THE IRISH LAND COMMISSION RECORDS, 1881–1992—A CASE FOR THE DIGITISATION OF THEM ALL

Published in Issue 6 (November/December 2022), Platform, Volume 30By Terence Dooley

First established under the 1881 Land Act, the Irish Land Commission began as a regulator of fair rents but soon evolved into the great facilitator of land transfer. However, over-emphasis on these aspects of its work can sometimes camouflage its equal significance as the main instigator and architect of rural reform. There is no doubt that for most of its existence from 1881 to 1992 the Land Commission was the most important State body operating out of rural Ireland, where its long tentacles spread into every nook and cranny.

Even though the Land Commission has been dissolved for 30 years, however, its archives have not yet been opened to the research public (except on an extremely limited basis). The anomaly of this is difficult to explain, and the loss to Irish historical research is greatly to be lamented. If nothing else, the stymied access has obstructed historians (and, indeed, scholars from a wide variety of other disciplines, including, but not exclusively, Geography, Sociology, Anthropology and Political Studies) in fully appraising countless topics, from the most rudimentary, such as the importance of the everyday work of the Land Commission, to the more complex analysis of any intersection between land and politics. Simply put, the denial of full access to the Land Commission archives prevents the writing of the definitive history of modern Ireland in all its dimensions—social, economic, political and cultural.

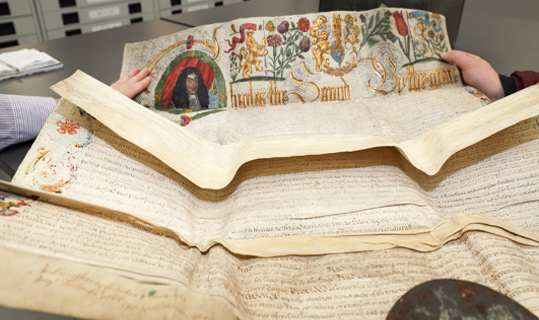

Above: Vellum charter from the reign of King Charles II. This document is a reminder that some of the records in the Irish Land Commission archive date back to the seventeenth century and were inherited from bodies such as the Board of First Fruits and the Church Temporalities Commission. (Alf Harvey)

At the peak of its operations in the 1930s—in terms of acres acquired and redistributed—the Land Commission employed in the region of 1,350 people, making it the largest State agency in Ireland. It was divided into several branches or sections and, while these branches were refashioned from time to time to cater for changing circumstances, the principal ones remained the same. Its work generated an enormous archive. It is estimated that there are around 35,000 individual estate boxes alone containing deeds, valuers’ maps and general descriptions of lands. In relation to local infrastructure and topography, valuers’ reports not only describe individual holdings and their buildings but also provide detail on local markets, transport facilities and local agricultural practices. As regards social history, inspectors’ reports are hugely informative: for purposes of the division of an acquired estate, a Land Commission inspector was sent to an area to gather all the facts he could about each prospective allottee. Each applicant was interviewed to determine the number in his family (making the reports a genealogical source of some significance); the amount and type of stock that he held; and evidence of the capital available to him to invest in any future holding. Potential allottees, it seems, often revealed as much about their neighbours who were in competition with them as they did about themselves. If nothing else, a history of gossip might be extracted from them!

Space here prevents a more detailed discussion of all the Land Commission records now held safely in a repository in Portlaoise, but suffice it to say that in their totality they are a unique source that provide information on everything from who owned/owns the land of Ireland to the ideological philosophies of rural reform promoted by the major political parties of the day. The records enlighten us on the shaping and redesign of physical and, indeed, mental and cultural landscapes. They map the transfer of lands and the creation and disappearance of designed landscapes around ‘Big Houses’; they inform on the reasons for agrarian agitation and litigation, on the migration of smallholders from west to east after independence, and on the flight from the land when small-farm life became unviable after independence. They can reveal much about rural poverty and hardship, social inequality, the lives of women and children, and the lengths some families went to in order to retain ownership of their farms, and they have the potential to add a whole new layer of complexity to our understanding of how the Irish revolution of 1920–3 played itself out in the decades that followed.

As newspaper reports testify, post-independence rural Ireland was seething with frustration, local jealousies, bitterness and anger as lands were divided. There is much work to be done on the extent to which the Land Commission, arguably the body with the greatest power to enact revolutionary social change, embraced that potential, or did it simply become another pawn of local élites? Once opened to the public, assiduous researchers with an eye for the forensics of redistribution patterns may reveal hidden depths of political corruption practised in Ireland over generations, providing, of course, that there has been no culling of the records.

And finally, but no less importantly, the records are of immense value as genealogical sources for both local communities and the diaspora. That means, by extension, that they have huge potential to offer the heritage and tourism industries, so perhaps it is not just one department—Agriculture—that should be responsible for the massive project that would be the digitisation of the records. Rather it should be an inter-departmental mission, including Heritage, Tourism, Arts and the Gaeltacht (after all, the Congested Districts Board records are very heavily focused on traditional Gaeltacht areas), and perhaps the records could even be used to inform portfolios that include Environment, Climate, Food, the Marine, Rural and Community Development, for we have arrived at a moment in time when abandoned historical practices may very well be of value in relation to dealing with current environmental problems. In summation, there is no end to the Land Commission’s historical footprint or, indeed, the potential of its records to inform the present and plan for the future.

For over twenty years this author and others have been campaigning for the opening of the records, and there is a growing ground swell of support for the same. In January 2022 the government’s intention to digitise the records was announced in the Irish Times. Minister for Agriculture Charlie McConalogue TD said that he had set aside €100,000 to begin the process of digitising the ‘search aids’. Some historians and genealogists got ‘excited’ on social media, and perhaps rightly so that a step in the right direction was being taken, but all the key search aids in the world are useless if the records themselves are not then accessible. Imagine what would have been the consternation of the historians of the revolutionary period, who over the last decade or so have greatly reappraised our understanding of 1920–3 through the release of the Bureau of Military History records, if they had been told: ‘We have just digitised these wonderful indexes revealing who was involved in the War of Independence and Civil War but you are not allowed to see the actual witness statements or the IRA pension files’.

In conclusion: the Land Commission generated records to provide the richest social history of the country for a period of over 100 years, reaching from the beginning of the Land War to the decades beyond Ireland’s entry to the European Economic Community (not overlooking the fact that the archive also contains the records of the Church Temporalities Commission, which, after the passing of the Irish Church Act in 1869, took charge of the Church of Ireland’s property, and therefore the archive also includes the records of its predecessor, the Board of First Fruits, founded in 1711). These are the records that document the modernisation of Ireland, that some might argue reveal its very soul. They are at least as important as the records of the revolutionary period, which have rightly benefited from huge capital and personnel investment in the last decade or so. After all, the Land Commission affected far more lives than the War of Independence and Civil War put together.

It is a fact that many records have already been lost. It seems that these include the tens of thousands of letters received annually by the Land Commission from members of the public. They are not in the archives in Portlaoise and a query to the Department of Agriculture as to their whereabouts received the following reply in March 2022: ‘The Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine does not hold records of correspondence of the type referred to by the requestor’. While every effort is now being made to protect the surviving records under appropriate conditions in the Land Commission offices in Portlaoise, some are already in a fragile condition, and this surely points to the need to digitise them all as a matter of urgency. There is no escaping the fact that it will be a monumental task, but surely we cannot have the equivalent of what happened to the Four Courts records in 1922, except this time from government lethargy?

Terence Dooley is Professor of History and Director of the Centre for the Study of Historic Irish Houses and Estates at Maynooth University.