THE CURIOUS CASE OF REVD JAMES GODFREY MACMANAWAY MBE, CLERGYMAN, SOLDIER AND POLITICIAN

Published in Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2022), Volume 30By Aaron Callan

Revd James Godfrey MacManaway—or ‘JG’, as he was often known—was born in 1898, the son of the Rt Revd Dr James MacManaway, bishop of Clogher. He was educated at Campbell College and then Trinity College, Dublin. At the age of sixteen, whilst at Campbell College, he enlisted and fought at the Battle of Loos before joining the Royal Flying Corps. In 1923 he was ordained as a minister in the Church of Ireland by the archbishop of Armagh and would serve a curacy at Drumachose, Limavady, before taking up the position of senior curate at Christ Church, Londonderry. In 1930 he became the rector and would stay there for seventeen years. In 1926 he married Catherine Anne Trench MBE.

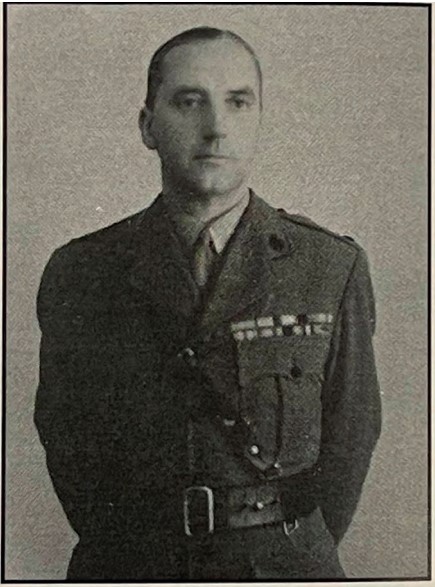

MacManaway again served during the Second World War as a senior chaplain. He took part in the evacuation of Dunkirk with the 12th Royal Lancers and would later see action in the Middle East as senior chaplain to the First Armoured Division. In February 1945 he was posted to the Italian front as senior chaplain to the 10th Armoured Division. For his services he was awarded the MBE.

POLITICS

In 1947 MacManaway turned his attention to politics; he was elected Unionist member for the City of Londonderry in the Northern Ireland parliament, winning a majority of 4,028 over a Labour opponent, and he held the seat in 1949 against a Nationalist, on both occasions taking over 60% of the vote. MacManaway was regarded as very gifted and as one of the most colourful personalities in the Church of Ireland. Contemporaries would speak of his gift for storytelling and that he could hold an audience spellbound. As a result, sometimes he let his imagination get the better of him, often to amusing effect. One such story he told was about his escape from Dunkirk. As they were sailing for England, his boat was hit. ‘I was swimming around for two hours before I was picked up!’, he told an admiring audience. The bubble was soon burst when his wife in a clear voice announced, ‘But Godfrey, you know you cannot swim’.

His ambitions were soon set on attaining a seat in Westminster, although, as a man of the cloth, there was some doubt as to his eligibility, as historical statutes debarred clergymen of both the Established Church and the Roman Catholic Church from sitting as MPs in the House of Commons. MacManaway would seek out legal advice, which he got from the attorney general of Northern Ireland, Edmund Warnock. Warnock advised MacManaway that since the Church of Ireland had been disestablished in 1869 the statutory bars did not apply to him.

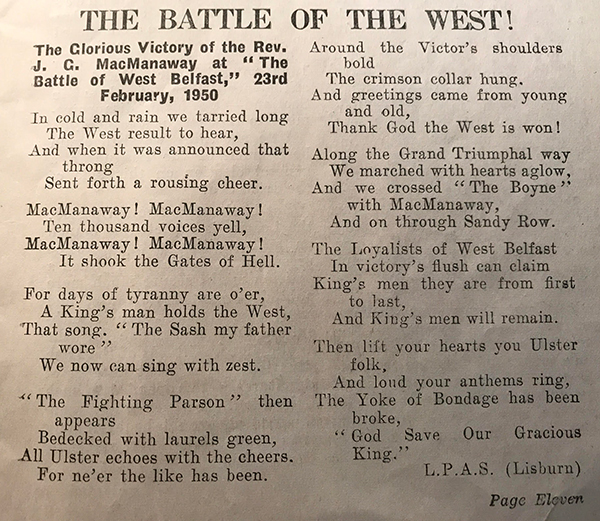

Above: ‘THE BATTLE OF THE WEST’, celebrating MacManaway’s victory in West Belfast in the 1950 general election. (The Unionist Voice)

On the back of this advice, MacManaway put his name forward for the West Belfast constituency and was selected by the Unionist Party to contest the seat in the 1950 general election. As a precaution, he resigned his offices in the Church of Ireland and relinquished his rights as a priest in the Church. After a vigorous campaign, he won the seat for the Unionists by defeating the sitting MP, Jack Beattie (Labour), by an impressive majority of 3,378. Among the many activists who helped out in the campaign was a young Ian Paisley.

ELIGIBILITY AS MP QUESTIONED

Above: Revd James Godfrey MacManaway in senior chaplain’s uniform during the Second World War.

MacManaway was the first clergyman to take a seat in the House of Commons in 150 years and this would cause a stir in Westminster. Most likely no one took notice of his candidacy, as he was fighting for a tough seat against a sitting MP. Virtually everyone at Westminster was taken aback when his position as an MP was called into question by a single back-bench Labour MP, Major Geoffrey Bing. Whenever the topic of MacManaway’s membership was raised in the House it caused great debate among members, with a number of Unionist MPs, including Winston Churchill, speaking in his defence. MacManaway was put under the scrutiny of a select committee of the House. They could not or would not reach a decision, however, and with some disquiet they recommended that urgent legislation was required to clarify the law. The matter was then referred to the judicial committee of the privy council by the lord president of the council, Herbert Morrison.

Its judgement identified a lacuna in the existing legislation, which disqualified MacManaway. While the Irish Church Act of 1869 did disestablish the Church of Ireland, there was no express provision in the Act permitting its clergymen to sit as MPs. Therefore MacManaway was subject to the earlier House of Commons (Clergy Disqualification) Act 1801, which debarred any person ‘ordained to the office of priest or deacon’ from sitting or voting in the House of Commons. The privy council decided that the 1801 Act disqualified not only persons ordained in the Church of England but also all persons ordained by a bishop in accordance with either the order of the Church of England or other forms of episcopal ordination. In the case of Revd James G. MacManaway, that included ordination in the Church of Ireland. Thus, in broad terms, any clergy ordained by a bishop were subject to the disqualification, whereas clergy and ministers of religion not ordained by a bishop were not subject to the disqualification: this meant that Revd Martin Smyth, Revd Robert Bradford and Revd Ian Paisley in the future could take their seats in the House of Commons.

DISQUALIFIED

The judgement also ignored later legislation that removed the bar on an ordained priest if he resigned his benefice, emoluments and pension. The Commons would back the judgement and resolved on 19 October 1950 that MacManaway was disqualified from sitting, although it cleared MacManaway of any liability for fines that he had incurred for voting in parliamentary divisions while ineligible. (MacManaway had done so on five occasions.) He was deeply hurt by the judgement, and he bitterly protested a decision taken on the grounds of what he perceived to be an unjust anachronism, which brought his political career to an abrupt end. MacManaway’s career in the House of Commons lasted all of 238 days.

He did not, however, contest the ensuing by-election, and 23-year-old Limavady urban council chairman Thomas Teevan was selected by the Unionist Party. After his selection he said: ‘As the Loyalist candidate I shall call on the entire Loyalist community to rally round me as they rallied round Mr MacManaway’. For his part, MacManaway gave his full support to Teevan. Speaking at a Unionist meeting in Limavady, he said that he was extremely glad that the person chosen to take up the torch which he had not been allowed to continue to hold was ‘another Limavady man, Mr Teevan’. (Teevan won the seat but lost it at the subsequent general election in 1951.)

Above: Thomas Teevan speaking at the opening of Largy Orange Hall, just outside Limavady, in 1953. In November 1950 Teevan won the West Belfast by-election caused by MacManaway’s disqualification but lost in the subsequent general election of 1951.

The local newspaper reported that, in MacManaway’s view, the tide had gone against him owing to a very dirty trick, but he was an old soldier and, like every old soldier, he knew what it was to have to meet disaster as well as triumph: ‘The Socialist Government [Labour was in power at the time] may imagine they got rid of Godfrey MacManaway, but if God spares me they will see Godfrey MacManaway back once more’. He was not able to keep that pledge. He also had to resign his Stormont seat in light of the judgement passed at the House of Commons, which would apply to the Northern Ireland parliament as well.

PERSONAL TRAGEDY AND DEATH

Tragedy would strike MacManaway shortly after leaving the Commons when his wife died in January 1951. His own health, which was never robust, started to deteriorate after her passing. His eyesight began to fail so rapidly that he had practically lost the sight of one eye and was threatened with loss in the other. He could only walk with extreme difficulty, and with the aid of a stick as a support and guide. He was severely injured in a heavy fall when he tripped on the staircase while leaving the Ulster Club in Belfast on his way to address a meeting in support of his successor as MP for West Belfast, Thomas Teevan. ‘MacManaway died a few days later in the Royal Victoria Hospital, aged 53. A verdict of accidental death was returned by the Belfast city coroner, Dr Lowe, who concluded that death was due to meningitis contracted following a fracture of the skull caused by the fall. Lowe also stated that ‘MacManaway would be greatly missed, and he was a gifted man, and scarcely knew when to stop when he was doing something for a cause … One of the causes in which he was interested was the cause of Ulster.’

REMOVAL OF CLERGY DISQUALIFICATION ACT (2001)

Above: Greystone Hall, the Limavady residence of Revd J.G. MacManaway

In the aftermath of the MacManaway case, another House of Commons select committee in 1951 examined the possibility of a change in the law. Although the committee acknowledged the anomalous and anachronistic nature of the ancient legislation, and having considered the views of a number of Christian denominations, it recommended no specific changes to the law. The matter would be untouched for another 50 years until David Cairns, a former Roman Catholic priest, was selected to fight a safe Labour seat, and a potential rerun of the MacManaway case loomed. The Labour government moved quickly and in 2001 the Removal of Clergy Disqualification Act lifted almost all restrictions on clergy, of whatever denomination, from sitting in the House of Commons. Unfortunately for MacManaway, in his own time he was not given that opportunity by a previous Labour government.

Aaron Callan is secretary of the Roe Valley Historical Society and a Limavady local councillor.

Further reading

J.F. Harbinson, The Ulster Unionist Party 1882–1973: its development and organization (Belfast, 1974).

H. Patterson & E. Kaufmann, Unionism and Orangeism in Northern Ireland since 1945: the decline of the loyal family (Manchester, 2007).

B. Walker (ed.), Parliamentary elections results in Ireland 1918–92: Irish elections to parliamentary assemblies at Westminster, Belfast, Dublin and Strasbourg (Dublin, 1992).

G. Walker, A history of the Ulster Unionist Party (Manchester, 2004).