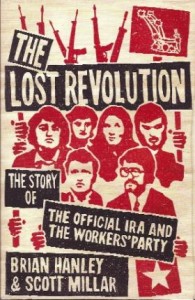

The lost revolution: the story of the Official IRA and the Workers’ Party

Published in 20th Century Social Perspectives, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Book Reviews, Issue 1 (Jan/Feb 2010), Reviews, Troubles in Northern Ireland, Volume 18Brian Hanley and Scott Millar

(Penguin Ireland, €20)

ISBN 9781844881208

The front page of the September 1971 Official Republican paper The United Irishman displayed a photograph of a gunman crouched under a Starry Plough flag and silhouetted against a blazing truck. (See ‘Second glance’ on pp 46–7.) The headline read ‘Army of the People’, and the picture showed south Belfast Official IRA staff captain Joe McCann in action during one of the fierce gun-battles that followed the introduction of internment on 9 August that year. September’s Provisional Republican An Phoblacht ran the same picture on its front page with the caption ‘IRA volunteer manning barricade in Markets area’. That cheeky piece of Provo journalistic piracy serves as a graphic reminder that at the time there were two, rival, IRAs, and that while the Provos by then outnumbered and outgunned their ‘Sticky’ competitors, the Official IRA remained a formidable force within the world of republican paramilitarism.

The front page of the September 1971 Official Republican paper The United Irishman displayed a photograph of a gunman crouched under a Starry Plough flag and silhouetted against a blazing truck. (See ‘Second glance’ on pp 46–7.) The headline read ‘Army of the People’, and the picture showed south Belfast Official IRA staff captain Joe McCann in action during one of the fierce gun-battles that followed the introduction of internment on 9 August that year. September’s Provisional Republican An Phoblacht ran the same picture on its front page with the caption ‘IRA volunteer manning barricade in Markets area’. That cheeky piece of Provo journalistic piracy serves as a graphic reminder that at the time there were two, rival, IRAs, and that while the Provos by then outnumbered and outgunned their ‘Sticky’ competitors, the Official IRA remained a formidable force within the world of republican paramilitarism.

On the political front, in 1989 the Workers’ Party won seven seats in Dáil Éireann, gaining group status, procedural privileges, secretarial backup and £50,000 in public funding. Sinn Féin has yet to cross that threshold. But, as it turned out, 1989 marked the high tide of Workers’ Party electoral performance. Within three years, six of the seven TDs departed the ranks to form Democratic Left, and eventually to merge with the Labour Party. Tomás Mac Giolla stayed on, a one-man rump, only to lose his seat at the next election. The Workers’ Party faded into what the English republican, John Milton, would have recognised as a ‘Godly remnant’—marginalised, stalwart and devout. The ideology had changed, but for a few senior party veterans there was nothing new about the political wilderness; it was from there, after all, that as young men they had set out on their journey in the 1950s.

Book publishers’ claims printed on back covers need to be treated with due caution, yet the claims made on the back of this book ring true: ‘The story of contemporary Ireland is inseparable from the story of the Official republican movement, a story never before told’. Certainly it is a story never before told in such luxuriant detail, one which the authors, Brian Hanley and Scott Millar, choose to begin in the 1950s, when several of the men who would later lead the Officials—Cathal Goulding, Seán Garland, Mac Giolla—came to prominence or launched their careers in traditional, physical-force, irredentist Irish republicanism. A chronological treatment is sustained thereafter, although that is not as straightforward as it might seem, since the authors have to keep at least four balls—the military and the political, north and south—in the air at one time.

The 1956–62 border campaign has received scant attention from historians, presumably because from a post-1969 perspective it appears such a small-scale affair. But the experience of failure shaped the course of republican politics for a generation. Garland participated in the raid in which Seán South and Fergal O’Hanlon were killed. Proinsias de Rossa, future president of the Workers’ Party, Democratic Left and the Labour Party, marched as a Fianna boy at South’s funeral. Not since J. Bowyer Bell’s The secret army, greeted by Goulding upon its publication in 1969 as ‘not just a book about the IRA, but a book for the IRA’, has the border campaign received such close scrutiny, for, like The secret army, Lost revolution is concerned more with the lasting impact which that campaign had on the IRA than on the minor effect it had, north and south, on Irish politics and society.

In 1965 IRA chief-of-staff Cathal Goulding joined Sinn Féin, signalling a shift away from military and nationalist purism towards political agitation on social and economic issues. That historic reorientation resulted from the reappraisal of strategy and objectives demanded by the failure of the border campaign. Wolfe Tone societies were founded in 1963, the bicentennial of Tone’s birth. Roy Johnston and other former members of the British Communist Party returned to Ireland and caught Goulding’s ear. The new ‘New Departure’ had a distinct, still pliable, left-wing complexion and a 1960s folk-revival soundtrack (Dominic Behan’s ‘Patriot Game’ was the first revisionist rebel ballad). In the South republican activists joined in or led industrial disputes, housing action committees, ‘fish-ins’ and campaigns against ground rents. In the North they played a pivotal role in the emerging civil rights movement.

At the outset of these processes Goulding, mindful of his comrades’ rather Protestant propensity to split over doctrinal principle, vowed to ‘take the whole movement’ with him. Some traditionalists simply drifted away, but more than enough remained to block ‘progress’ and to vote down attempts to drop parliamentary abstentionism. The traditionalists, epitomised by Seán Mac Stíofáin, distrusted politics in general, and took a hostile, Cold War, Catholic view of atheistic Marxism. Roy Johnston once tried to persuade Mac Stíofáin of the possibilities of a Catholic–Socialist synthesis by introducing him to the films of the Italian director Pasolini. He did not succeed, and the following year Mac Stíofáin was suspended from the Army Council for refusing to sell The United Irishman in his district because it contained a letter from Johnston calling for an end to the practice of reciting the rosary at republican commemorations. Such inevitable internal tensions were brought to snapping-point by the Northern crisis that erupted onto the streets of Derry and Belfast in August 1969. Critics asserted that in its turn to politics the IRA leadership had run down the army and left the Catholic community in the north almost defenceless against loyalist onslaught. Thus began the legend ‘I Ran Away’, the origin myth of the Provisional IRA.

For the most part Hanley and Millar eschew explicit analysis in favour of presenting the information that they have amassed—much of it based on years of interviews with participants in the events that they describe—in a coolly non-judgemental, nearly chronicle-like, narrative. They do, however, in classic revisionist fashion, knock out the myth of what one Official called ‘all that crap about 1969’. The rebuke ‘I Ran Away’ did not pop up overnight daubed on the gable walls of west Belfast. The first traceable reference to that slogan dates, in fact, from April 1970, when a priest testifying before the Scarman Tribunal recalled hearing it. The IRA did not run away but, poorly armed, put up a creditable if inadequate defence of Catholic areas, and at the time Gerry Adams was ‘perturbed and perplexed’ by ‘the extreme criticism’ being levelled at the Belfast leadership.

But myths, no matter how inaccurate, have operative force in history, and giving lie to the ‘rusty guns’ taunt is surely one of the reasons why the Official IRA stumbled into armed conflict with the British army, on the 3–4 July 1970 fighting what it described as ‘the single biggest engagement with British Crown forces since 1916’ on the Falls Road in Belfast. This led to the imposition of the first and only curfew of the Troubles. The Official IRA adopted a policy of ‘defence and retaliation’, but since there was plenty to retaliate for in practice there was little to distinguish its activities from the Provisional campaign. After calling a ceasefire in 1972, and as the primacy of politics was reasserted, military activities gradually wound down. As Sinn Féin became Sinn Féin the Workers’ Party and Sinn Féin the Workers’ Party became the Workers’ Party, the Official IRA quietly slipped into the shadows. The Party now publicly denied its existence. ‘The Army of the People’ became ‘Group B’. Yet despite (or perhaps because) of its lower profile, the Official IRA reputedly represented the ‘most serious’ ‘long-term threat’ to the state in both jurisdictions—a flattering self-estimate shared at various moments during the 1970s by the British security services, Irish military intelligence, some Catholic bishops, the Belfast News Letter, the Irish Times and the UVF. In 1976 the minister for justice, Patrick Cooney, downgraded the ‘Sino-Hibernian’ Marxist threat to mere equality with that posed by the Provisionals, although some less well-informed Sino-Hibernians continued to believe that they would ‘out-Provo the Provos when the crunch came’.

Group B constituted one secret subsection of the Revolutionary Party, the Industrial Department another. In the late 1970s the Industrial Department, under the direction of Eoghan Harris and Eamonn Smullen, penetrated the trade union movement, most notoriously in RTÉ, and, in what might be termed its high Stalinoid period, achieved hegemony within the party. The Stalinoid style is reflected in the endless rooting out of heresy—‘ultra-leftists’, ‘instant revolutionaries’, ‘Trots’ and, inside RTÉ, the vilest of all deviants, ‘Trotskyite-Provos’—and in the ‘economistic’ strategy set out in The Irish Industrial Revolution, a manifesto to create full employment, and thereby strengthen the Irish proletariat, by attracting multinational corporate investment and expanding the public sector. The authors, who rarely venture an opinion, describe this influential polemic as ‘utopian’. They kindly refrain from passing any verdict on either the silly ‘historical’ section of the Industrial Revolution or on Smullen’s contemporaneous musical about youth unemployment.

Looking back, Dr John McManus thinks that ‘opposition to the Provos [is] possibly the party’s finest legacy’. That is a most revealing view, because if one thing sticks out from the dense thickets of detail in this book, it is how opposition to the Provo ‘other’ ultimately defined Official republicanism. Rivalry turned into raison d’être, white whale and way of life. With all the zeal of the convert, the sanctimonious reformed alcoholic or the stridently anti-communist ex-communist, the Provos were flailed as xenophobic, Catholic-nationalist, Fascist-terrorists. As much psychological condition as political conviction, the remorseless logic of being ‘not-Provo’ drove some Workers’ Party intellectuals into the counsels of Ulster Unionism and others into the not-unrelated and agreeably predictable ‘opinion’ pages of the Sunday Independent. Party spokespersons supported Section 31, ‘supergrasses’ and even, ‘as a very last resort’, internment. Condemning violence and sectarianism is a principled and at times courageous position to take. What rankled with critics in light of the party’s own colourful past is that, as former party activist Paddy Woodward put it, ‘they came on like a bunch of choirboys’. Opposition to violence was also, surely, correct. Asked about the Good Friday Agreement, Goulding remarked: ‘We were right, but too soon. Gerry Adams is right, but too late.’ Better late than never. HI

Jim Smyth is Professor of History at the University of Notre Dame.