‘The loveliest thing ever made by an Irishman’: Harry Clarke’s Geneva Window

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 2(March/April 2011), Volume 19

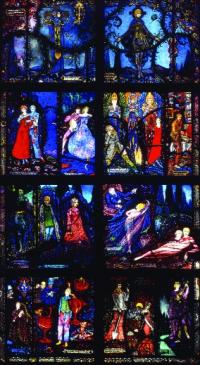

The complete Geneva Window, with its eight panels representing fifteen Irish writers—(1) The wayfarer by Patrick Pearse and The story brought by Brigit by Lady Gregory; (2) Shaw’s St Joan; (3) Synge’s The playboy of the western world and Seamus O’Sullivan’s The others; (4) James Stephens’s The demi-gods and O’Casey’s Juno and the paycock; (5) The dreamers by Lennox Robinson and Yeats’s The Countess Cathleen; (6) O’Flaherty’s Mr Gilhooley and Æ’s Deirdre; (7) Padraic Colum’s A cradle song and The magic glasses by George Fitzmaurice; and (8) The weaver’s grave by Seamus O’Kelly and Joyce’s Chamber music. This final panel is signed ‘Harry Clarke Dublin 1930’. (Wolfsonian Museum)

Harry Clarke was the leading stained glass artist of his day. Mainly working on churches, most notably UCC’s Honan Chapel, he was also well known as a book illustrator. After W.T. Cosgrave, president of the Irish government, opened an exhibition in his Studios in North Frederick Street in 1925, Clarke was approached in 1926 to create a window for the Irish office in the International Labour Court in Geneva. This would be his most prestigious project as the Free State was anxious to make a good impression on the international stage.

Clarke visited Geneva in 1926 and got measurements of the proposed window. (He had by then contracted tuberculosis and would become a regular visitor to sanatoria in Switzerland.) Owing to other commissions and his ill health, the window was delayed but Clarke had decided that the work of fifteen modern Irish authors would be its subject. The plans were submitted to the government, which approved the idea. Cosgrave agreed to unveil the window when it was installed.

In May 1930 the window was put on display in Clarke’s Studios. He was worried by the muted reception it received from cabinet ministers and the press. His anxiety was borne out when Cosgrave sent a letter expressing unease especially with the Mr Gilhooley scene from Liam O’Flaherty’s novel. Cosgrave said that ‘considerations arise where a window is being presented on behalf of the government which in the ordinary course would not occur to the artist’. In another letter he made clear the objection to ‘scenes from certain authors as representative of Irish literature and culture [which] would give grave offence to many of our people’.

The panel in question features two naked women, but it was the overall character of the window that caused concern. There was a feeling that the image of Ireland presented was not a desirable one, as among the writers featured were Protestants and Catholics of dubious morality like O’Flaherty and Joyce. As well as nudity, the window portrayed poverty, prostitution, drinking and dancing, not things the government wanted associated with Ireland.

In retrospect it is difficult to imagine what Cosgrave and his colleagues expected from Clarke. Although he

![The offending panel 6—‘She came towards him dancing, moving the folds of the veil, so that they unfolded slowly, as she danced’ (Mr Gilhooley by Liam O’Flaherty, top left-hand corner); ‘I know the great gift we will give to the Gael will be a memory to pity and sigh over; and I shall be the priestess of tears’ (Deirdre by George Russell [Æ], bottom right-hand corner). (Wolfsonian Museum)](/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/84_small_1299515428.jpg)

The offending panel 6—‘She came towards him dancing, moving the folds of the veil, so that they unfolded slowly, as she danced’ (Mr Gilhooley by Liam O’Flaherty, top left-hand corner); ‘I know the great gift we will give to the Gael will be a memory to pity and sigh over; and I shall be the priestess of tears’ (Deirdre by George Russell [Æ], bottom right-hand corner). (Wolfsonian Museum)

The ailing Clarke was increasingly anxious about the fate of the Geneva Window. He returned to Switzerland for treatment in October 1930 but continued to correspond with the government. He wanted to protect his artistic integrity and also to get much-needed funds for his Studios. This correspondence continued right up to his death on 6 January 1931. Three weeks later his widow, Margaret, received £450 and notification that the window would be housed in government buildings in Merrion Square. She did not let the matter rest there, however, as she did not want her husband’s last, and possibly greatest, masterpiece to be hidden away. In 1932 the minister for industry and commerce in the new Fianna Fáil government, Seán Lemass, sold the window back to her.

Although shunned by official Ireland, the window had its champions. Clarke’s friend and patron Thomas Bodkin described it as ‘the loveliest thing ever made by an Irishman’. It was displayed in the Hugh Lane Gallery and the Fine Art Society in London. Finally, in 1988 Clarke’s sons, David and Michael, sold it to a wealthy American art collector, Mitchell Wolfson, who put it in his museum in Miami Beach, Florida, where it now has pride of place. Given its history, some regard it as fitting that we lost the window. As noted commentator Brian Fallon said, ‘We have, quite simply, disgraced ourselves again’. HI