The Irish Revolution and the Basque nationalist movement, 1916–23

Published in Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2020), Volume 28The 1916 Easter Rising proved to be the spark that ignited the tensions within Basque nationalism.

By Kyle McCreanor

Above: Sabino Arana—founded the Basque Nationalist Party in 1895.

Historians have recently taken a greater interest in the global context of the Irish revolutionary period (1913–23) and in its international reverberations, which were felt even in the Basque Country, a region straddling the Western Pyrenees on the Franco-Spanish border. This area is home to an ancient, pre-Indo-European people now under the jurisdiction of the Spanish and French states. The Basque Country offers us a clear example of how different episodes of the Irish Revolution were variously interpreted by and affected other contemporary nationalist movements in Europe.

The late nineteenth century marked the birth of a new political player in the bustling industrial port city of Bilbao, with dramatic effects on the future of Spain’s Basque provinces. A young man named Sabino Arana founded the Basque Nationalist Party in 1895, originally aiming not to restore the regional autonomy that had been lost over the course of the nineteenth century but to create an independent Basque state. This was a radical departure from the demands of another movement firmly rooted in the Basque Country—Carlism. The backward-looking Carlists supported a more conservative royal line in Madrid that would restore the social and economic privileges once enjoyed in the Spanish Basque Country.

In the early Basque nationalist press, the Irish Home Rule movement featured among several other examples of foreign nationalist movements to be emulated. Sabino Arana’s fringe movement wrote a letter to Richard McCoy, the nationalist lord mayor of Dublin, in 1897: ‘Basque people lament like Ireland [the] loss of their liberty. […] We send hearty salute[s] through you to [the] noble and courageous people of Ireland.’ Throughout the 1890s, numerous articles in their daily publication extolled the virtues of Irish nationalist icons such as Daniel O’Connell and Charles Stewart Parnell, calling for the Basque people to follow their patriotic example.

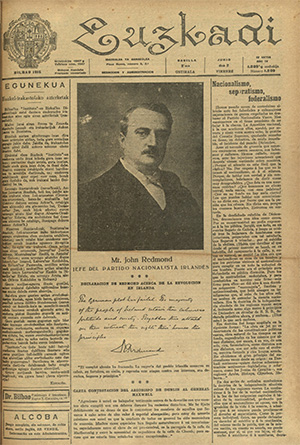

Above: Euzkadi, newspaper of the moderate Basque Nationalist Communion and in 1916 the most widely read in the Basque Country, featured on its front cover this photograph of John Redmond and his statement denouncing the Easter Rising.

Basque–British relations

While the idea of outright independence was at the time relatively radical, Arana’s Basque Nationalist Party did not call for violent subversion of the Spanish state. Hence they admired the legalist Irish Home Rule movement rather than physical-force republican organisations such as the Irish Republican Brotherhood. At the same time, however, there was a strong current of Anglophilia within Basque nationalism. Basque nationalists had a long-standing appreciation for Great Britain as a shining example of virtuous and tolerant government, and the English were readily represented as natural enemies of the Spanish, making them potential allies. Indeed, Basque nationalists at times whitewashed British imperialism and selectively focused on more positive aspects of its history, in contrast with the worst aspects of Spanish rule. Furthermore, the strong British presence in Bilbao’s flourishing steel industry deepened the relationship between Britain and the local Basque economic élite, some of whom would join the ranks of the Basque Nationalist Party.

Ironically, as Irish nationalists sought to distance themselves from Britain, some Basque nationalists envisioned a Basque state as a British protectorate. In 1902 Sabino Arana wrote that ‘the independence of the Basque Country, under the protection of England, will be a happy fact in the not-too-distant future’. In prison for rebellion, Arana died in poor health in 1903. One of his final policy changes proved to be the most controversial: he had moved away from separatism and argued that the Basque Nationalist Party should focus on attaining regional autonomy within Spain. His death split the movement in two, with the more popular section following the more realistic goal of autonomy and the other staying the original course, believing that Arana had probably been compelled while in prison to renounce the cause of independence.

Basque nationalist factionalism and the 1916 Easter Rising

The moderate autonomists quickly assumed control of the Basque Nationalist Party, and tensions continued to grow between them and the smaller but still significant ‘orthodox’ or ‘radical’ independence faction. In 1913, as the Irish Volunteers first began to mobilise, the Basque autonomists started informally to refer to the Basque Nationalist Party as the ‘Basque Nationalist Communion’, signifying their departure from the original doctrine of Sabino Arana and casting it as a mass movement rather than simply a political party (evidently similar to what Sinn Féin would become in the near future). The party’s official press organ, Euzkadi, lauded the British in the First World War, proclaiming that all parts of the Empire were ‘turn[ing] freely and spontaneously to help their mother!’ Meanwhile, the radical separatist faction supported the Germans. In 1916 the party’s change of name to ‘Basque Nationalist Communion’ was made official. The Basque Nationalist Party as such was no more, and the stage was set for a serious confrontation within the movement.

The events of Easter Week 1916 in Dublin proved to be the spark that ignited the tensions within Basque nationalism. Basque radical nationalists sided with the Irish republican rising against British rule; one apocryphal anecdote tells how the young Basque nationalist Eli Gallastegi, chief among the ‘radicals’, organised an abortive volunteer expedition to Dublin to join the rising. Their more numerous moderate autonomist rivals echoed the narrative of the British government and the Irish Parliamentary Party. The daily newspaper of the Basque Nationalist Communion denounced the Easter Rising, along with those Basques who supported it. The newspaper’s director, moderate nationalist Engracio Aranzadi, wrote: ‘That there are Basque nationalists who applaud the fenian movement condemned by Redmond and his 80 deputies is incomprehensible’.

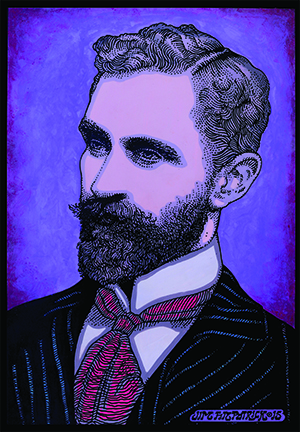

Above: Roger Casement—radical Basque nationalists (a minority) offered Mass for Casement after his execution in August 1916. (Jim Fitzpatrick)

The pro-republican ‘Aberriano’ movement

The debates within Basque nationalism over the Easter Rising came to a head when Aranzadi defamed the recently executed Patrick Pearse and Roger Casement. The radical Basque nationalists, who had offered Mass for Casement after his hanging in a London prison, were incensed by the defamatory articles. Eli Gallastegi, at this point the staunchest Hibernophile within the movement, demanded a retraction of the articles in question, which was promptly rejected. This small faction of adherents to the separatist orthodoxy founded their own weekly newspaper, called Aberri (Fatherland). The pages of Aberri carried strong support for the republican movement, featuring articles on Irish history and short biographies of the most notable martyrs of 1916.

Those involved or aligned with the Aberri publication were known as ‘Aberrianos’ and were in part defined by their support for Irish republicanism. They were somewhat ahead of their time, for, as happened with public opinion in Ireland, most Basque nationalists only developed a serious sympathy for the Rising in the years that followed. With the explosive growth of Sinn Féin in 1917 and its overwhelming victory in the general election of 1918, the Basque Nationalist Communion echoed the mood in Ireland and refrained from denouncing the republican movement as they had done earlier. Nonetheless, they maintained their Anglophilia by focusing their negative attention on Ulster unionists rather than on the British government.

When the War of Independence broke out in 1919, the Basque Aberrianos were surely some of the most zealous supporters of the Irish war effort that one could find in Europe. This faction, finally expelled from the Basque Nationalist Communion in 1921, founded a new political party, reclaiming the old name of the Basque Nationalist Party. No longer constrained by the moderating impulses of the Communion, they lauded the Irish Republican Army with vigour in the final stages of their war with the British. ‘LONG LIVE FREE IRELAND!’ was the call that concluded some of their articles.

Early Basque–Irish contacts

Dáil Éireann’s diplomatic efforts in Spain also began in 1921. Their press agent, Máire O’Brien, sent copies of the Irish Bulletin to one of the heads of the Basque Nationalist Communion, but it is not clear whether she had any contact with the smaller but more supportive Aberriano faction and their newly reconstituted Basque Nationalist Party. O’Brien studied copies of Euzkadi, the rather Anglophilic newspaper of the Basque Nationalist Communion, yet seems not to have known of Aberri. Had their knowledge of local politics been better, the Irish propagandists might have benefited from developing a relationship with their ardent supporters in the Basque Country. At the same time, the British embassy in Madrid wrote back to London exasperatedly that ‘there is undoubtedly constant communication between the sinnfeiners and the separatists in Catalonia and the Basque provinces, and nothing we can do to stop the separatist press in these two regions from publishing anti-English articles’.

Above: Ambrose Victor Martin (front row, second from right) at a Sinn Féin meeting in Dublin after 1916. (Barra McFeely)

The most significant contact of this period was brought about by an informal visit to the Basque Country in 1922 by a young Irishman named Ambrose Victor Martin. Martin was born in Argentina in 1901 to an Irish immigrant family and was sent off to school in Ireland in 1914. He became involved with Sinn Féin after 1916 but was deported to Argentina in 1919, before the outbreak of the War of Independence. Upon hearing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, Martin began his journey back to Ireland but made a detour to the Basque Country. The evidence suggests that he had grown up alongside the Basque immigrant community in Argentina and developed strong ties with them, perhaps even learning some of their notoriously difficult language. Primarily, his visit in Bilbao was for the purpose of visiting old friends, but the Irish-loving Aberrianos arranged for him to give a series of lectures on the Irish struggle for freedom.

Martin relayed to large crowds of eager Basque nationalists the history of the republican movement and laudatory accounts of the Irish Republican Army. Most notably, he gave the inaugural speech for a Basque nationalist women’s organisation inspired by Cumann na mBan. Ambrose Martin’s visit invigorated the audience of young Basques; Aberri reported that ‘never before have we seen our patriotic youth as impassioned as last Saturday, fascinated by the fiery speech of the most eloquent Irish orator’. This visit also sparked a strong and long-lasting friendship between Ambrose Martin and Eli Gallastegi that would greatly shape the course of Basque–Irish relations in the following decades. Afterwards, the young Martin returned to Ireland and quickly became involved with the anti-Treaty republicans in the Civil War.

The Irish Civil War spawned uncomfortable silences within Basque nationalism, just as it would within Irish nationalism. Neither moderate nor radical Basque nationalists took a strong stance on the conflict or discussed it much, but Gallastegi, the most prolific Basque nationalist writer on all things Irish, saw it as a bad omen. Observing many of the same tensions within Basque nationalism over the question of what degree of independence or autonomy ought to be pursued, he predicted a Basque civil war in the future: ‘Spain, one day, will concede ample autonomy to Catalonia, Galicia … to the Basque Country as well. The “unionists” will form a Basque army of “regulars” armed by Spain, with whom they will fight by blood and fire, without mercy, against the “Basque separatist rebels”.’ The imagining of such Basque–Irish parallels indicates the degree to which thinkers like Gallastegi saw the two nations as similar, which made Ireland the most important foreign example for their careful attention.

The relationship between the Basque and Irish nationalist movements progressively deepened in the years that followed this period, but it was the Irish Revolution, with all its triumph and tragedy, that remained the object of fascination for Basque nationalists. As many Basques travelled to Dublin over the years in pilgrimage-like visits, including the future first Lehendakari (president) of an autonomous Basque Country, we can imagine that some stood in front of the General Post Office pondering their own political futures.

Kyle McCreanor has an MA in History from Concordia University, Montreal.

FURTHER READING

D. Keogh, Ireland and Europe, 1919–1948 (Dublin, 1988).

G. Keown, First of the small nations: the beginnings of Irish foreign policy in the interwar years, 1919–1932 (Oxford, 2016).

C. Watson, Modern Basque history: eighteenth century to the present (Reno, 2003).