The coin that never was

Published in Features, Issue 2 (March/April 2021), Volume 29The 1972 Northern Ireland twopence piece

By Mark Stocker

“The timing of the coin, closely coinciding with the onset of the Troubles, was unfortunate for its proponents …”

Decimalisation of the United Kingdom coinage was so successful that it was dubbed ‘the non-event of 1971’, and the coins themselves were seamlessly circulated and accepted. Northern Ireland’s experience, however, was altogether unhappier. The story of its proposed but unexecuted twopence coin—which never got off the drawing-board—has not till now been told, although it is comprehensively documented in the Royal Mint files at the National Archives, Kew. It combines metropolitan neglect, local pigheadedness, disappointing designs and broken promises. The timing of the coin, closely coinciding with the onset of the Troubles, was unfortunate for its proponents, while the British government’s subsequent silent inaction aimed to avoid inflaming potential sectarian tensions unnecessarily.

Metropolitan neglect

The first mention in the minutes (1962–7) of the extensive Royal Mint Advisory Committee (RMAC) deliberations on the prospective coinage designs was in 1966. Niall MacDermot, financial secretary to the Treasury, lambasted Christopher Ironside’s proposed reverses for (amongst other shortcomings) including no Northern Ireland designs. When the Mint’s deputy master, Sir Jack James, ‘not very seriously’ proposed the Red Hand of Ulster as an option, MacDermot—the scion of Irish titular princes—replied ‘Over my dead body!’ There matters stood until February 1968, just before the new coins were announced. Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, the long-time RMAC president, astutely, if belatedly, critiqued James’s explanation that the lion of the crest of England on the tenpence could be considered part of the crest of the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland as ‘a little stretched and … unlikely to go down very well in Ulster’.

Deputy Master of the Royal Mint Sir Jack James (left) with coin designer Christopher Ironside (right), c. 1968. (Alamy)

This was an understatement. Ironside’s designs were politely received, although Britannia’s absence overwhelmingly preoccupied British newspapers. This was promptly rectified several months later with her reappearance on the all-new heptagonal 50-pence coin, but only the Daily Mail gave prominence to ‘forgotten’ Northern Ireland. Criticism was inevitably more strident locally. The Belfast Telegraph rebuked Roy Jenkins, chancellor of the Exchequer: ‘We have seen the English lion (10 np) [new pence], Scottish thistle (5 np) and Welsh crest (2 np), but no sign of Ulster’s red hand, or even harp, or shamrock … Remember, Mr Jenkins, it’s our money too.’ The newspaper quoted a Mint spokesman who explained: ‘There has never been a specific Northern Ireland design, although we have shown the shamrock at various times’. An unnamed Unionist MP responded, ‘That is no answer’.

Days later, Robin Chichester-Clark, MP for Londonderry, informed Jenkins of ‘a flood of representations … which reflected the disappointment that there was no Northern Ireland symbol’. Jenkins ‘sincerely sympathised’ with his problem, ‘which is also mine’, and promised action. Robin North, a senior Home Office official with Northern Ireland responsibilities, told the Mint’s David Biggs that the ‘considerable prominence’ given to the ‘territorial significance of England, Scotland and Wales’ on the other coins was unjust, and sought amends with a representative symbol. Biggs replied: ‘One of the main problems is, of course, what symbol could have been used, that is not either common to the whole of Ireland, or provocative’. Deputy Master James rightly predicted that Ulster would ‘in its way be tricky’; what he called the ‘bleats from Northern Ireland’ were getting to him.

The dead hand of the Red Hand

Above: Prime Minister of Northern Ireland Terence O’Neill in 1965. By the mid-nineteenth century the Red Hand had an association with his family, who had assumed the surname ‘O’Neill’ by royal licence in lieu of their original name, Chichester. (Irish Times/Joe Clarke)

With James’s approval, Prince Philip explored options with Northern Ireland’s prime minister, Captain Terence O’Neill. These were limited. While the Red Hand was rooted in Gaelic culture, used heraldically in a mid-fourteenth-century seal, and still survives in Gaelic Athletic Association motifs (most notably for Tyrone), by the mid-nineteenth century it had an association with the prime minister’s own family, who had assumed the surname ‘O’Neill’ by royal licence in lieu of their original name, Chichester. How could he betray his heritage and reject the Red Hand? Somewhat disingenuously, O’Neill assured Prince Philip that this ancient symbol was used in the South to signify one of the four provinces and that ‘its incorporation into a design would certainly not offend anyone across the border’. This, however, was contradicted by James’s information about the emblem’s unpopularity south of the border.

Although Ironside was then preparing several possible designs for the 50 pence, including one featuring a Northern Ireland flax plant, the decision to opt for Britannia rendered the situation more critical. Prince Philip therefore proposed an alternative twopence design to complement the equivalent Prince of Wales Feathers coin which would be circulating on the mainland. This followed the successful precedent of simultaneously circulating English and Scottish shillings. James raised the matter with the Decimal Currency Board (DCB), proposing delayed issue of the Northern Ireland coin. Lord Fiske, the DCB chairman, believed that this complicated a new currency which ‘is being introduced as a means of simplification’, provocatively adding: ‘I cannot believe you did not consider this when the original designs were chosen’. Yet he was in no position to stop the coin. After consulting the Northern Ireland government, Jenkins announced the future twopence in December 1968. Its issue would be ‘confined as far as possible’ to Northern Ireland and would not occur until at least a year after ‘D-day’, 15 February 1971.

By mid-1970 the Mint was considering several design themes, though all posed formal or political problems, and sometimes both. Besides the Red Hand, the shield of the Northern Ireland government was proposed. Should either of them be crowned? Not doing so might bring loyalist objections, and potentially compromised the queen herself, while the crown risked provoking a nationalist political outcry. A further problem with the crowned shield was its visual unsuitability for a relatively small coin. The harp quarter on the royal arms seemed an obvious choice, but it was associated with Ireland as a whole and featured on all the Republic’s coin obverses. Meanwhile, the Northern Ireland government continued to demand the Red Hand ‘either on its own, or in combination with the star, crown and shield which were associated with it’ on the province’s coat of arms.

A designer’s nightmare

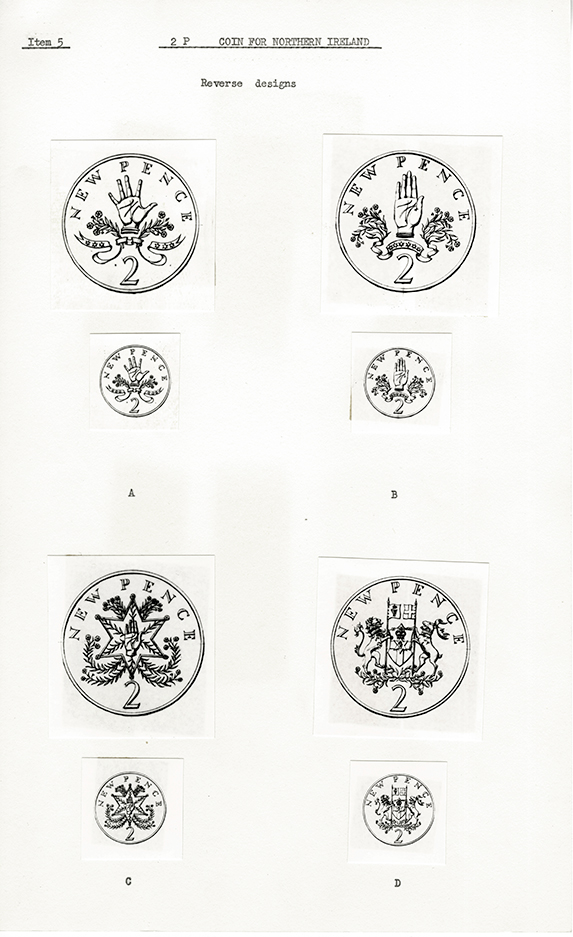

When Ironside was informed of this, his reaction reflected exasperation with the escalating political crisis and sectarian intransigence. He humorously proposed two rival designs, struck ‘for use on opposite sides of the barricades’, inscribed ‘(1) “Bogside über Alles” (2) “Apprentices arise, you have nothing to lose but your oranges”’. Suspending disbelief, he produced four designs for the RMAC meeting in November 1970. Three were variants of the Red Hand, one which looks today like a high-five gesture (A), another with the fingers closed (B) and the third within a six-pointed star, as used on Northern Ireland stamps (C). Each design was ornamented with flax and uncrowned. Design D depicted the Northern Ireland government arms. Ironside believed that A best matched the companion twopence coin, B was ‘forbidding’ and C was distinctively different from the approved Welsh and Scottish designs. While D was, so he thought, ‘symbolically non-controversial’, its basic shape occurred ‘on very many coins all over the world’. When officials previewed the designs, however, they expressed concern that the arms were of the government of Northern Ireland rather than of Northern Ireland itself. As the nationalist minority was largely hostile to the government, D could pose problems: contrary to Ironside’s assumption, it too was potentially controversial. B was preferred to A, as its closed fingers resembled the traditional heraldic symbol more closely. Indeed, Sir Harold Black, secretary to the Northern Ireland cabinet, advised that the ‘spread hand’ should ‘certainly not’ be adopted.

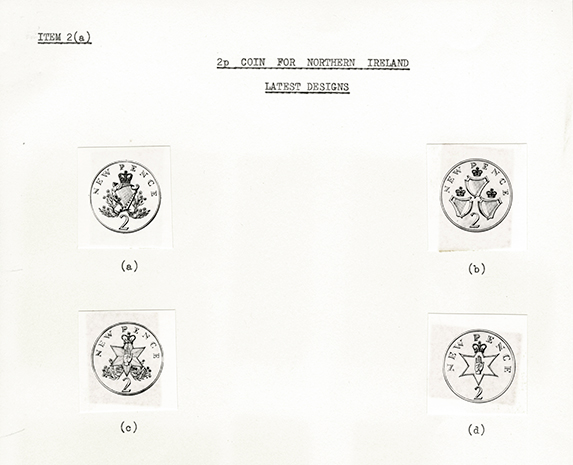

The RMAC was cautious about recommending any of Ironside’s designs, although they were potentially ‘coinable’. The government arms were considered unsuitable for the coin size, while a single crowned harp with the numeral 2 immediately below it was believed difficult to realise successfully. Ironside was therefore asked to produce a design with two or more harps, each crowned, as well as the Red Hand on a star like design C, but with the flax replaced by a crown. He presented four drawings at the next meeting, in June 1971, the first two featuring harps and the other two with the Red Hand. Unfortunately, the Northern Ireland government’s position had recently hardened, with Black declaring that ‘any design including the harp would be unacceptable’. The Red Hand was still preferred; on this basis the RMAC suggested that Ironside further develop his revised design (c), with the hand on a star surmounted by a crown, as (d) obviously looked too stark. Since the committee found the designs ‘undistinguished’, another possibility was a return to the previously rejected government coat of arms. Pared down to the shield and with the supporters omitted, objectionable political content might be diluted; this, however, merely represented a reversion to the suggestion of a year earlier. Ironside went on to produce two further designs by late July, damningly described by RMAC member Robin Porteous as ‘melodramatic, even desperate’, ‘a hotchpotch’, ‘irredeemably provincial’ and ‘rather mingy’. Porteous then analysed the function of the coin:

‘It is not, presumably, the Northern Ireland government as such which we are trying to compliment by this coin, but the whole concept of the Irish under the Crown … the same concept … as is symbolised by the retention of the harp in the Royal Arms and St Patrick’s crown in the union flag. If we cannot find some device which they are all happy with, it will be better not to produce this coin at all.’

Above: Ironside’s designs submitted to the Royal Mint Advisory Committee in November 1970 (top) and June 1971 (below). (UK National Archives, Royal Mint)

In August 1971, Harold Glover, James’s successor, forwarded four designs to Philip Woodfield at the Home Office. Glover told him that the RMAC found them acceptable but undistinguished, and he hoped that the Northern Ireland government could be ‘persuaded to abandon the idea of featuring the Red Hand’. It was up to Woodfield to consider ‘the political consequences of choosing a design … representative of a particular faction rather than all the people of Northern Ireland’. Glover bleakly concluded: ‘In all the circumstances I hope it may be decided to abandon the intention of issuing the coin at the present time’. As the Mint’s raison d’être was to produce and promote new coins, such a statement was unprecedented.

A coin quietly shelved

Above: Belated closure would be given to the numismatically disenfranchised Northern Ireland in 1986 with this £1 coin designed by Leslie Durbin and depicting flowering flax.

On 31 December 1971 the home secretary, Reginald Maudling, outlined the coin’s chequered history to Anthony Barber, chancellor of the Exchequer. He reported the Northern Ireland government’s intransigence over the Red Hand and observed: ‘This has acquired political connotations over the past two years and in some areas has displaced the Union Jack as a symbol of Protestant ascendancy’. The formation in 1970 of the Red Hand Commando, a secretive loyalist paramilitary group that murdered its first victim weeks after Maudling’s letter, tragically confirmed this. He therefore concluded that it would be unwise to continue, and would accordingly inform Brian Faulkner, the Northern Ireland prime minister, though ‘we do not propose to volunteer any announcement for the time being’. Barber concurred and the proposal was quietly shelved in January 1972.

No recorded public mention of the coin occurred for almost another year, when letters from Robin Chichester-Clark and another MP, Guy Barnett, were forwarded to the Mint. In the interim (March 1972), the Northern Ireland parliament was suspended and would be abolished in 1973. In a memorandum to John Nott, minister of state to the Treasury, Alan Dowling of the Mint supplied a brief history repeating Maudling’s points, and added that both the prime minister and the minister for defence concurred. There the matter rested until February 1976, when the Unionist MP Robert Bradford asked when the promised coin with a ‘Northern Irish design’ would be minted. Denzil Davies, a junior Treasury minister, simply replied: ‘I have no present intention in so doing’, given the political situation.

Several months later, Ian Paisley forwarded an aggrieved letter about the coin from a constituent, Thomas Norrell, to the Northern Ireland minister, Roy Mason. Norrell feared that Mason’s office ‘are out to suppress not only Northern Ireland but indeed the democratic majority’, and complained of ‘the inconvenience caused by money from the Republic’. The response drafted for Mason reads tactfully:

‘You and Mr Norrell may rest assured that my attitude on this issue does not indicate any lack of commitment to Northern Ireland as part of the United Kingdom—quite the contrary. I look forward to a peaceful and prosperous future for the Province … I fully appreciate the importance that is attached to emblems and symbols in Northern Ireland. Because of this I would not wish to risk offending any section of the community by changing the status quo. To retain stamps with an Ulster design while not issuing new Northern Ireland coins is entirely consistent with this policy.’

No further recorded comment came from Paisley, who chose his battles carefully: the twopence coin was not one of them.

Two further observations need to be made about the decimal coin that never was. Firstly, though he showed professionalism in delivering the goods, Ironside’s heart never appeared to be in any of the designs. Secondly, political objections aside, the Red Hand symbol is neither aesthetically attractive nor potentially compatible with any other decimal coin design: metaphors of sore thumbs surely occurred to Ironside. Belated closure would be given to the numismatically disenfranchised Northern Ireland in 1986, when the first £1 coins representing the province were circulated. Their design, by silversmith Leslie Durbin, depicts the uncontroversial flax, flowering in all its glory.

Mark Stocker is an art historian based in New Zealand. His book When Britain went decimal: the coinage of 1971 will be published by the Royal Mint / Spink & Sons later this year.

FURTHER READING:

B. Hazard, ‘At Ó Néill’s right hand: Flaithrí Ó Maolchonaire and the Red Hand of Ulster’, History Ireland 18 (1) (2010).

N. Moore, The decimalisation of Britain’s currency (London, 1973).

M. Stocker, ‘The power of ten’, Country Life, 7 October 2020.