The Leinster Regiment and the Malabar rebellion of 1921—‘another Irish question’

Published in Features, Issue 4 (July/August 2021), Volume 29By Terry Dunne

On 20 August 1921 a band of Irishmen were making a fighting retreat in south-west India at the start of the Malabar rebellion. They were men from the Calicut garrison of the 1st Battalion Leinster Regiment. This was the last combat of the southern Irish regiments of the British Army, as these units were disbanded the following year. Malabar was then part of the Madras Presidency, part of the British Empire, just like Ireland. The final colonial campaign of a southern Irish regiment offers us a useful vantage point from which to consider Ireland’s place within the British Empire. In the 1790s, armies commanded by Irishmen incorporated the Malabar region into the British Empire; later British officials thought about Malabar through Irish analogies; and Irish separatists extolled the 1921 rebels as the first green shoots of a wider Indian revolution.

Irish analogies

More important than these connections, however, is the possibility of a comparative understanding of colonialism and class-based resistance to colonialism. We can start our journey with an 1844 document penned by a British official, effusively pontificating on the apparent Irish-like aspects of the Mappilas, the Muslim community in Malabar, whom he referred to as ‘moplahs’:

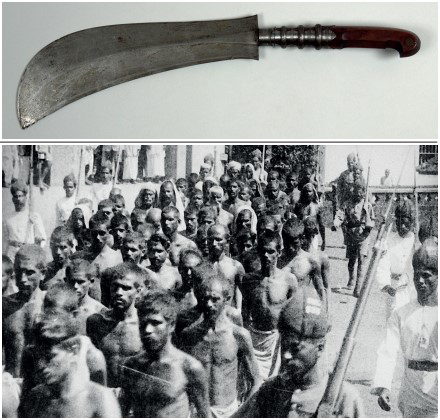

‘Ill blood is frequently created between moplahs and hindoos on account of land disputes … but how these are to be avoided, so long as the rights of the proprietor are allowed, is as difficult a question in Malabar as it is in Ireland. I trust not to expose myself to the charge of exaggeration in expressing an opinion that a remarkable analogy exists in many respects between the circumstances of the two countries when disturbed. In both, the land owners (generally) are of a different religion to their tenants, in both, the tenants are an ignorant bigoted people who may be led to any excess on the instigation or supposed sanction of their religious instructors, in both, it seems, believed that the murder of a heretic is a passport for heaven, in both, the blood of landlords is shed without scruple where any cause of complaint is imagined against them, in both, these murders are sympathised in by the body of tenants generally … it would apparently follow, that measures which are considered necessary for a disturbed part of Ireland, are … necessary for a disturbed part of Malabar. I must confess I do not see why the moplah should be allowed his war knife while the Irishman is prevented from having his pike.’

Initially this appears to be the same self-serving racist disdain applied to one colonised people as to another. We even see the priestcraft trope of anti-Catholicism conjured up to describe the very differently organised Muslim faith. What complicates the picture, though, is the fact that the author of the above document, although born in London, was the possessor of the fine old Gaelic surname of Conolly. This underlines the main point here: we need to use class as a central concept to understand the varied experience of colonialism, which the lens of a homogenising nationalism cannot encompass. In the Irish case, the Great Famine (1845–52) is rightly seen as the nadir of British rule, but Irish landlords evicted Irish tenants, Irish farmers evicted their Irish subtenants, and Irish merchants exported Irish foodstuffs. Similarly, we have to understand that class relations do not operate in a social vacuum but intersect with confession, caste or citizenship status, as well as with gender.

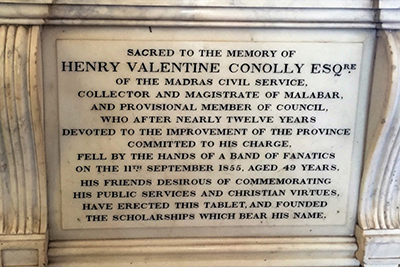

Henry Valentine Conolly

Above: ‘… FELL BY THE HANDS OF A BAND OF FANATICS …’—memorial tablet to Henry Valentine Conolly in St George’s Cathedral, Madras.

Henry Valentine Conolly was drawing comparison between Ireland’s Whiteboys and Malabar’s shahids. ‘Whiteboys’ refers to a succession of insurgent agrarian movements beginning in Tipperary in the 1760s and running into the middle of the nineteenth century. In addition, more comparatively isolated actions, including assassinations, occurred outside the time-frame of any particular mobilisation. Elsewhere in the document Conolly specifically refers to the assassination of the Earl of Norbury at Durrow, near Tullamore, in 1839, an assassination that was carried out in retaliation for some evictions. Ironically, that killing took place in the middle of what was to become the recruiting ground for the Leinster Regiment. The next earl fled the county after his house was burned down in 1844. Contrary to Conolly’s characterisation of sectarian polarisation, however, Ulster saw predominantly Presbyterian movements parallel to the Whiteboys—the Hearts of Oak, the Hearts of Steel and the Tommy Downshires—while in Malabar the Muslim proportion of the population grew owing to the conversion of people from the lower ends of the caste hierarchy.

Above: Recruitment poster for the Leinster Regiment. (NAM)

The particular tradition of resistance in nineteenth-century Malabar, the practice of the shahids or martyrs, involved an individual or small group undergoing religious rituals, assassinating a landlord or a landlord’s agent, and then giving their lives in combat with the forces of the Crown. There was a rate of roughly one incident per year between 1836 and 1854, decreasing to only one attack every four or five years between 1855 and 1887. Henry Valentine Conolly himself was to become the highest-status victim, falling to the assassin’s blade on 11 September 1855. Interestingly, while the cult of martyrdom is familiar to us from Irish nationalist tradition, where it also had religious overtones, it did not feature greatly in Irish agrarian social conflict. Of particular comparative interest is the shift in the Malabar repertoire away from the shahid model towards less violent forms towards the end of the nineteenth century. A factor here was likely the fact that the State at least gave the appearance of moving in a more ameliorative direction. Notably this change in repertoire was paralleled in Ireland in the move from the era of the Whiteboys to the era of the Land War. In both places there was a marked change in emphasis in the State’s legislative framework in a direction that differed from the straightforwardly pro-landlord stance of the past.

Conolly was part of the ‘fanatic school’ of British administrators in Malabar who interpreted local resistance in terms of some moral failing on the part of the resistors. In later decades a more revisionist school came to the fore and understood the origins of the conflict in terms of how British law had bolstered landlord power. This ‘pro-tenant’ school argued that reasons of security necessitated some rebalancing and readjusting away from the old policy. The reform tendency also used Irish analogies—the comment ‘It is another Irish question’ headlines the minutes of some of the discussion that led to the first piece of pro-tenant legislation for Malabar. From that perspective we can understand something of how class and colonialism interrelated and how a figure like Conolly was not an aberration or an anomaly but was perfectly congruent with the general course of the Irish past.

Imposition of an exclusive model of private property

The immediate impact of the incorporation of Malabar into the British Empire was to turn local rulers called jenmis from receivers of tribute into owners of the soil, to impose an exclusive model of private property and to turn customary forms of tenure into market-determined rents. This was all the more marked a change since many jenmis had fled before the advance of the Mysore Sultanate. The year 1799 saw the final defeat of Mysore, the state headed by the famous Tipu Sultan, sealing Malabar’s inclusion in the British Empire. This process was not unmade by later pro-tenant amelioration, which simply sought to increase the contractual bargaining power of tenants within the existing colonially imposed system. Of course, this social change was, broadly speaking, replicating what was done in Ireland in the early modern period in the forms of surrender and regrant, composition, plantation and forfeiture. Indeed, this was a translation, in colonial conditions, of the great enclosure movement that shaped modern England. The main impetus for the resistance of the Whiteboys was grievance against the turning of land into a commodity that would go to the highest bidder, but these transformations in class relations had local beneficiaries and local collaborators. Thus we can have someone with a Gaelic surname wash up on the shores of the Arabian sea to manage a colony there, and thus the first history of the 1921 Malabar rebellion was written by an Indian and dedicated to an Irish British Army officer.

Upon disbandment in 1922, the rank and file of the 1st Battalion Leinster Regiment were of the lowest stratum of Irish society—described in the records as labourers, general labourers or farm labourers—and frequently only temporarily or precariously employed. Skilled tradesmen were only very exceptionally present in the ranks, and farmers were totally absent. For much of the nineteenth century the British Army was disproportionately Irish, as were the European units of the East India Company. For Marx, though, the presence of so many Irishmen in British uniform was not the antithesis of understanding Ireland through a colonial framework but in fact a facet of colonialism. It was the colonial underdevelopment of Irish society that spurred migration to Britain’s armies and factories: ‘Ireland is at present only an agricultural district of England, marked off by a wide channel from the country to which it yields corn, wool, cattle, industrial and military recruits’.

Insurrection in 1921

The roots of the 1921 rebellion lay in the intersection of the India-wide Khilafat and Non-Cooperation movements with local indigenous traditions of resistance. The Non-Cooperation movement was a campaign of boycott directed by the secular nationalist Congress Party, while the Khilafat movement was a Muslim protest concerned with the status of the Ottoman Empire. In early August there were two local incidents—a major mobilisation against a landlord and the gathering of a crowd to prevent the arrest of people accused of assaulting alcohol traders. For several weeks the State authorities relinquished control over the affected area of the rural interior.

On 20 August 1921 there was to be a major raid on a town called Tirurangadi, with the intent of arresting suspected dissident leaders. The military component of the raiding party was 80 men from the 1st Battalion Leinster Regiment. According to the official report, as part of the attempted round-up the Kizhikkapalle mosque was entered by Muslim police officers who beforehand removed their boots, while the more significant Mambram mosque was not targeted at all. Nonetheless, the rumour started—rightly or wrongly—that the mosques had been attacked, particularly the Mambram mosque, which was of special significance, and by mid-day large crowds were clashing with government forces in both the centre of the town and its western outskirts. In the altercation two British officers were killed—one of the Indian police and one of the Leinster Regiment. Outnumbered, the British had to retreat. The nearest railway station had been sacked and the sleepers torn up, so the Crown forces gingerly made their way down the railway line before they could get a train back to their base in the coastal city of Calicut. Consequently, government forces in Malappuram were cut off. The cruiser HMS Comus was dispatched to Calicut to free up the troops there for a relief column to be sent to Malappuram. The column of Leinsters set out on 24 August and had a major clash with rebels at Pookkottur, the site of the 1 August anti-landlord demonstration.

On 31 August an expedition of the Dorsetshire regiment retook Tirurangadi, having marched from the north-east—the opposite direction from the Leinsters. (Incidentally, another Dorset battalion was at this time stationed in Derry, where they made a notably partisan intervention in that city’s communal strife in 1920.) After these instances of open conflict, a pattern of guerrilla warfare set in for the next few months, typified by attacks on isolated police posts and on Hindu landlords, and the destruction of telegraph posts and the blocking of roads and railways.

Above: ‘I do not see why the moplah should be allowed his war knife while the Irishman is prevented from having his pike’—Henry Valentine Conolly in 1844. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY)

Bottom: Mappila (‘moplah’) rebels captured after the suppression of the rebellion by British forces, including the Leinster Regiment, in 1921.

Towards the end of October, a drastically more repressive State policy was adopted, something that seems to be related to the visit of civil servant and TCD graduate Sir William Vincent. Violent repression began with the Dorsets’ punitive expedition to Melmuri on 25 October 1921. During this incident 246 people were killed, according to official figures, and, in the words of historian Conrad Wood, ‘dwellings were burnt wholesale and widespread slaughter of the Moplah population, including an unknown number of those who were not active rebels, occurred’. An additional factor in the suppression of the insurgency was the introduction of élite Nepalese, Indian and Burmese units who were better adapted to the conditions of forest and mountain than the European troops. The other comparatively well-known atrocity occurred on 10 November 1921, the so-called ‘Wagon Tragedy’ in which 64 of approximately 100 captured rebels or suspected rebels imprisoned in a closed railroad wagon died of suffocation. Altogether tens of thousands surrendered—something which underscores the reality of collective punishment.

At the time, the leadership of the Indian nationalist movement dismissed the Malabar revolt as a sectarian jacquerie. It was not until many years afterwards that it received recognition, in a later context of popular mobilisation in the 1960s and 1970s. Similarly, the labour and agrarian dimensions of Ireland’s revolution still get little attention, being passed over in favour of high politics and military confrontation. Likewise forgotten is Ireland’s other contribution to the world revolutionary wave of 1917–23, namely the provision of soldiers to British counter-insurgency. In 1919–21 the 2nd Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers were first in Constantinople (Istanbul) and afterwards in India. The 2nd Battalion Royal Munster Fusiliers were in Cairo, Egypt, while the 2nd Battalion Royal Irish Rifles and the 1st Battalion Royal Irish Fusiliers were in Mesopotamia (Iraq), with the Royal Irish Fusiliers staying to fight the Red Army on the shores of the Caspian Sea. As well as the Leinsters and Dublins, also stationed in India were the 1st Battalion Connaught Rangers, the 2nd Battalion Royal Irish Regiment and the 1st Battalion Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. The Irish revolution was one part of a global revolution.

Terry Dunne has a Ph.D in Sociology from Maynooth University and podcasts at peelersandsheep.ie.

FURTHER READING

C. Wood, The Moplah Rebellion and its genesis (New Delhi, 1987).