The Ethnic Mix in Medieval Wexford

Published in Features, Gaelic Ireland, Issue 1 (Spring 2002), Medieval History (pre-1500), Volume 10

Fig.1—Place-names of Norse provenance in county Wexford. (Matthew Stout)

The Gaelic kingdom of Uí Chennselaig, which was controlled by a dynasty of the same name, is substantially represented by the modern county of Wexford. Some of the ten divisions, or tuath, into which Uí Chennselaig was divided are represented by the baronies of Bantry, Shelburne, Shelmalier, Forth and Bargy. From the tenth century onwards the Norse town of Wexford added an extra cultural dimension to the south of the region. The Norse influence was not confined to the town as the survival of Norse place-names indicate that they controlled the southern coast with an extensive presence in the barony of Forth (fig.1). This is supported by late thirteenth-century documentary evidence for a concentration of Ostmen (Norse) in the vicinity of Rosslare. The survival of Irish place-names of Norse provenance points to a mixed rural population of Hiberno-Norse in the barony of Forth working side-by-side to supply the town of Wexford with essential supplies. The decision by Diarmait Mac Murchada, deposed king of Uí Chennselaig and Leinster, to seek aid from the Angevin king Henry II, led to the conquest of much of Ireland by the Anglo-Normans and the arrival of successive waves of settlers, a movement that can be seen as part of the wider European experience of population expansion during the Middle Ages. The ethnic origins of these settlers reflected the cultural make-up of English society following the conquest of England by the Normans in 1066. The kingdom of Uí Chennselaig was the focus of initial Anglo-Norman activity and settlers were attracted from England and Wales by offers of land and increased social status.

The multi-ethnic nature of society in Anglo-Norman controlled Ireland was sometimes reflected in the dedications of late twelfth and early thirteenth-century charters. For example, in 1175, Raymond le Gros issued a charter to ‘all present and future, French, English, Flemish, Welsh and Irish’, and in 1200, William Marshal’s charter to Tintern Abbey was addressed to ‘all his men, French and English, Welsh and Irish’. Because of their disparate origins, there has been much discussion as to whether ‘Anglo-Norman’ is the most suitable term to describe the migrants who colonised Ireland following military intervention in the 1170s. For the most part, they called themselves ‘English,’ but from the earliest days of the colony experienced what might be called a crisis of identity, as, to quote the phrase attributed by Gerald de Barry to Maurice FitzGerald, ‘they were Irish to the English and English to the Irish’. This analysis of recorded settlers, who came to County Wexford during the first century of the colony, explores the diversity which was so carefully referred to in early charters.

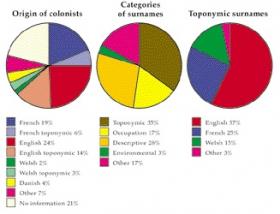

Fig.2—Origins of 455 colonists recorded in County Wexford, 1169-1324. (Matthew Stout)

The Irish on the manors

The native Irish can be divided into two categories: those who continued, where possible, to observe customary life-styles and land-holding practices, and another group, perhaps relatively small in number, who, as betaghs (native Irish living as serfs on a manor), became part of the feudal structure and, as economic assets, were recorded in manorial extents. Occasionally, Irish were fully integrated into the feudal system, receiving charters to hold land in some instances. In County Wexford, for example, Donenald O’Helell held two carucates at Dernach (unidentified) in 1230, on the manor of Duffry and a branch of the Mac Murchada held the manor of Curtun (Courtown) in the early fourteenth century, but the majority of the native Irish are virtually invisible in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century documents. There is some evidence, particularly in the ministers’ accounts for the manor of Ross, to show that the Irish played a significant part in manorial affairs in County Wexford. There was a district known as Balibetagh at Old Ross, but in 1281 it was occupied, not by betaghs, but by Robert the Clerk who paid 66s. 8d. rent for two carucates there. In the same year William O’Dermot and his companions paid 16s. 2d. rent for fifty-four acres in Balidermot (not identified) and Raymond O’Dermot was referred to as ‘one of the betaghs of the earl’, indicating that the betaghs were members of the O’Dermot family group and occupied the district known as Balidermot. An unspecified number of betaghs paid £17 5s. 3d. rent for nineteen carucates spread over eleven locations. A distinction was made between these and ‘certain betagii’ who held their lands by labour dues worth 4s. 2d. and nineteen hens (one each) at Christmas. The betaghs were mentioned a number of times in connection with the work which they did during the harvest: they were paid and fed for this work so it cannot have been part of their customary duties. They appear to have been quite few in number. Part of their fixed custom was to contribute a hen

The deserted town of Clonmines, established by the Anglo-Normans at the head of Bannow Bay—initially successful but deserted by the seventeenth century. (Billy Colfer)

at Christmas and in 1285 only seventeen hens were received, with the comment that ‘if there had been more betaghs, there would have been more hens,’ suggesting that there was room on the manor for more labourers and tenants.

Although documentary evidence relating to the Irish is rare, there are indications that their presence on the manors in the county was pervasive. It is generally considered that, in a manorial context, betaghs held specific townlands which were cultivated in the Irish system. This was the case on the manor of Taghmon where two carucates of uncultivated land and wood were held by the Irish. On the manor of Rosslare the betagii held six carucates at Athard (not identified) and unnamed Irish and English tenants paid £2 rent for two carucates at Ballyregan and Ballysampson. Betaghs were an important element on three of the six episcopal manors in the county, particularly at Mayglass and Polregan where their rents contributed one-third of the manorial income. It is possible that, at least in thinly-settled districts, Irish septs maintained their identity and way of life on the core area of traditional lands. There are some indications that this was the case in County Wexford, particularly in the northern part. In 1324, for example, the hostages of the O’Breens of Duffry were delivered to Wexford castle, an indication that the O’Breens existed as a cohesive group in a particular location.

The origins of settlers

A search of contemporary accounts, charters, manorial extents, inquisitions and justiciary rolls has yielded 455 surnames of individuals who lived within the feudal structure in thirteenth-century Wexford (fig.2). Many of these names recur frequently but have been included only once. These names represent a broad cross-section of society, ranging from the holders of major fiefs to tenants-at-will and tradesmen. Only three women are recorded as land-holders: in 1240, Margery, the wife of Giles, quit-claimed land to Dunbrody Abbey in return for 20m (?); Alina de Heddon held the manor of Magh Árnaidhe (Adamstown) in 1247 and, later in the century, Christinia de Mariscis held the manor of Curtun (Courtown). Another woman is mentioned in a different context: when Roger Bigod paid £35 6s. 8d. to recover lands on the manor of Old Ross from William Severne, Severne’s wife received 40s. to buy a new robe as part of the agreement. The names of principal military tenants, and some free tenants, are well known and, in most cases, have survived to the present time. Some of the names of ordinary settlers are also in current use but most did not survive. It is likely that some of the individuals whose names were recorded, particularly officials of various kinds, spent only a short time in Ireland where they were paid to perform a specific task. Of these names, 360 (79 per cent) are listed in genealogical dictionaries as accepted surnames. By entering these names on to a database, they can be sorted under origin, category, meaning and distribution. Anglo-French names, at 25 per cent (including 6 per cent toponymic names), are in a slender majority over English names, at 24 per cent. English names could be as high as 38 per cent with the inclusion of toponymic names, but it is not possible to say if these persons are of English origin; for example, John of Exeter need not necessarily be of English extraction. Names of Welsh origin, with Welsh toponymic names, make up 5 percent, almost equalled by names of Danish origin at 4 per cent. The surnames can be grouped into five categories: toponymic, occupational, descriptive/nickname, environmental and others. Toponymic names compose 35 per cent of the total and of these 57 per cent are English, 25 per cent French, 15 per cent Welsh and others 3 per cent: descriptive names account for 28 per cent, occupational names for 17 per cent, environmental for 3 per cent and ‘others’ for 17 per cent.

A search of contemporary accounts, charters, manorial extents, inquisitions and justiciary rolls has yielded 455 surnames of individuals who lived within the feudal structure in thirteenth-century Wexford (fig.2). Many of these names recur frequently but have been included only once. These names represent a broad cross-section of society, ranging from the holders of major fiefs to tenants-at-will and tradesmen. Only three women are recorded as land-holders: in 1240, Margery, the wife of Giles, quit-claimed land to Dunbrody Abbey in return for 20m (?); Alina de Heddon held the manor of Magh Árnaidhe (Adamstown) in 1247 and, later in the century, Christinia de Mariscis held the manor of Curtun (Courtown). Another woman is mentioned in a different context: when Roger Bigod paid £35 6s. 8d. to recover lands on the manor of Old Ross from William Severne, Severne’s wife received 40s. to buy a new robe as part of the agreement. The names of principal military tenants, and some free tenants, are well known and, in most cases, have survived to the present time. Some of the names of ordinary settlers are also in current use but most did not survive. It is likely that some of the individuals whose names were recorded, particularly officials of various kinds, spent only a short time in Ireland where they were paid to perform a specific task. Of these names, 360 (79 per cent) are listed in genealogical dictionaries as accepted surnames. By entering these names on to a database, they can be sorted under origin, category, meaning and distribution. Anglo-French names, at 25 per cent (including 6 per cent toponymic names), are in a slender majority over English names, at 24 per cent. English names could be as high as 38 per cent with the inclusion of toponymic names, but it is not possible to say if these persons are of English origin; for example, John of Exeter need not necessarily be of English extraction. Names of Welsh origin, with Welsh toponymic names, make up 5 percent, almost equalled by names of Danish origin at 4 per cent. The surnames can be grouped into five categories: toponymic, occupational, descriptive/nickname, environmental and others. Toponymic names compose 35 per cent of the total and of these 57 per cent are English, 25 per cent French, 15 per cent Welsh and others 3 per cent: descriptive names account for 28 per cent, occupational names for 17 per cent, environmental for 3 per cent and ‘others’ for 17 per cent.

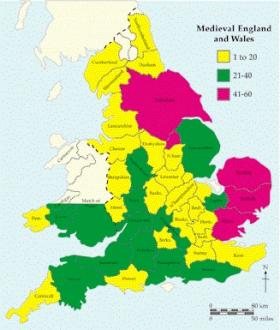

Of recorded names, eighty-one (18 per cent) can be associated with a specific place of origin in England or Wales. (fig.3). For mapping purposes, these are divided into pre- and post-1250. It is relatively easy to find documentary evidence for the origins of high profile families, most of whom arrived in the early days of the conquest and held land by military service. These originated mostly in south Wales, particularly in Pembrokeshire, with single examples from Devon, Sussex, Buckinghamshire and Staffordshire. Place-names in south Wales, and particularly

Many settlers lived in defended farmsteads now referred to as moated sites. Of the 190 examples identified in County Wexford, the majority are located in the central frontier area between Gaelic north and English south. Rochestown moated site (above), probably represents the farmstead of Adam Roche who held two carucates at Trilloc on the manor of Old Ross in 1307. It is likely that Trilloc became Rochestown. (Billy Colfer)

Pembrokeshire, provide additional indications for the origins of these families. For example, Bosherston, Sigingston, Hayscastle and Bonvilston in south Wales are named after families which were represented among the settlers in Wexford. Other Wexford settlers, principally Prendergast, Roche, Barry, Sutton, Carew and Canton were named after their Welsh places of origin. It is significant that the character of place-names in Pembrokeshire have more in common with south Wexford or England than with the rest of Wales.

Evidence of former links with France, particularly Normandy, is provided in twenty-eight topographic surnames, including de Montmorency, de Quency, de Boisrohard, de Valle, Neville, Devereux, Rochford, Tracy, Bataille and Cullen. Descriptive surnames, referring to a physical or personality trait, make up 28 per cent of the total. Examples, both English and French, include: Pettit: small, Browne: brown, Russell: red, Cheevers: goat, Hore: white-haired, Whitty: white-eye, Curtis: courteous, Sinnott: bold in victory, Esmonde: east man, Prat: cunning, Pigeon: easy to pluck, Payne: villager, Bennett: blessed.

Records of the later thirteenth century show that, while south Wales was still well represented, colonists were being attracted from a much wider area, particularly Devon and Somerset, the midlands and Yorkshire. The existence of clusters in Devon, Sussex and the mid-lands may indicate that earlier colonists from these areas attracted others to Ireland at a later stage. There is an obvious difference in the type of name being recorded, as most belonged to the lower categories of society. Names like de Derby, de Stanton, de Warrick and de Isham became more common as people were more frequently identified by associating them with their places of origin. However, this type of name may not have indicated a direct link with a particular place but rather a historic family connection. Names, both French and English, based on trades and occupations make up 12 per cent (fifty-six names) of the total. Names of burgesses, such as le Napper (cloth-maker), le Wympler

Fig.4—Recorded occurrences in England and Wales of surnames found in County Wexford 1169-1324.

(veil-maker), Vitrear (glass-maker), Hoser (hose-maker), le Nedler (needle-maker), le Taillour (tailor), Merser (fabric merchant) and Chapman (merchant/trader) indicate the industrial nature of urban activity. Various trades used as surnames, for example, Slater, Porter, Palmer (pilgrim), Archer, Sherman, Shepherde, Sergeant, Meyers (physician), Dorebar (plasterer/ dauber), le Leche (physician) and Hussier (usher) highlight the wide range of specialist activity required for the effective operation of the colony. Ten people (about 2 per cent) with what appear to be Irish names were mentioned in a manorial or urban context; one of these, Donewth O’Hony, was provost of the manor of Old Ross. The presence of six Italian customs collectors at New Ross, probably doing a tour of duty as ‘consultants’, emphasised the diverse ethnic mix of medieval port towns.

As well as mapping the known places of origin, a distribution map of the recorded occurences in England and Wales of the 355 identified surnames recorded in medieval Wexford can be compiled, as documentary evidence usually associated surnames with a number of English and Welsh counties (fig.4).By calculating all recorded mentions of names, it is possible to create a map showing three levels of evidence for the existence in Britain of the identified Wexford surnames. There is some correlation between this map and the distribution of known origins. The area around the Bristol Channel emerges in the middle of the scale, with the exception of Cornwall and, surprisingly, Pembrokeshire. There is also a continuous band in the middle of the scale stretching from Staffordshire in the west midlands to Hampshire on the south coast. Yorkshire, as in the previous map, and the region of East Anglia, between the Thames estuary and the Wash, emerge with the highest incidence of recorded surnames. Migration from the east coast counties, which had the highest density of moated sites in England, could be associated with the secondary wave of settlement with which the moated sites in Ireland are usually associated. The acquisition by the Bigod earls of Norfolk, at the partition of Leinster in 1247, of the manors of Old Ross and the Island in County Wexford, could explain the high level of migration from the East Anglia area. This map is source dependent, and represents the distribution in England and Wales of families which were represented in County Wexford. However, taken in conjunction with the distribution map of known origins, it does suggest that the sourcing of settlers, initially concentrated in south Wales and the Bristol Channel region, became much more wide-spread but with regional concentrations.

The distribution of settlement features and cultural practices within the county was directly related to the conflict between settler and native Irish. Initial expansion was

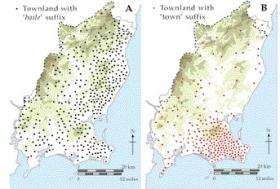

Fig.5—The barony of Forth is the only place in Ireland where there is a concentration of both ‘baile’ and ‘town’ place-names. (Matthew Stout after T. Jones-Hughes)

forced by a Gaelic recovery to contract to a naturally defended ‘pale’ in the south of the county. This led to the emergence of an English south and a Gaelic north, separated by a hybrid frontier area. The contrast between these regions was manifested in a number of ways, including distribution of settlement features, size of holdings, place-names and family names. Place-names provide valuable evidence for settlement: it is suggested that concentrations of baile place-names are an indication of a Gaelic presence throughout the medieval period (fig.5). Conversely, concentrations of townlands containing the element ‘town’ are found in areas which experienced the most durable impact of Anglo-Norman colonisation and settlement. In Wexford, baile names are located in a broad band along the east coast and in the south-east barony of Forth. The poor quality of soils along the east coast may have militated against a significant influx of colonists, allowing the Irish to remain dominant. In the mid-nineteenth century, this region where there is a concentration of baile place-names, was also the most Gaelic in terms of its range of family names. The anomalous, and unique, concentration of both ‘town’ and baile place-names in the barony of Forth, combined with the presence of Ostman descendants of the Wexford Norse, supports the documentary evidence for the presence of a multi-ethnic community in medieval times. The legacy of this diversity was of enduring significance: in the mid-seventeenth century, the highest concentration of Old English personal names in Ireland was to be found in Forth and Bargy and in this district, isolated by topographical features and described as the ‘Wexford Pale’, a unique dialect known as Yola survived until the mid-nineteenth century. In contrast, Gaelic family names, for example, Kavanagh, Kinsella, Doran, Bolger, Kehoe and Murphy are associated mostly with the north of the county.

Recorded names represent only a small fraction of those who migrated from Britain to Ireland and of these only about 16 per cent can be associated with a place of origin. The variety of names does vindicate the addressing of early charters to a multi-ethnic society. However, there is one very noticeable exception: members of the Flemish

colony in Pembrokeshire, regarded as an integral part of the initial settlement in Ireland, are almost invisible in the Wexford record. Indeed surnames usually regarded as Flemish, including Cheevers, Sinnott, Whitty, Siggins and Busher, would seem to be of English origin. Perhaps the most obvious factor to emerge from a study of thirteenth-century settlers’ names in County Wexford is the extent to which names introduced at that time (including Roche, Browne, FitzHenry, Neville, Furlong, Rossiter, Lamport, Barry, Sutton, Hore, Butler, Whitty, Stafford, Codd, Devereux, Meyler) continue to be strongly represented in the profile of surnames in the county.

colony in Pembrokeshire, regarded as an integral part of the initial settlement in Ireland, are almost invisible in the Wexford record. Indeed surnames usually regarded as Flemish, including Cheevers, Sinnott, Whitty, Siggins and Busher, would seem to be of English origin. Perhaps the most obvious factor to emerge from a study of thirteenth-century settlers’ names in County Wexford is the extent to which names introduced at that time (including Roche, Browne, FitzHenry, Neville, Furlong, Rossiter, Lamport, Barry, Sutton, Hore, Butler, Whitty, Stafford, Codd, Devereux, Meyler) continue to be strongly represented in the profile of surnames in the county.

Billy Colfer is a former school teacher.

Further reading:

B. Colfer, Arrogant Trespass: Anglo-Norman Wexford 1169-1400 (Enniscorthy 2002).

P.H. Hore, History of the Town and County of Wexford, 6 vols. (London 1900-11).

M. Moore, Archaeological Inventory of County Wexford (Dublin 1996).

E. St. John Brooks (ed.), Knights’ Fees in Counties Wexford, Carlow and Kilkenny (Dublin 1950).