

The gentry take-over of the Order in 1796-7 and Orangeism’s counter-revolutionary ideology seem to fit perfectly the Marxist interpretation of it as an instrument of class rule. That interpretation treats Orangeism, and sectarianism generally, as a variety of ‘false consciousness’, which divides the lower classes and side-tracks them from the pursuit of their ‘objective’ interests. General Knox, it is true, deliberately encouraged the Orangemen in their feud with the United Irishmen in Tyrone, but on balance the manipulation /false consciousness thesis (which not all Marxists would subscribe to anyway) is patronising and too pat. Crucially, it fails to appreciate the self-generating capacity of popular loyalism. In Musgrave’s words, rallying ‘round the altar and throne, which were in imminent danger [the first Orangemen] united and stood forward…unsupported by the great and powerful.’ The threat which Musgrave identified came from ‘croppies’, democrats and levellers. But to the government the original lower class Orangemen also represented at least a potential threat. The men of property hijacked the movement in order to contain it

Jim Smyth is a fellow at Robinson College, Cambridge.

Further reading:

The formation of the Orange Order 1795-1798: the edited papers of Colonel William Blacker and Colonel Robert H. Wallace (Belfast 1994).

D.W. Miller (ed.), Peep O’ Day Boys and Defenders: selected documents on the County Armagh disturbances 1784-1796 (Belfast 1990).

D.W. Miller, ‘The Armagh troubles 1785-1795’ in S. Clark and J.S. Donnelly (eds.), Irish peasants, violence and political unrest, 1780-1914 (Wisconsin 1983).

H. Senior, Orangeism in Ireland and Britain 1795-1836 (London 1966).