The Flight of the Earls: escape or strategic regrouping?

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Gaelic Ireland, Issue 4 (Jul/Aug 2007), Volume 15Four centuries ago on the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, 14 September 1607, an unnamed 80-ton French warship weighed anchor at Rathmullan, Co. Donegal, and sailed out of Lough Swilly for La Coruña, Spain. Among the 99 persons on board were Hugh O’Neill, second earl of Tyrone, recently restored to his earldom, Rory O’Donnell, recently created earl of Tyrconnell, and Cuchonnacht Maguire, with their families, servants, soldiers and mariners.

Who was on board?

Apart from the Gaelic Ulster nobility, who else was on board that ship? And who was left behind? Among the secretaries and writers on board, apart from the diarist Ó Cianáin, were Matthew Tully, the erstwhile secretary to Red Hugh O’Donnell, who had gone to Spain after Kinsale seeking more military aid but who died in Simancas Castle, near Valladolid, in 1602. The celebrated Irish bard Eoghan Rua Mac an Bhaird accompanied his patroness, Nuala O’Donnell, known to history as ‘the lady of the piercing wail’ (from a Clarence Mangan translation of a Mac an Bhaird poem). She had much cause for grief: her husband Niall Garbh O’Donnell went over to Sir Henry Docwra during the last phase of the Nine Years’ War. She had, moreover, witnessed the cruel murder of their infant son at the hands of her brother, Red Hugh. Two chaplains to the O’Neill family were present: Patrick Duff, his private chaplain, and Patrick O’Lorcan, chaplain to his fourth wife, Lady Catherine Magennis, the daughter of Sir Hugh Magennis. Rosa O’Doherty, sister of Sir Cahir O’Doherty and then married to Cathbar O’Donnell, Rory O’Donnell’s brother, was there; she later became the wife of Hugh’s nephew, Owen Roe O’Neill.

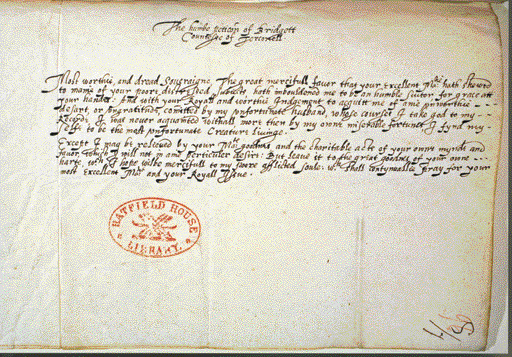

The earls’ retinue included children and infants, notably Seán, ten-year-old son of Hugh O’Neill, and his brother Brian or Bernard, who years later died in suspicious circumstances in Brussels (hanged with his hands tied behind his back) and was buried in St Anthony’s, Louvain. There were also two Hugh O’Donnells: one the infant son of Cathbar and Rosa, the other the one-year-old baron of Donegal, son and heir to Earl Rory. After his father’s death in 1608 the latter Hugh would become the titular second earl of Tyrconnell. He later drowned in the Mediterranean while fighting for Spain against the French in 1642. Rory left behind his teenage wife and Hugh’s mother, Lady Bridget Fitzgerald, daughter of the earl of Kildare. Pregnant at the time of the flight, she remained in Maynooth and was later reduced to making desperate pleas to James I for financial assistance.

Though Ulster patronymics predominate in the rest of the passenger list—O’Hagan, O’Quinn, MacDavitt, Gallagher and McSweeney—a good number of Old English names, largely from the northern Pale/Louth area, were also represented—Bath, Rath, Preston, Moore and Plunkett. Also on board was Richard Weston, a Dundalk-based merchant and double agent, dubbed the ‘manager of O’Neill’s bribes’ in contemporary English state papers. Donagh O’Brien, a cousin of the earls of Thomond and Clanrickard, who had helped Cuchonnacht Maguire to get to Rathmullan, had also joined the throng. Finally, Pedro Blanco, the celebrated Spanish officer who had loyally served O’Neill since surviving the 1588 Armada shipwreck, and who distinguished himself at the Yellow Ford and Kinsale, also accompanied his master. The crew comprised French, Spanish and Flemish hands.

Who was left behind?

Notable by his absence was Hugh O’Neill’s brother, Sir Cormac MacBaron O’Neill, whose relations with Tyrone had become frayed by the end of the war. He knew of the escape for he accompanied the party to within five miles of Derry but then withdrew. Did Cormac, in fact, harbour ambitions for the earldom of Tyrone? If so, he would have proved a continuing obstacle to the policies and schemes of Sir Arthur Chichester and Sir John Davies. In the conspiratorial climate of the times, it is not surprising that Sir Cormac ended his days in the Tower of London. Another eventual inmate of the Tower, Conn O’Neill, the young son of Earl Hugh and Lady Catherine Magennis, could not be found when they gathered up their children en route to Rathmullan. He became a ward of Sir Toby Caulfield at Charlemont and was later sent to Eton College. When conspiracies stalked King James’s three kingdoms after the Gunpowder Plot, Conn found himself in the Tower, where he most likely died of starvation and neglect in the company of Niall Garbh O’Donnell and his son Nachten, both incarcerated in the aftermath of the O’Doherty rebellion in 1608.

A French warship at anchor off Rathmullan, Co. Donegal, from BBC Northern Ireland’s three-part documentary on the Flight of the Earls

Simancas Castle, near Valladolid, the Spanish royal fortress where Red Hugh O’Donnell died in 1602.

The O’Cahan case

In the circumstances surrounding the flight, perhaps the most cogently proximate cause was O’Neill’s legal wrangling with Sir Donal Ballagh O’Cahan. As his chief urri and son-in-law, O’Cahan enjoyed his ancestral seat at Dungiven, Co. Derry, a site and castle that rivalled O’Neill’s Dungannon abode. O’Cahan’s desertion of O’Neill at a critical juncture in the war, the Mellifont settlement and the subsequent restoration of O’Neill as earl of Tyrone further strained these ancient relationships in the Gaelic polity. Furthermore, an element within the New English administration was determined to roll up the map of the Gaelic lordships and fed O’Cahan’s growing resentment. O’Cahan himself would in turn be accused of treasonable practices in the O’Doherty rebellion and ended his days in the Tower.

O’Neill’s decision to leave Ireland has puzzled contemporaries and successive generations of historians, given the generous terms of his submission at Mellifont in March 1603, his pardon and restoration as earl of Tyrone, and his son’s elevation to the baronage of Dungannon. It became clear to O’Neill, however, that the restoration of the earldoms on paper did not match the realities on the ground in early seventeenth-century Ulster. He complained of having received little more than empty titles. In all explanations of why the earls left, the conspiracy theory looms large. O’Neill had never lost touch with Spain or the hope that Philip III would send succour to continue the war to oust the newcomers and give him proper restoration of his ancestral lands.

Hugh O’Neill-sent either for the great good or the great ill of his people.

In this continuing ‘trafficking with Spain’ (as the government termed it) O’Neill broke his own solemn promises made at Mellifont. To compound the conspiracy theory, it is also contended that the government, especially through the machinations of Lord Deputy Chichester and his attorney-general, Sir John Davies, and Cecil, earl of Salisbury, fabricated treasonable plots against O’Neill, plotted to have him assassinated and aimed at nothing less than the destruction of the Ulster Gaelic lordships.

To that end, O’Cahan’s case against O’Neill played into their hands. How can this be considered a major cause of the flight of the earls? The legal case exposed a saga of breaches of promise. When Sir Henry Docwra pleaded O’Cahan’s cause before Lord Mountjoy and the council, he found that the promises he had made to O’Cahan, confirmed by Mountjoy as lord deputy, could not now be honoured as they were at odds with the restoration and appeasement of O’Neill made at Mellifont. Mountjoy’s reply to Sir Henry in the council chamber is worth citing:

‘To Sir Henry Docwra, sayeth he: “My lord of Tyrone is taken in with promise to be restored as well to all his lands, as his honour of dignity, and O’Caine’s [O’Cahan’s] country is his, and must be obedient to his command”.’

The scene in the chamber was one of high drama as Docwra was there to individually plead the causes of all his Irish allies. Hugh O’Neill was present with Mountjoy. Was this the first time Docwra ever set eyes on his former enemy, on whose head he had placed the price of £2,000? O’Neill’s own reactions are not recorded at this stage of the meeting. Did he remember that this same Donal O’Cahan had saved his life on the field at Clontibret seven years earlier? Conversely, would O’Cahan now regret having done so? A heated exchange ensued, with the trading of mutual insults amidst claims and counter-claims. At one point Mountjoy referred to O’Cahan as nothing more than ‘a drunken fellow’, and would not be moved by Docwra’s more reasonable arguments that they were there to discuss weighty matters and not O’Cahan’s drinking habits. Mountjoy reminded Docwra that what he had done ‘was not without the advice of the council of this kingdom, that it was liked and approved of by the lords in England, by the queen that is dead, and by the king’s majesty that is now living . . . and I am persuaded that it may not be infringed’. Mountjoy dismissed Docwra, swearing that O’Cahan ‘must and shall be under my lord Tyrone and that he had no more to say on the matter’.

Back in Derry, Docwra broke the news to O’Cahan, who flushed with rage and ‘bade the devil take all Englishmen and as many as put their trust in them’. Unable to meet O’Neill’s traditional levies of various black rents and taxes owing to the devastation of his country by the scorched earth tactics of the war, O’Cahan yielded about a third of his ancestral lands west of the Bann to O’Neill, although he received a rebate of lands for an annual rent of 160 cows. This interim measure satisfied neither party, as the castles, used so effectively by Docwra against O’Neill in 1602, remained in government hands. Moreover, O’Neill still claimed that O’Cahan did not hold any land by right but by his grace and favour. In fact, according to the legal historian Frank Harris, the Irish council in June 1607 found that the disputed lands belonged neither to O’Neill nor to O’Cahan. The disputes festered on and became further inflamed by the intervention of George Montgomery, bishop of the combined sees of Derry, Raphoe and Clogher, former chaplain to King James and brother of Hugh Montgomery, the successful planter in north Down. He advised Donal O’Cahan that since he was still married to his first wife, Marie O’Donnell, he should avoid a charge of bigamy by sending Rose O’Neill back to her father, the earl of Tyrone. When she married O’Cahan she was the widow of Red Hugh O’Donnell. In the event of her repudiation O’Neill demanded his daughter’s dowry back. He also sought the return of traditional termon or church lands in the possession of Montgomery.

Legal imperialism

The ramifications of the O’Neill/O’Cahan disputes, as well as the personal animosities of Lord Deputy Chichester and Attorney-General Davies towards Tyrone, created a climate of uncertainty and insecurity among the Gaelic nobility, which was deliberately fostered by Chichester and Davies. Mountjoy’s death in April 1606 removed O’Neill’s chief support at court and council. Davies, a past master at delving into defective titles, prepared a case in English common law to prove that O’Cahan’s lands had been legally vested in the crown. Chichester, on Davies’s advice, also set up ‘a commission to remedy defective land titles’, while Davies’s use of O’Cahan’s grievances clearly undermined O’Neill’s restored status as earl of Tyrone and stifled his attempts to act as a Gaelic overlord. If this case succeeded, O’Neill’s lands would have been reduced to his former lucht tighe—his mensal lands around Dungannon, Donaghmore and north Armagh. Once cut down to size, crown tenants and freeholders could be planted on O’Neill’s remaining lands, following the precedents set in Cavan and Monaghan and parts of Donegal, where the first English-type assizes had been operating since 1604. These arrangements mirrored English law practices; the government endeavoured to dispense with Irish land customs of gavelkind (i.e. partible inheritances), and the judges of the king’s chancery courts deemed all brehon pronouncements dealing with land divisions to be null and void. This legal imperialism, together with the continued promotion of the established Protestant church in the face of Catholic missionary efforts, lay in the background to the events of 1607 and help us to understand why the Gaelic nobility left the country when they did.

‘The humble peticon of Bridgett Countesse of Terconell’-Bridget, daughter of the earl of Kildare, was the pregnant teenage wife of Rory O’Donnell left behind in Maynooth, and was later reduced to making desperate pleas to James I for financial assistance. (Marquess of Salisbury)

O’Neill was in no doubt that crown officials were orchestrating the O’Cahan case to undo him. No wonder he called Davies ‘a stage manager’! Davies and O’Neill had a notable encounter in March 1607, when Davies told him that he hoped to live to see ‘you, my lord, the best reformed subject in Ireland’. O’Neill replied that he hoped from his heart that the attorney-general might never live to see the day when injustice should be done him by transferring his lands to the crown and thence to the bishop. The case was called to the king’s bench in Dublin. O’Cahan successfully petitioned for Davies to act as his counsel, creating a farcical situation whereby the government’s primary legal adviser acted as counsel for one of the contending parties. O’Cahan received loans to pursue his case and, after the preliminary hearing, he was knighted by Lord Deputy Chichester in June 1607. At their meeting in court in May 1607 O’Neill lost his temper, ‘snatching a paper out of O’Cahan’s hand and rending it’ in front of the lord deputy. The case had in fact become a trial of strength between O’Neill and the ministers of the king.

Old English/Gaelic Irish plot?

Meanwhile, Chichester received information (by way of the customary anonymous letter found at the door of the Dublin Castle council chamber) about an Old English/Gaelic Irish plot ‘to murder or poison’ him and which allegedly had the support of Old English and Gaelic Irish Catholics alike. At the same time King James, still amenable to O’Neill, regretted his complaints against the Dublin administration and his troubles with O’Cahan. By mid-July 1607, however, King James’s attitude of conciliation and toleration had dramatically changed to one of menace and hostility. He had been warned of a planned Catholic revolt in Ireland fuelled by Chichester’s anti-Catholicism. Sir Christopher St Lawrence’s revelations (much commented upon by historians) then made plain all the details of the plot.

Historians have been unable to agree on whether or not there was a plot in 1607, considering the unreliability of Christopher St Lawrence, later Lord Howth, who played on both sides. Those who affirm its existence conclude that the earls were in fact fleeing for their very lives, and that if O’Neill had answered the king’s summons to London for the start of the Michaelmas law term (the end of September) he would have found himself in the Tower of London awaiting possible execution. John McCavitt argues that while the government had been following a policy of appeasement towards O’Neill it changed dramatically in July 1607 on foot of Lord Howth’s allegations.

‘The humble peticon of Bridgett Countesse of Terconell’-Bridget, daughter of the earl of Kildare, was the pregnant teenage wife of Rory O’Donnell left behind in Maynooth, and was later reduced to making desperate pleas to James I for financial assistance. (Marquess of Salisbury)

He concludes that O’Neill left the country uncertain of what action King James would take and speculates that in the absence of any clear evidence of O’Neill’s part in a conspiracy James would have adopted his usual and ‘characteristically timorous approach’. On whether there was a government plot against O’Neill’s life the historical jury is still out. The earls failed, however, to adapt to the new regime, with its courts, assizes, the need for freeholders to serve on juries, sheriffs, English common land law tenures and the inevitable whittling away of their ancient Gaelic rights demanded by the new dispensation.

Strategic regrouping?

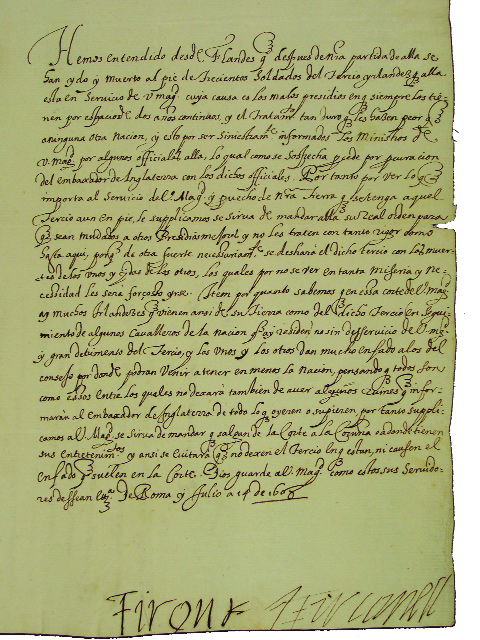

What of the view that there was no ‘flight’ but rather a strategic regrouping of resources to come back to Ireland with Henry O’Neill’s Irish regiment from Spanish Flanders and with money and arms from Spain to regain their ancestral lands, drive out the new arrivals, and rejuvenate and re-establish Catholicism? The persistent fears of the government that O’Neill’s demands in letter after letter from Rome to Madrid in pursuit of those aims would undermine the 1604 peace treaty with Spain are a constant theme in the state papers of the time. The Dublin administration often referred to the O’Neill regiment in Flanders as that dark cloud on the horizon. English ambassadors in Brussels, Venice and Rome and the ever-active network of spies and agents monitored every movement of the earls abroad and kept a close eye on O’Neill in Rome until his death in July 1616. His very presence in Europe had repercussions on diplomatic relations between Spain, Flanders, the Dutch United Provinces, Rome and England. This view of the flight is sustained in Kerney Walsh’s collection of documents from the Continental archives, a selection of which is presented in her celebrated Destruction by peace (Cumann Seanchais Árd Mhacha, 1986). The title is O’Neill’s own succinct summary of his fate.

There are some indications in O’Neill’s correspondence that he may well have considered a tactical retreat or regrouping of his forces but from abroad long before the actual flight from Rathmullan in September 1607. He wanted to go in person to ask Philip III for military aid and to use the Irish soldiery then fighting for the king in the Netherlands. On the anniversary of the defeat at Kinsale, 24 December 1602, he wrote from his retreat in Glenconkeyne requesting Philip III’s help:

Hugh O’Neill’s letter from Rome, 9 July 1608, to Philip III, appealing for assistance.

‘In the name of God, we beg Your Majesty to be moved by the miseries which we suffer and send help to us… since our endeavours and the defence we have made up to the present have been in the cause of religion and in the service of your father and of yourself we pray Your Majesty . . . to send a warship to the northern part of Ireland so that we may be conveyed to you, safe from the fury of our enemies . . . From your most faithful vassal, O’Neill. Glanconkeine, 24 December 1602.’

Philip III, guided by the duke of Lerma and hamstrung by bankruptcy, determined that there would be no renewal of the war with England. Likewise, Olivares, one of Philip’s most trusted counsellors since the Kinsale débâcle, poisoned the king’s mind with the idea that ‘Ireland was always a noisy business and more trouble than advantage to your Majesty’. Moreover, the signing of a twelve-year truce between Spain and the United Provinces presented another major obstacle that put an end to any further hope of Spanish aid to Ireland. O’Neill’s correspondence from Rome, however, gives the lie to the interpretation that he never intended to return. Most historians are not surprised that O’Donnell and Maguire had long wanted to leave and try their fortunes in the Spanish armies. But it is the apparently precipitous departure of O’Neill from Slane that has caused so much speculation. In the Highland Papers there is an intriguing letter of 10 May 1607 from O’Neill to the earl of Argyll (The McQuillan when it suited him), now James’s right-hand man in quelling the McGregors and McLeans in the Highlands and Isles:

‘I have made a motion to your Lordship of matching my son and heir Hugh [then 4th Baron Dungannon] with your daughter but have received no answer as yet. But in future communications on this matter use the good offices of my son-in-law, Sir Randall McSorley McDonnell, who dwells somewhat nearer the coast than I do.’

The Treaty of London (1604) concluded the Anglo-Spanish war, and Philip III, hamstrung by bankruptcy, was determined that there would be no renewal of hostilities with England. (Public Record Office, Kew)

Nicholas Canny holds that O’Neill in 1607 may very well have been settling up his affairs, leaving his son Hugh in charge of his dwindling estates and contemplating retirement to England, thereby throwing himself on King James’s mercy. Subsequent attempts to regain James’s favour, as evidenced by his foreign correspondence, lend some support to this insight. O’Neill’s motives have ever been enigmatic, and his diplomacy Machiavellian—necessarily so to survive. Yet his consistent efforts from Rome, in the midst of the deaths of relatives and companions, to secure aid and return, sword in hand, to regain his lands and set Ireland free from tyranny (and possibly united under the Spanish monarchy) portray a rare heroism that enhances his place in history. His aims may now appear unrealistic; he died in 1616 without achieving them. In Camden’s opinion O’Neill was sent either for the great good or the great ill of his people. Fittingly, the final entry in the Annals of the Four Masters is that for 1616, and is a well-known and more generous eulogy on O’Neill.

John McGurk is Emeritus Professor of History at Liverpool Hope University and Associate of the University of Ulster.

Further Reading:

F.W. Harris, ‘The state of the realm: English military, political and diplomatic responses to the Flight of the Earls’, The Irish Sword 54 (1980).

J. McCavitt, The Flight of the Earls (Dublin, 2002).

J. McGurk, Sir Henry Docwra, 1564–1631: Derry’s second founder (Dublin, 2006).

P. Walsh (ed.), T. Ó Cianáin’s The Flight of the Earls (Dublin, 1916).