The Irish ladies of Llangollen: ‘the two most celebrated virgins in Europe’

Published in 18th-19th Century Social Perspectives, Features, Issue 6 (November/December 2015), Volume 23WOMEN WHO BROKE AWAY FROM THE RESTRAINTS OF CONVENTIONAL LIFESTYLE, THEIR SEX AND THEIR CLASS

By Eugene Coyle

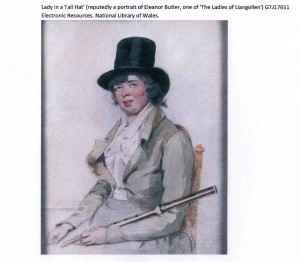

Left: Pen and ink drawing of Lady Eleanor Butler (1739–1828), sketched c. 1765. (National Library of Wales)

In the early summer of 1778 two Anglo-Irish women, accompanied by their maidservant, fled from Kilkenny and arrived in north Wales. They were dressed as clergymen and their maidservant as a boy. Who were they, and why the unconventional dress?

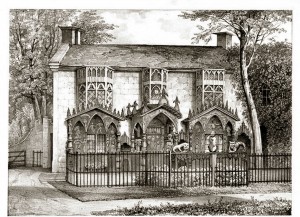

The women were Eleanor Butler of Kilkenny Castle and Sarah Ponsonby of Woodstock House, Inistioge, both later described by the visiting German Prince Pückler-Muskau as ‘the two most celebrated virgins in Europe’. They declared that they wished to live in ‘delightful retirement and seclusion’ and devote themselves to self-improvement, gardening and farming. In their own lifetime these Anglo-Irish ladies became something of a cause célèbre, attracting a long list of admirers, from royalty and politicians to soldiers, inventors, philanthropists, actors, scientists, artists and poets. Their home, ‘Plas Newydd’, was transformed into a Gothic fantasy of projecting stained glass heavily furnished in elaborate carved oak. The Rousseauian landscape was picturesque, with extravagantly designed gazebos and water features.

Place of pilgrimage

Many well-known figures from eighteenth-century Irish and English society made ‘pilgrimages’ to Plas Newydd. Princess Caroline, wife of the prince of Wales, visited and organised a small pension for them. Anglo-Irish politicians Lord Charlemont, William Brabazon Ponsonby, Lord Castlereagh, Lord Chancellor John FitzGibbon and the revolutionary Lord Edward FitzGerald all visited Plas Newydd. Arthur Wellesley, duke of Wellington, became a frequent visitor and placed the ladies on the civil list. From the world of literature the poets William Wordsworth, Robert Southey and Lord Byron dedicated poems in their honour. Novelists Sir Walter Scott and Lady Caroline Lamb (née Ponsonby) were also their guests. Figures from the world of science and philosophy, Erasmus Darwin and his son Charles, visited; Josiah Wedgwood lectured them on rock formations. Playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan and the actresses Sarah Siddons and Dorothy Jordon, mistress of the duke of Clarence, were also their guests.

William Wordsworth celebrated the ladies in a sonnet, ‘Sisters in Love’; the painter and poetess Anna Seward wrote poems about their ‘Davidean friendship’ and painted portraits of them; Anna Lister (1791–1840), a nineteenth-century diarist who supported the lesbian lifestyle, wrote in 1822: ‘… I cannot help thinking that surely it was not Platonic. Heaven forgive me, but I look within myself and doubt.’ Diarist Mary Elizabeth Lucy recorded: ‘… these two ladies looked just like two old men … they were so intensely devoted to each other that they made a vow, and kept it, that they would never marry or be separated, but would always live together … never leave or sleep out for even one night.’

A late Victorian photograph of an original miniature (now lost) of Sarah Ponsonby (1755–1831). (National Library of Wales)

Romantic friendship in north Wales

There has been considerable debate, during their lifetime and after, on the nature of the relationship between the two ladies. Suspicion of lesbianism circulated among their visitors, and reports occasionally appeared in the English and Irish press. The Anglo-Irish women shared bed, board, books, income and daily walks; they dressed similarly in men’s waistcoats while wearing women’s skirts, although Eleanor tended to be more masculine and Sarah more petite and feminine; they signed all their correspondence jointly. A succession of their pet dogs were named ‘Sappho’.

Their love affair was described as a ‘romantic friendship’, a vague, ambiguous term used in literature to describe the love between women living together in friendship. Samuel Richardson’s influential Clarissa, or The history of a young lady promoted the concept of ‘romantic friendship’ in which the heroines had made a pact to act as each other’s moral guardians and to live together rather than marry. Maria Edgeworth satirised the ladies of Llangollen in her Moral tales, published in 1801. Her novel Angelina, or L’amie inconnue was based on the Kilkenny ladies’ elopement and their subsequent notoriety and celebrity status in Wales. It warned about the moral and social dangers of close female relationships and the fantasy worlds of romantic novels.

Background

Eleanor Butler was born in 1739 at Cambrai, Nord-Pas-de-Calais, into an Irish Catholic aristocratic family and was a lineal descendant of the duke of Ormond, James Butler. As a Catholic gentlewoman, Eleanor was educated at the English Benedictine Convent of Our Blessed Lady of Consolation at Cambrai and received a liberal French education for the first eighteen years of her life. She lived at Kilkenny Castle from the 1750s to 1778 under a bad-tempered dominating mother and an indifferent father.

Sarah Ponsonby was born into an Anglican Ascendancy family in Dublin in 1755, the only daughter of Chambré Brabazon-Ponsonby, Irish MP for Newtownards. Her life in Kilkenny had many parallels to the melodramatic and romantic novels of Samuel Richardson or Henry Fielding. Orphaned in 1768, the naive and penniless thirteen-year-old Sarah was placed as a boarder in Miss Parkes’s school in Kilkenny under the guardianship of her late father’s cousin, Lady Elizabeth (Betty) Fownes of Woodstock Hall, Innistioge. Sarah was a tall, graceful girl who spoke and understood French and Italian, and sketched well from nature.

Eleanor Butler, who was twice her age, was appointed her tutor. The impressionable Sarah and the older, domineering Eleanor became inseparable friends and over the next six years exchanged a secret and intimate correspondence. This did not go unnoticed, however, as malicious gossip about their close personal relationship circulated among the close-knit gentry in the salons and ballrooms of Kilkenny and later at Dublin Castle.

Plas Newydd cottage c. 1790—became a place of pilgrimage for many well-known personalities from eighteenth-century Irish and English society. (National Library of Wales)

Elopement from Kilkenny, 1778

In 1773 Sarah, then aged eighteen, left Miss Parkes’s finishing school and entered Irish Ascendancy society as a debutante. Her guardians, the Fownes family at Woodstock, were anxious to find a suitable rich husband for her as soon as possible, as she had no dowry. There was also a major problem: her rich and powerful guardian, Sir William Fownes, had ‘persecuted her with his unwelcome attentions’ and there was an allegation of an attempted rape.

In the meantime, Eleanor Butler was facing an ultimatum from the Butler family at Kilkenny Castle. She was nearly 40 and had spurned several marriage alliances. The Butler family had become alarmed at her intense relationship with Sarah Ponsonby and in order to suppress scandal they had made arrangements for her to enter a French convent near Calais.

On 30 March 1778, rather than face the possibility of being forced into unwanted marriage or, worse still, a convent, Eleanor and Sarah decided to abscond and live together in England. They travelled on horseback to Waterford, dressed as men and armed with pistols. Eleanor’s father, with some of his own servants and Captain Wymms of the Kilkenny Volunteers, pursued them to Waterford. Here the women were caught and ignominiously returned to Kilkenny as prisoners.

Over the next few weeks both families tried to persuade them to give up their liaison and return to society. Sarah’s health condition was feverish and worsened, while Eleanor was placed under ‘house arrest’ at her sister Susanna Kavanagh’s house in Borris until a place in a convent at Calais could be found for her. Lady Fownes, Sarah’s guardian, wrote:

‘We hear the Butlers will never forgive their daughter and that she is to be sent to France to a convent. I wish she had been safe in one long ago; she would have made us [all] happy. Many an unhappy hour she has cost me, and, I am convinced, years to Sally [Sarah].’

Eleanor escaped and was hidden in Sarah’s bedroom at Woodstock House. Over the next few weeks, negotiations between the women and the two families broke down. In the end, however, the Butler and Fownes families reluctantly agreed to the women’s demands. The agreement was reached on condition that they would live abroad and never return to Ireland. In return they were granted small allowances.

Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby travelled from Waterford to Milford Haven with their faithful servant, Mary Carryl. The journey involved a potentially dangerous crossing, as the Irish Sea was patrolled by squadrons of heavily armed American, Irish and French privateers. They arrived safely in Wales, however, and wandered aimlessly about for some months, finally arriving at the small village of Llangollen in September. Over the next two years they rented a number of houses, eventually in February 1780 moving into the cottage overlooking the village and renaming it Plas Newydd. Here they spent the rest of their lives openly together and never returned to Ireland. The ladies in their lifetime gained substantial notoriety, excited much curiosity and became controversial literary subjects, two courageous and audacious Irish women who broke away from the restraints of conventional lifestyle, their sex and their class.

Eugene Coyle is a retired independent history scholar and a sessional tutor at Oxford University Department of Continuing Education.

Further reading

C.J. Hamilton, Notable Irishwomen (Dublin, 1904).

E. Mavor, The ladies of Llangollen: a study in romantic friendship (London, 1971).

L.A. O’Donnell, ‘An extraordinary affair’, RTÉ podcast, 30 April 2011, https://ladiesofllangollen.wordpress.com.

Read More: Public Attitudes