The Mallory Mount Everest expedition of 1924: an Irish perspective

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 5 (Sept/Oct 2011), Volume 19

Members of the Norton/Mallory expedition of 1924. Hingston is standing, second left. (The fight for Everest, 1924, E.F. Norton)

Western interest in Mount Everest began in 1841, when Sir George Everest, surveyor general of India, recorded its location; the first reasonably accurate measurement of the mountain was subsequently made in 1856. The first British reconnaissance expedition was made in 1921, and since then mountaineers of various nationalities have tried to reach the roof of the world. On 8 June 1924 George Mallory and Andrew Irvine were spotted from below going over one of the last major obstacles to the summit, only a few hours away. But their companions lost sight of them in the mist and their disappearance left unanswered a question that has haunted mountaineers ever since: did they reach the top? In 1999 Mallory’s body was found at c. 8,100m, but the question remained unanswered: was he on the way up or on the way down?

The significance of peacetime exploration

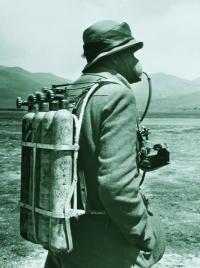

Testing oxygen apparatus for the 1924 expedition. (Trinity College, Dublin)

During peacetime the successful exploration of new territories reflected the power and prestige of a country. Having lost the race to the North and South Poles, the British wanted to be first to reach ‘the third pole’, the highest mountain on Earth. The south route to Everest, commonly used by explorers from later in the twentieth century up to today, was not then accessible, as westerners were not allowed to travel through Nepal. Taking the north route was politically complex, as it required the persistent intervention of the British-Indian government with Tibet’s Dalai Lama in order to sanction activities. The north route also allowed for only a short window between the end of winter and the start of the monsoon season.The first expedition in 1921 was an exploratory one, while the second, in 1922, attempted to make the first ascent. The following year there were no resources to continue, so the third expedition was postponed until 1924. The participants were selected not just for their mountaineering skills. Factors such as the status of their families, military experience and university education were also important. Amongst them was an Irishman, Richard William George Hingston. He was not a mountaineer but the expedition’s medical officer and naturalist.In The fight for Everest, 1924, the leader of the expedition, Edward Norton, described the characteristics of the team members, observing that Hingston arrived as fit as possible after a harsh Mesopotamian winter. In his double role as the doctor and naturalist he had his hands full, and ‘in his first capacity he came bursting with energy and enthusiasm to test every member of the expedition with every terror known to the RAF authorities’. He not only brought his professional abilities but also a placidity of temperament and an unfailingly humorous outlook. As Norton recalled:

‘I shall be intensely obliged if anyone can point out a better make-up for the trying duties which he was asked to carry out. All our thanks are due to him. Hingston was not a mountaineer. Oh no! But read to the end of this book, and then make a comment on this statement.’

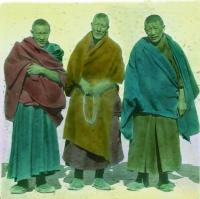

Tibetan monks immobile for a long-exposure photograph. Note the blurred hands of the middle one, still counting mantras on his beads. (Trinity College, Dublin)

Hingston’s journal

In his journal (now held by Trinity College library) Hingston describes his daily activities in depth, and we find him busy collecting specimens, vaccinating porters and making observations on the effect of high altitude on human health. He starts his daily entries not only with a date and place but also with the altitude. There was some entertainment on the way, too. On 13 March 1924, at 7,000ft in Darjeeling, he writes that a large party of Americans on a tour around the world arrived in the morning at the hotel:

‘They persuaded the General [C.G. Bruce] to give a talk to them on Everest, which he gave for about twenty minutes. After dinner they witnessed a Lama dance. The Tibetans had dressed themselves in fantastic costumes, with large masks representing caricatures or animals. The dance was symbolic and of a semi-musical character and the music a strange and long drone.’

This leisurely beginning was followed by a series of difficulties as the group reached ever-higher altitudes. Norton praised Hingston for his professionalism when the leader was struck by snow-blindness. Hingston had already displayed a cool head traversing the glacier as far as camp III, so it wasn’t a surprise when he arrived in camp IV ‘with the matter-of-fact ease of an experienced mountaineer’. Impressed by Hingston’s remarkable performance, Norton concluded that the doctor gave him ‘the impression of steadiness and confidence of an Alpine guide’. On 6 June the doctor found Norton absolutely blind and he had to get him down, as the camp was situated on a shelf of ice ‘with nothing but a strong white glare all round’, the worst possible situation for a snow-blind man. N.E. Odell and J. de V. Hazard were in the camp, acting as a support for Mallory and Irvine, who were then making their attempt to reach the summit. Hingston seemed to enjoy the climb, but he had to go back to his duties: ‘I could not remain at camp IV, though I should have liked to look longer in the sea of mountains visible from such height’. Norton was able to walk but he could see nothing in front of him; at every step Norton’s feet had to be placed. It was a great relief when they managed to get down.When Mallory and Irvine made their attempt to reach the summit, Hingston described the tense period of waiting in vain for their return. On 10 June he wrote:

‘There can be no doubt, the worst has happened. Not a sign of Mallory and Irvine. They must have slipped near the summit and the face of the mountain. This is a bad ending and a serious loss . . . It is certain to cause talk and criticism, though nobody is in the slightest to blame. Odell with his porters is in the search all day . . . We received a signal in the evening that all hope was abandoned.’

He adds in a reflective tone:

‘Everest is a most dangerous mountain. In three expeditions it has claimed twelve victims. It is just possible that Mallory and Irvine may have climbed it.’ HI

Justyna Pyz is a research associate with the Ireland, Empire and Education Project at Trinity College, Dublin (www.irelandempire.ie).

Further reading:

R.W.G. Hingston, Naturalist in Himalaya (London, 1920). R.W.G. Hingston, ‘Physiological difficulties in the ascent of Mount Everest’, The Alpine Journal (1925).E.F. Norton, The fight for Everest, 1924 (Varanasi, 2004).Hingston’s journals and documents can be viewed at http://digitalcollections. tcd.ie/home/.