The Fenian plot to kill the future King George V

Published in Features, Issue 4 (July/August 2021), Volume 29By Dean Jobb

They wore workmen’s clothing, making them indistinguishable from the thousands of Irish newcomers in search of jobs in Nova Scotia’s mines or building its railways. James Holmes, almost six feet tall, with a dark complexion and a drooping black moustache, had been born in St Joseph, Missouri. His companion, William Bracken, came from somewhere in New York state. They gave the same age, 30, but Bracken looked a couple of years younger. Their accents were so pronounced that one man who met them found it hard to believe that they were not Irish-born. Holmes’s family hailed from County Donegal and the parents of both men no doubt were refugees from the Great Famine.

The men first turned up in Halifax in July 1883 and took a room at a waterfront boarding-house, where they could keep an eye on harbour traffic. Halifax was the Royal Navy’s most important depot on Canada’s Atlantic coast, and the ship they were looking for dropped anchor on 1 August. The cruiser HMS Canada was a steam-and-sail-powered hybrid, with a smoke-spewing funnel that looked out of place amid its three masts. One night, to get a closer look, the visitors hired a small boat and rowed past the warship in the darkness.

Chance discovery

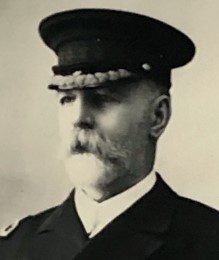

Above: Halifax detective Nicholas Power—discovered the would-be assassins’ cache of dynamite by chance. (Halifax Police Museum)

Holmes and Bracken left the city in mid-September, only to reappear on 12 October to check into the Parker House Hotel. Soon Detective Nicholas Power, an eighteen-year veteran of the Halifax police, dropped by. He was investigating a break-in at a nearby dry goods store and on the lookout for guests acting suspiciously or loitering in the neighborhood. The proprietor mentioned the newly arrived Americans, noting that they ‘slept late into the day and were out late at night’.

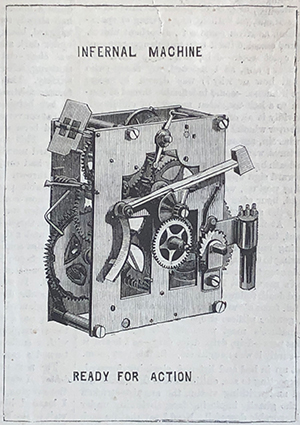

The detective searched their room while they were out and made a shocking discovery. Two suitcases, stashed under a bed, were packed with 100 pounds of dynamite. Each case also contained a small clock and the wires and mechanisms needed to create an ‘infernal machine’—a crude time bomb, and an incredibly powerful one. If detonated, it was explosive enough to level the hotel and every other building on the block.

Holmes and Bracken had come to Halifax on a deadly mission. Their goal was to blow up and sink HMS Canada, killing as many of its crew as possible—including, they hoped, an eighteen-year-old midshipman. He was Prince George, Queen Victoria’s grandson, who would one day ascend to the throne as George V.

Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa’s dynamite campaign

The plot was part of a campaign of terror waged by Clan na Gael, a network of Irish expatriates better known as the Fenian Brotherhood. The Fenians, many of them veterans of the American Civil War, were determined to drive the British out of Ireland; their weapon of choice was dynamite. Patented by Alfred Nobel in the 1860s, it was the perfect terrorist weapon of the time—powerful, lightweight and stable enough to be easily transported. Fenian agents from America brought their struggle to Britain in the early 1880s, planting bombs in Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow, Birmingham and even in the heart of London. Between 1867 and 1887 extremists detonated at least 60 bombs in British cities, killing as many as 100 people in a sustained, well-organised terrorist campaign—one of the first of its kind.

Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, a staunch Fenian and publisher of the New York-based United Irishman, was the alleged mastermind behind the bombings. A skilled propagandist, he knew how to grab headlines and spread fear. ‘I go in for dynamite,’ he stated to supporters of Irish independence at a Brooklyn meeting, confident that the journalists present would amplify his words. ‘Tear down English cities! Kill the English people! It is open warfare.’

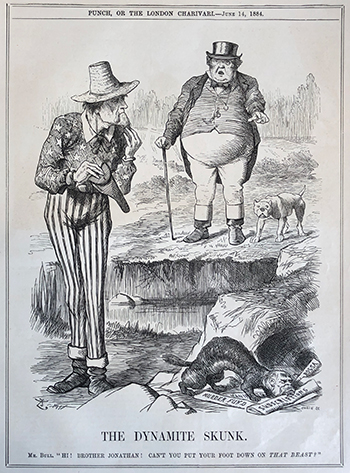

The British government appealed to Washington to crack down on O’Donovan Rossa and other radicals who were inciting violence and raising money to fund terrorism. It also urged the Americans to stop bombers and dynamite from leaving their shores. It was ‘the duty of every civilized government’, Home Secretary Sir William Harcourt told the House of Commons in mid-1881, ‘to co-operate in putting down with a strong hand these nefarious attempts’. But it was not clear what the US could do to prevent its citizens from exporting terror. O’Donovan Rossa and his ilk were not breaking US laws and no crime had been committed on US soil. For the administration of President Chester Arthur, any attempt to deal with Fenian extremism abroad risked a backlash at home. Irish-Americans were a political force, a powerful voting bloc with the numbers to elect or defeat politicians, even presidents.

Britain’s leaders and their sovereign soon became targets. In 1882 a tipster warned the Foreign Office that ‘the lives of your Queen, the Prince of Wales and his sons, indeed of the whole royal family are in jeopardy’. That May, Fenian assassins ambushed and murdered Lord Frederick Cavendish, the chief secretary for Ireland, and his aide in Dublin’s Phoenix Park. The British responded with new security measures and created a counter-terrorism force within Scotland Yard. The famous Pinkerton detective agency was hired to keep tabs on O’Donovan Rossa and other Irish radicals in the US.

Meanwhile, O’Donovan Rossa turned up the heat. While Irish moderates condemned the Phoenix Park murders, he praised Lord Cavendish’s assassins for eliminating ‘the chief agent of the British tyranny and robbery in Ireland’. In private, he continued to plot new bombing missions for his agents. Once, when a reporter for the New York Sun turned up at his office seeking his reaction to the latest dynamite attack, he advised the inhabitants of every city ‘protected by the English flag … to get rid of the protection of that flag as soon as they can’.

Such a city was nearby—Halifax. As the British beefed up security at home and surveillance abroad, the Fenians looked for targets closer to their American base. Canada had been used as a battleground in the Irish campaign against Britain in the past. A small Fenian army had invaded present-day Ontario in 1866 and two years later a Fenian sympathiser had gunned down Thomas D’Arcy McGee, a prominent Irish-Canadian politician and former Young Irelander. The arrival of Prince George in Halifax in 1883 put a member of the royal family within easy striking distance.

Above: Prince George, the future King George V, in uniform during his naval career.

Prince George

George, born in 1865, was the second son of the Prince of Wales, who would ascend to the throne in 1901 as Edward VII. Like today’s Prince Harry, George was not an heir but a ‘spare’—his older brother Prince Albert Victor was next in line. Their father, who viewed naval training as ‘a real and practical apprenticeship to the serious business of royal life’, sent the teenaged brothers on a three-year world tour aboard HMS Bacchante. Shipmates admired George’s skill in the boxing ring and would remember him as a ‘sunny and mirth-loving’ companion who never took advantage of his privileged status.

George remained in the navy when Albert was sent to Cambridge to further his education and was assigned to HMS Canada. He was a carefree young man with light hair, blue eyes, a slight build and, noted a journalist who met him that year, ‘a very boyish and bashful appearance’. He was one of Victoria’s favourite grandchildren and the Admiralty was ordered to send her daily telegrams so that she could keep track of his voyages.

All she needed to do, however, was read the newspapers. Despite the Fenian threats and fears of possible assassination attempts, little effort was made to keep the prince’s itinerary secret. The press followed his movements in considerable detail. Anyone who opened the next day’s New York Times could confirm his arrival in Halifax on 1 August. His tour of central Canada, including official events in Ottawa and Toronto, received plenty of ink and he was back in Halifax and back aboard HMS Canada by the middle of October.

In New York, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa appears to have been keeping tabs on the prince—and plotting. He was an ‘indefatigable and patriotic dynamiter’ who ‘spends his days and nights in evolving schemes to bring the haughty British lion to its knees by means of explosives’, observed The New York Times. Convicted of treason in Ireland, he had been exiled in 1870 to the US, where he had established the United Irishman to continue the fight for Irish independence. He was convinced that his ‘skirmishers’ could strike the decisive blows that would force Britain to withdraw from his homeland. It’s likely that Rossa personally selected Holmes and Bracken to go to Halifax.

Meanwhile in Halifax …

Above: A drawing of a Fenian ‘infernal machine’ (time bomb). (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 15 March 1884)

After stumbling upon the cache of dynamite, Detective Power rounded up and arrested his suspects. They had expected either to find trouble in Nova Scotia or to create it. Tucked into Holmes’s pockets were a loaded revolver and a four-chamber pistol with its barrel sawn off, a few loose rounds and two dozen blasting caps. Power’s search of Bracken turned up another loaded revolver, spare rounds, more blasting caps and a small key that fitted the lock on one of the dynamite-filled suitcases stashed in their hotel room.

Holmes had another incriminating piece of evidence in his pocket—a baggage claim issued at Halifax’s main terminal. Power hurried to the station and retrieved the checked item. It was a parcel wrapped in canvas, stamped with the words ‘Gregg & Co., New York’. Inside was a Boyton wet suit, named for its Irish-American inventor Paul Boyton; with built-in flotation material and a rubberised outer shell, it was the perfect attire to protect anyone inclined to swim in the chilly waters of Halifax Harbour. A member of an Irish group in New York had recently tested a Boyton in the Hudson River, offering what the New York Times described as ‘a practical illustration of how a man in a swimming suit might blow up a vessel with certainty and safety’.

Police turned their attention to the luggage found at the Parker House Hotel. Both valises contained a small clock in a round case, bearing the logo of the American Clock Company. A mechanism had been added to each clock, and a Halifax watchmaker suspected that it transformed them into the timing device for a bomb. The dynamite, manufactured in the United States by the Atlas Powder Company, was known as ‘triple-charge’, with a high (65%) nitroglycerine content—six times more powerful than ordinary dynamite. It was enough explosive, Washington DC’s National Republican newspaper later reported, to blow heavily fortified George’s Island in Halifax Harbour ‘to pieces’. A half-dozen sticks ‘properly placed against the stern or side of a man-of-war’, the paper added, ‘would tear a hole in her big enough to sink her instantly’.

Above: ‘CAN’T YOU PUT YOUR FOOT DOWN ON THAT BEAST?’—a Punch cartoon attacking the US government’s refusal to rein in O’Donovan Rossa and other Fenian extremists. (14 June 1884)

Lack of direct evidence

The press was convinced that the men were terrorists. For years, O’Donovan Rossa had been toying with the idea of building a miniature submarine to attack British warships. A swimmer wearing a Boyton suit and carrying a powerful time bomb was the next-best thing. ‘Dynamite Plot in Nova Scotia’, blared a headline in the Times of London, while the city’s Standard identified Holmes and Bracken as ‘members of the dynamite conspiracy’. Superintendent Arthur Sherwood of the Dominion Police, Canada’s federal force, fired off a letter urging Power to interrogate the suspects and to find out ‘if they are emissaries of O’Donovan Rossa’. They insisted, however, that they were miners in search of work, and that the explosives were intended to break rock, not sink ships. With no evidence that they had conspired to attack the warship or kill the prince, they could only be prosecuted for the offence of careless storage of explosives and creating ‘great danger and peril’ for ‘the subjects of our Lady the Queen’.

The Royal Navy belatedly beefed up security, surrounding HMS Canada and other warships anchored in Halifax with cordons of small boats and posting rifle-toting sailors on their decks. Within days Prince George’s ship received new orders and sailed for the Caribbean.

Holmes and Bracken stood trial in March 1884 and a jury deliberated for just twenty minutes before finding them guilty. The presiding judge, John Thompson—a future prime minister of Canada—believed that the offence was serious and the amount of dynamite discovered ‘was so great’ that even careful storage ‘would not produce safety’. But the crime was a minor one under Canadian law and he imposed a sentence of just six months at hard labour, in addition to the seven months they had been in jail since the arrests. Their release in the fall of 1884 set off alarm bells within the Admiralty, where officials feared the ‘Halifax Dynamiters’ might try to launch another attack. In a secret memorandum, the British government was asked to circulate their photographs and descriptions and to keep the pair under surveillance. Britain’s foreign secretary, Earl Granville, granted the requests and assured naval officials on 4 November that ‘steps have been taken to watch the movements of Holmes and Bracken’ upon their return to New York City. Their names, however, do not reappear in British records of Fenian activities. A rumour later surfaced that Bracken, after his release, admitted that the discovery of the dynamite had foiled their plot. ‘We came here to destroy any British property we could,’ he reputedly confessed before returning to the US, ‘especially HMS Canada where Prince George was.’

A single act of terror could have poisoned Anglo-American relations and dramatically altered history. The sudden death of George’s older brother, Prince Albert, of ’flu in 1892 put him directly in line for the throne. A detective’s hunch that two visitors might be burglars ensured that he would become King George V in 1910.

Dean Jobb is professor in the Master of Fine Arts in Creative Nonfiction program at the University of King’s College in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

FURTHER READING

J. Gantt, Irish terrorism in the Atlantic community, 1865–1922 (New York, 2010).

S. Kenna, War in the shadows: the Irish-American Fenians who bombed Victorian Britain (Sallins, 2013).

K.R.M. Short, The dynamite war: Irish American bombers in Victorian Britain (Dublin, 1979).

N. Whelehan, The dynamiters: Irish nationalism and political violence in the wider world, 1867–1900 (Cambridge, 2012).