The execution of the ‘Manchester Martyrs’, 1867: Special Constable Samuel Page’s letter to his mother

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, General, Irish Republican Brotherhood / Fenians, Issue 6 (Nov/Dec 2011), Volume 19

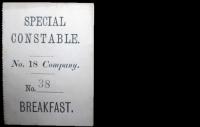

Samuel Page’s signed ‘special constable’ armband.

Samuel Page was sworn in by the Manchester Police Constabulary to act as a ‘special constable’ for the duration of the weekend of the executions and was stationed directly in front of the condemned men at the foot of the gallows. A large number of ‘respectable’ local men were commissioned in such a fashion in order to aid the police and military, as there were widespread fears that armed Feniansor mobs of Irish sympathisers might try to disrupt proceedings. Writing to his mother, Page left a detailed account of his activities over the course of the weekend, beginning ‘now for the particulars of the most awful sight I ever saw in my life’.

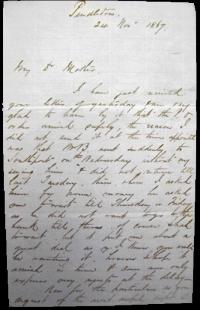

The opening page of Special Constable Samuel Page’s letter to his mother, 24 November 1867.

Page’s account begins the night before the hangings, while he and his men were quartered near the prison. With the atmosphere tense across the city’s many Irish districts and paranoia about Irish revolutionaries rampant in the newspapers, the mayor was in a celebratory mood and treated the officers guarding the gallows to a voluptuous supper. Page writes:

‘for once in their life the corporation treated the officers like gentlemen . . . in all about 25 sat down to an excellent feast, laid out on a table beautifully decorated with the corporation plate and headed by the Mayor himself. The fare consisted of turkey, ham, chickens, ducks, roast and boiled beef, pigeon pie, lobsters, grapes and several kinds of fruits.’

With the executions set for early morning, thousands of extra police, along with the 72nd Highland Regiment, were stationed across the city amidst a nervous atmosphere. Page’s company were detailed to guard the gallows throughout the night to safeguard the venue against sabotage by members of Manchester’s large Irish community:‘We arrived at our destination right in front of the scaffold, much to the disgust of a good many of our men. There we remained the only recipients of the stunt (with the exception of a few would-be spectators at the barricades).’

With the authorities enlisting as many men as they could as special constables to ensure order in the city, Page did not have a very good impression of some of his fellow ‘specials’, noting: ‘I do not know what possessed the Mayor to swear so many such fellows in, they were neither use nor ornament. I was very nearly taking 2 or 3 of them in myself for obstructing our men in discharging their duties.’Page writes with a distinct lack of triumphalism or vindictiveness about the execution scene itself and details the men’s final moments with empathy and compassion:

Meal tickets for the special constables who guarded the gallows. According to Page, for the supper the night before the executions ‘the fare consisted of turkey, ham, chickens, ducks, roast and boiled beef, pigeon pie, lobsters, grapes and several kinds of fruits’.

‘. . . about two minutes after the prison clock struck 8 the door opened and Allen appeared under the arch, whispering some prayers. The rope was put on him and this cap pulled over his eyes when Gould [a.k.a. O’Brien] appeared, he shakes hands with Allen and kissed him, saying very courteously “Good bye Allen”, then kept repeating very quickly “Jesus have mercy on me” which was taken up by Allen.’ According to Page, the condemned duo, O’Brien and Allen, appeared to scorn their comrade Larkin in their final moments, something subsequently omitted from nationalist lore surrounding the executions. Larkin had claimed in his trial that he felt coerced into participating in the raid and this may have undermined him in the eyes of his fellow conspirators. Page writes: ‘Larkin then came in and he was taken no notice of by the other two, as soon as the cap and rope was put over him he fell over in a faint against Gould’. While his two comrades drew comfort from each other, it was left to the hangman, William Calcraft, to come to the assistance of the distraught Larkin; Calcraft ‘took hold of him by his shoulders and placed him on his feet again saying “stand up man, stand up’’’. Of the condemned men’s final moments, Page writes:

The base of the monument to the Manchester Martyrs in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin.

(All images: National Library of Ireland)

‘. . . they did not appear to jerk very hard but rather to slide down. Gould died at once, his rope never stirred. Allen kicked a little but Larkin’s struggles were very serious. Mother it was an awful sight, I could not take my eyes off them. At nine they were cut down and taken inside for burial. I am so glad it is all over for I should not like to see the same sight again.’

This manuscript can be downloaded from the National Library of Ireland’s flickr website, along with all the material featured in this series. HI