THE LIMERICK SOVIET 1919

Published in Features, Issue 5 (September/October 2022), Volume 30By John Lonergan

Above: Bishop Michael Fogarty of Killaloe, a significant supporter in the initial stages of the Soviet.

A soviet is an elected workers committee functioning as a political and military organisation. The Limerick Soviet was the first and only self-declared soviet in Ireland or Britain, existing from 14to 27 April 1919. It resulted from a strike declared by the Limerick United Trades and Labour Council, protesting against the proclamation of the city as a ‘special military area’ under the Defence of the Realm Act. The British Army now had the power to issue permits, restricting access to the city. The permits held the applicant’s personal details, and they were stamped and dated when passing through the military cordon.

A trigger point was the British Army’s response to Robert Byrne’s death and funeral. Byrne was chairman of the Limerick branch of the Irish Post Office Clerks’ Association. In addition, just before Christmas 1918, he had been appointed adjutant of the IRA’s 2nd battalion, Limerick Brigade. He was dismissed from his job for attending the funeral of Limerick Fenian, John Daly. Soon afterwards, Byrne was charged with possession of a firearm and sentenced to two years in prison, and subsequently went on hunger strike. In March 1919, Byrne was removed to the City Infirmary. On 6 April 1919, the IRA launched a rescue operation, but Byrne was shot and died. His funeral on 10 April was subject to a military order designed to suppress the numbers attending. Soldiers with fixed bayonets took up positions along the cortege route and two military aeroplanes circled above the procession for part of the way. Nevertheless, 15,000 attended the funeral.

Above: The funeral of Robert Byrne, chairman of the Limerick branch of the Irish Post Office Clerks’ Association and adjutant of the IRA’s 2nd battalion, Limerick Brigade, on 10 April 1919. In spite of British Army attempts to suppress it 15,000 attended. But note the British officers saluting. (Liam Cahill)

Soviet declared on 15 April 1919

On Monday 14 April, workers in Cleeve’s Condensed Milk and Butter Factory went on strike. Later, the Trades Council called a general strike throughout the city. 15,000 workers were now on strike, which the Evening Herald said was a ‘struggle between organised labour and government’. The Trades Council transitioned into a strike committee, with John Cronin as chairman. The Limerick Soviet was officially declared on Monday 15 April 1919 with the strike committee stating that it was ‘a protest against the decision of the British Government in compelling them to procure permits in order to earn their bread’.Sinn Féin and the Catholic Church were faced with the dilemma of supporting or condemning the strike. However, as the strike was overwhelmingly popular with workers, condemning the strike would result in both conceding its working-class support. Therefore, they decided to condemn the military cordon and called for the British Army to withdraw from the city. The Catholic Church was a significant supporter in the initial stages of the Soviet:

‘The clergy appealed to the people to aid Limerick with food supplies and announced that they did so with the sanction and good will of Most Revd. Dr Fogarty, Bishop of Killaloe. There was a generous response to the appeal, including the gift of twenty tons of potatoes.’

Who was in control?

Throughout the country, food was collected by clergymen and sent to Limerick. Opinion is divided on whether the IRA was involved in the Limerick Soviet. Liam Cahill argued that the ‘speed and efficient way that the Trades Council was organised would seem to underline a degree of Sinn Féin influence and support’. D.R. O’Connor Lysaght concurs, stating that ‘the Unionist press regarded the Soviet as no more than a front for Sinn Féin’.This was echoed in commentary in the contemporary press, who said there ‘is something about the methods of the Limerick Strike that smacks strongly of the Sinn Féin organiser. The voice is the voice of the worker, but the hand is the hand of Harcourt Street.’ Dominic Haugh on the other hand argues that this was a workers’ revolt, with the ITGWU and the labour movement completely in control, actively seeking to better and protect the working conditions of the city’s population. This is supported by the non-violent nature of the strike, and the huge emphasis of the strike committee on making life easier for the poorer, working classes. The IRA exception was Michael Brennan, commandant of the East Clare Brigade. Brennan was drafted onto the strike committee so the Soviet would have the assistance of armed men if needed and to ensure that the considerable presence of IRA in the city would not become outwardly hostile to the Soviet. While IRA members were without a doubt involved in the strike, it is clear the organisation itself was not officially involved.

Most industries followed the strike committee’s instructions to close, except the Post Office and the banks. The strike committee maintained essential supplies of water, gas and electricity but switched off public lighting. Ensuring constant food supplies was a problem due to a lack of coal and flour, with restaurants, hotels, and pubs shut. Bakery ovens were fired by coal, but coal merchants frequently refused to open their yards, and received police protection. However, the strike committee’s efforts to secure supplies were commended by the Irish Examiner:

‘The strike committee’s efforts to cater for the wants of the people … are certainly most commendable, and their food deposits … are working to the most satisfactory manner … large quantities of potatoes, milk, butter, and flour reach these deposits and are retailed to customers at very reasonable prices. These measures help in a large measure to stem the food shortage.’

Prices of goods were fixed by a subcommittee, with flying pickets enforcing the price controls and order in the queues. The Soviet issued permits to merchants so that they could acquire and transport goods such as coal, butter and flour. Only vehicles with permits were allowed to move throughout the city; all other vehicles were forced off the street by the patrols.

British response

The British Army was surprised at the declaration of the strike since martial law was not uncommon during the War of Independence. Within half an hour of the strike proclamation, local police chiefs were communicating with Dublin Castle requesting 300 additional constables; 50 were dispatched. Police and military were confined to barracks for safety while their commanders decided what to do. Commander General Griffith was front and centre of all British military and diplomatic responses, targeting the Chamber of Commerce as allies. He set out a compromise that employers in the city would be able to issue permits to their employees, instead of the military. This would make it easier and quicker to obtain a permit. On 17 April, the Bishop of Limerick, Dr Hallinan, and the mayor, Alphonsus O’Mara, met secretly with Griffith who agreed to withdraw the military permit order within the week if there was no trouble.

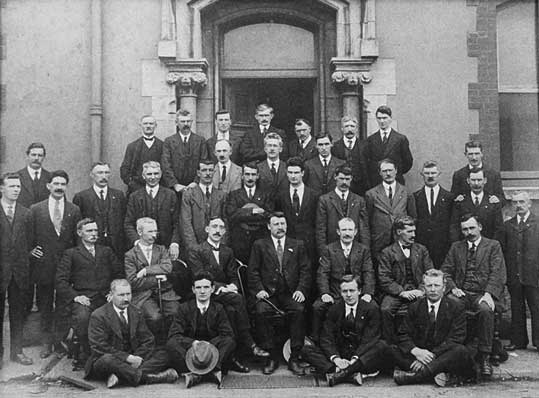

Above: The strike committee of the Limerick Soviet, with chairman John Cronin in the centre of the second (seated) row.

ILPTUC response

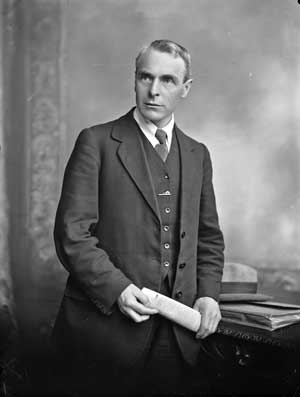

The strike committee looked to the Irish Labour Party and Trade Union Congress (ILPTUC) for support. On Wednesday 16April, the ILPTUC sent its treasurer, Tom Johnson, to Limerick. While the ILPTUC nominally supported the strike, it did not have revolutionary tendencies, and was reluctant to give any substantial show of support. In addition, it had neither the physical means nor the political consciousness among its members to pursue such a strategy.

On Saturday 19 April, a public meeting was held in City Hall, chaired by O’Mara. John Cronin addressed the meeting, saying that the ILPTUC national executive would be relocating from Dublin to Limerick, to show their support for the strike. Cronin said that he expected the executive would take over the organisation of the strike and that the ILPTUC delegates could call a national general strike. Johnson avoided any commitments, saying that the delegates would arrive at the earliest on the Tuesday 22 April. ILPTUC chairman, William O’Brien, was against a railway strike, arguing that it would hurt the working class and not the British military, but that ‘National Action would soon be taken’. While nominally in support, O’Brien actively undermined the Soviet and had no intention of calling such a strike. He met with the Sinn Féin leadership who did not want the Limerick Soviet to escalate and most probably instructed

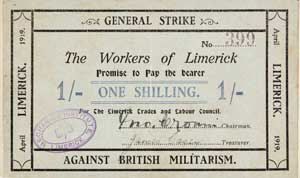

Above: ‘The Workers of Limerick Promise to Pay the bearer’—a one shilling Limerick Soviet note signed by chairman, John Cronin, and treasurer, James Casey.

Currency issued

Still, the strike committee maintained control. The Sunday Independent stated that‘order still prevails in Limerick’. When it was rumoured that some business owners would open their shops, the strike committee made it clear that flying pickets would close them down. By the second week, the strike committee was under financial pressure. The IGTWU gave £1,000, the GAA gave money, as did the Bishop of Killaloe, Michael Fogarty, and his clergy. The Soviet was dependent on donations, as it had no infrastructure for collecting taxes. In any case, it was not keen to tax the workers on which it depended for support. So, the Soviet issued a currency in 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, 5- and 10-shilling notes, signed by James Casey (treasurer) and Cronin (chairman). They were ‘issued and accepted by shopkeepers’. The notes were printed at the Record Printing Works and were the same size as regular treasury notes. On the back they had ‘General Strike against British Militarism 1919’ and on the face it had ‘The Workers of Limerick Promise to Pay the bearer the sum of __ shillings’. These notes were in the form of promissory notes, where strikers could purchase necessities, exchange a note and the Soviet promised to redeem the notes when the strike was over.

The end

On Wednesday 23 April, IGTWU representatives arrived in Limerick, including Johnson, Thomas Farren (vice-chairman), and members from various unions. The IGTWU’s offer that the Limerick workers evacuate the city was revisited and rejected by the strike committee. After this, a considerable amount of time was spent by the ILPTUC’s delegation convincing the strike committee to abandon the strike in Limerick. Several thousand workers staged a protest outside the Mechanics Institute while the executive and Soviet met inside, making it clear that the workers in the city still supported the strike and its continuation. On Thursday 24 April, Dr Hallinan and O’Mara sent a letter urging the Soviet to end the strike. With Sinn Féin, the Chamber of Commerce, the Church and the ILPTUC all opposed, the Soviet had run out of road. Cronin and Johnson announced that the strike was finished. Johnson called on all workers to resume work as soon as possible. However, an element of anger persisted in the air. There were rumours that the protestors would ‘supplant the strike committee’.On Friday 25 April, about half of the workers in the city went back to work. Later, at Sarsfield Bridge on Saturday 26 April, demonstrators supportive of the Soviet’s continuation stopped permit holders from crossing until they were forcibly moved by the police. Reactions from trade unions in Britain to the Soviet were overwhelmingly negative, regarding the strike as ‘political’ as opposed to an industrial relations issue. There was a national media campaign attacking the Soviet, the Irish Times stating:

‘We think that the experiment will fail … the people and indeed every section of the community are greatly elated that the strike is over and that peace and good order that prevailed all through the continuance has remained undisturbed to the end.’

Above: Tom Johnson, treasurer of the Irish Labour Party and Trade Union Congress (ILPTUC), whose support for the Soviet was never enthusiastic. (NLI)

The British chief secretary, Ian McPherson, stated that ‘the crisis that might have developed if the authors had their way, is now over’ and that ‘[the British] were glad that the wiser and more experienced leader of labour had been among the first to condemn such a reckless, arbitrary, and reprehensible manipulation of industrial means for political ends’. The ILPTUC had sold out the strike and the head of the British imperialist presence in Ireland thanked them for their help. The Limerick Chamber of Commerce was critical of the strike, estimating it to have caused losses of £42,000 in wages and £250,000 in turnover and denounced the lack of consultation and notice for the strike. The financial situation was another crucial factor in the brevity of the strike. Afterwards, the ILPTUC estimated that £7-8,000 per week was needed to fund the Soviet. Only £1,500 had been collected by the end of the strike. The other big problem was the lack of food. The city was beginning to feel the ‘food pinch’, with cases of backdoor trading ‘keeping the strike pickets extremely busy’.

Significance

One possible assessment of the Limerick Soviet would suggest that it had a limited impact on the public consciousness and Irish history, only existing for ten days. In my opinion the reasons for its downfall were twofold. Firstly, the strike committee accepted the leadership of the ILPTUC, folding very quickly after the ILPTUC expressed an opinion contrary to the committee. Consequently, the Soviet lacked widespread national trade union support. Secondly, the ILPTUC was not willing to fight for the cause or put itself at the forefront of the struggle for political, social, and economic emancipation for the working class. An interesting way of looking at it is the potential it could have had. If the Limerick Soviet had achieved a more sustained success against the British government and military, Sinn Féin and the IRA would have been forced to pay more attention to the Labour movement’s economic demands. The Labour movement might have found itself in a more powerful position to influence the Irish Free State. The ILPTUC later argued that they had no power to call a nationwide strike. This was an excuse, disproved when the ILPTUC called a general nationwide strike for two days to force the British authorities to release hunger striking prisoners from jail.

John Lonergan is a student in St Kevin’s College, Ballygall, Finglas.

Further reading

D. Haugh, Limerick Soviet 1919: the revolt of the bottom dog (Limerick, 2019).

L. Cahill, Forgotten revolution: Limerick Soviet 1919: a threat to British power In Ireland (Dublin, 1990).

D.R O’Connor Lysaght, The story of the Limerick Soviet (Limerick, 2003).

J. O’Callaghan Limerick. the Irish revolution 1912-23 (Dublin, 2018)

The closing date for submissions for the 2022-23 competition is 31 March 2023. Details here https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/cf8d7-history-competition/