The burning of Cork, December 1920: the fire service response

Published in Features, Issue 6 (November/December 2015), Revolutionary Period 1912-23, Volume 23THE SINGLE GREATEST ACT OF VANDALISM OF THE IRISH WAR OF INDEPENDENCE

By Pat Poland

On 21 January 1919 the first Dáil was convened in the Mansion House in Dublin and the independence of the Irish Republic was declared; later the same day, the opening shots in, avant la lettre, the Irish War of Independence were fired on a quiet country road in County Tipperary. Afterwards, in the long period of turmoil from late 1920 to the spring of 1923, Cork City would be buffeted by acts of shocking violence, not least among them the burning of the main shopping district by Crown forces in December 1920.

Arson capital of Europe?

If quirky monikers were being handed out, the city during that unhappy period would undoubtedly have qualified as the ‘arson capital of Europe’. Early in April 1920 Michael Collins ordered the launch of a concentrated series of arson attacks on hundreds of abandoned police barracks with a view to preventing them from being reoccupied. Simultaneously, over 100 Inland Revenue offices were targeted, including those on South Mall and South Terrace in Cork. Even as the city-centre fires raged, a further thirteen RIC stations in the suburbs and county were destroyed. Throughout July, several more were burned down, the fire brigade being prevented by armed young men from getting to work, or, on occasion, being stopped by force of arms from leaving the three city fire stations. The IRA’s objective was to make it impossible, ultimately, for the British administration to function in Ireland.

Fire chief Capt. Alfred J. Hutson (back row, left) and members of Cork Fire Brigade c. 1920.

During October notices began appearing in the press and on flyers around the city, purporting to be from a shadowy body styling itself the ‘Anti-Sinn Féin Society’. Similar notices were signed ‘Black and Tans’ and ‘Secretary of Death or Victory League’. All warned of dire consequences if attacks on Crown forces and members of the loyalist community did not cease forthwith. Their appearance heralded a serious escalation in the workload of Cork Fire Brigade, headed up by the ageing fire chief, Englishman Captain Alfred J. Hutson. Beginning with the attempted burning of the City Hall on 9 October, during the following weeks the brigade would be tasked with over twenty serious incidents, all related to the ‘Troubles’ and many involving the destruction of premises used by Sinn Féin for cultural activities. Throughout that year the city lurched from crisis to crisis in a crescendo of violence. Cork was seized by a kind of madness, the fear that gripped the city infecting all walks of life. During that dark period, the killing of policemen and members of the Crown forces was invariably followed by members of the national movement being targeted and shot. The Volunteers were engaged in activities to maximise Irish freedom, while the British were trying to suppress violence so that it led no further than 26-county Home Rule. In the process, they resorted to copious counter-violence, failing to recognise that overwhelming fire-power could not bring peace unless accompanied by legitimacy.

Sparked off by Dillon’s Cross ambush

On 28 November 1920 at Kilmichael, Co. Cork, seventeen members of the Auxiliary Division RIC (ADRIC) were killed and one seriously wounded by an IRA flying column under OC Tom Barry. Three Volunteers also died in the encounter. Less than two weeks later, on 11 December, their city counterparts launched an ambush on an ADRIC patrol at Dillon’s Cross in Cork’s northern suburbs, just a few hundred metres from the main garrison at Victoria (now Collins) Barracks. One auxiliary policeman died and eleven were wounded.

The Irish War of Independence caused many Volunteers to assert an impassioned patriotism that sometimes manifested itself in over-confidence bordering on recklessness. It proved that, by and large, sporadic guerrilla activity against forces as ruthless as the RIC Special Reserve (‘Black and Tans’) and the ADRIC achieved only a limited military impact, sometimes at high cost to the general, non-belligerent population.

Ever since the Kilmichael ambush a palpable air of trepidation had hung over the city. Now, following the Dillon’s Cross ambush, the fire brigade was alerted to a number of houses blazing nearby, torched as an official reprisal ‘for failure to give warning of an ambush against the police’. Fire Headquarters transferred the call to the Grattan Street station, which responded under Senior Fireman Timothy Ring. The route they travelled took them through St Patrick’s Street in the city centre, and as they turned into the thoroughfare pandemonium reigned. Alexander Grant and Co., a major up-market department store, which stretched from St Patrick’s Street back to Grand Parade, was blazing, the fire being fuelled by drunken ADRIC members, bristling with ordnance and intent on creating havoc. In view of the seriousness of the fire, with its potential to flare into a conflagration, Ring decided to go at once to the Central Fire Station to apprise Hutson of the situation.

![The only known photograph of the burning of Cork, taken during the night of 11/12 December 1920. For those watching from the suburbs, outside the curfew zone, the whole skyline was a shifting orange glow. (The American Commission on Conditions in Ireland: Interim Report [1921])](https://www.historyireland.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Cork-on-fire-300x213.jpg)

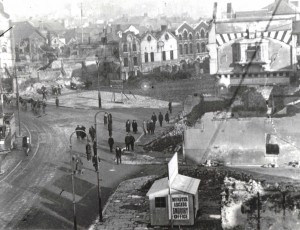

The only known photograph of the burning of Cork, taken during the night of 11/12 December 1920. For those watching from the suburbs, outside the curfew zone, the whole skyline was a shifting orange glow. (The American Commission on Conditions in Ireland: Interim Report [1921])

As the men quickly prepared the horses and equipment, the ever-methodical Hutson had a number of tasks to perform. First, he rang the military at Victoria Barracks and requested them, in view of the enormity of the task facing him in the city centre, to take their fire-fighting appliances to Dillon’s Cross. He later deposed that ‘… they took no notice of my request’. Then he rang the duty engineer at Cork waterworks to ascertain the situation there. Had there been any interference from the auxiliary police or any other quarter? He breathed a sigh of relief when the answer was in the negative. Finally, he looked at his watch. Low tide, he recalled, was at 22 minutes past midnight. Faced with an ebbing tide, he could not depend on the steam fire engine to pump water from the river, but, if required, would have it in place to take full advantage of high water at 6.25 in the morning. It was the period of the new moon, when the tides have the greatest range and strength, and the spring tides would mean that the low tides were very low and the high tides were very high.

Hutson knew that the combined capacity of the two city water reservoirs was some four million gallons, supplied by pumping plant including three triple extension engines and a set of water-powered turbines. The ordinary requirements of the population, including industry, were up to four million gallons a day, however, which would mean, in the normal course of events, that if the reservoirs were not replenished both tanks would be empty in just 24 hours. When the great amount of water required for the fire-fighting task was factored in, the fire chief could face the ultimate doomsday scenario of having a city on fire with no water available in the mains to fight it (to say nothing of the havoc that the lack of water would have wreaked amongst the general population). This is why it was important for Hutson to know that it (probably) had not occurred to the ADRIC to disable the pumping station; if it had, the consequences would not bear thinking about. The failure to exploit this weak link in the city’s fire defences gave Cork at least a fighting chance.

As the small but intrepid unit, led by their silver-helmeted (and silver-haired!) principal officer, set out on that ‘calm, cool night’ to take on the biggest conflagration in Cork in 300 years, they galloped into a city centre teeming with volatile, drunken veterans of the Western Front armed to the teeth with revolvers, rifles, bayonets, bombs and jerrycans brimming with petrol. For all the firemen knew, a fusillade of bullets might greet them upon arriving in St Patrick’s Street. Pusillanimity, however, did not form any part of their agenda.

Cork (left) and Dublin fire-engines pumping water from the River Lee at Merchant’s Quay. (NLI)

The morning after—Cork citizens pick their way through the rubble.

Triage’

Fire-fighters are used to taking control at an incident, containing the damage, minimising injuries as far as possible, and setting its boundaries. This one, however, was on a scale outside of their collective experience. Multiplying and mutating rapidly, it was unlike anything any of them, including their London-trained and experienced chief, had ever encountered. The brigade was now dealing with the dreaded conflagration, a fire involving a number of buildings. For such a task it was singularly under-equipped, and Hutson had to make the unpalatable decision to ‘triage’: many premises would simply have to be allowed to burn while he did his best to contain the fires within a specified area. As the enormous fires sucked in more and more oxygen to feed their insatiable demands, the paintwork on the opposite side of the wide St Patrick’s Street began to blister. Upon seeing this, the fire chief must have been at his most apprehensive throughout that long night. By 11pm most of the south side of St Patrick’s Street was on fire. The columns of flame now moved further southwards, their unstoppable force feeding greedily on the buildings in Morgan Street, Robert Street, Oliver Plunkett Street (north side), Cook Street, Winthrop Street, Winthrop Lane, Caroline Street, Maylor Street and Merchant’s Street. Twenty of the principal establishments with a footprint on St Patrick’s Street were involved, as well as a further 30 businesses on the side-streets. The total area now on fire was some five acres—an area about the size of three football pitches. For those watching from the suburbs, outside the curfew zone, the whole skyline was a shifting orange glow. Elsewhere across the city, on Grand Parade, Oliver Plunkett Street, Washington Street and Bridge Street, business premises were looted and sacked by the ADRIC and ‘Black and Tans’. The City Hall, municipal offices and nearby Carnegie Free Library were bombed and set on fire, the party of firemen sent to guard them being shot at and Mills bombs lobbed in their direction.

By Sunday afternoon (12 December) the Cork fire-fighters were all but worn out. On duty for well over 30 hours without respite (their duty shift began at 7am on Saturday morning) and with the outcome still far from certain (who knew but that there would be further incendiarism that night), the decision was made to request reinforcements from the nearest available fire brigades. Lord Mayor O’Callaghan telegraphed his counterparts in Limerick (63 miles distant) and Dublin (163 miles) and the replies were swift and positive: help would soon be on the way. Members of Limerick Fire Brigade arrived by private car, laden down with fire gear, while Dublin dispatched its latest Leyland motor fire-engine with a crew under their chief officer, Jack Myers (great-uncle of journalist Kevin Myers). The Dublin contingent travelled on a specially commissioned train out of Kingsbridge (now Heuston) Station, accompanied by a large press corps. Each of the outside brigades performed sterling service, remaining on in Cork until the following Wednesday.

The cost of the night’s devastation amounted to over £3 million—in today’s money almost £143 million—not to mention the consequential losses or the estimated 2,000 thrown out of work, rendered homeless or otherwise severely discommoded. General Strickland’s report on the burnings was suppressed by the prime minister, Lloyd George, as it portrayed British conduct in Ireland in a very bad light. In so doing, he failed to recognise, it seems, that nothing inflates rumour as swiftly as concealment.

Harrassment and intimidation

Throughout Cork’s ‘night to remember’, firemen were harassed, intimidated and shot at by Crown forces. It was nothing short of a miracle that all missed vital organs, but four firemen had to be taken to hospital for treatment of bullet wounds. The brigade member working the Merryweather steam pump from the river suffered a shattered nose. (Although, unbelievably, there were no fatalities directly resulting from the fires, in the early hours of Sunday morning brothers Cornelius and Jeremiah Delany, along with their brother-in-law, were shot by police in their home, both brothers succumbing to their wounds.) The city streets were awash with precious water flowing uselessly from hoses that had been ripped open by bayonets. The military deliberately drove their lorries over the hoses until they burst. But not all Crown forces behaved badly; some actually helped the firemen to man the hoses, and one (perhaps a ‘Black and Tan’) saved the unconscious senior fireman, Ring (later, in 1928, chief officer), from a burning building. And a night not renowned for its levity did not pass without its moments of incongruous farce. Eighteen-year-old auxiliary fireman Michael Murphy, in a 1960 radio interview, recalled:

‘A Black and Tan jumped up on top of me. “Come on”, he says, “we’ll have a waltz”, and I put down the hose and I was waltzing with him. I noticed, him being a small man, he had a rifle … which protruded up under my chin. I said to him, “Here, boss, look at where that’s protruding, it’s rather dangerous”. He had a bottle in his pocket and I was afraid the trigger was hitting the bottle, and he said to me, “I’m Sunny Jim, and I never fired a shot in Cork!”, and with that he caught his rifle and threw it into the middle of Patrick’s Street.’

Pat Poland, a retiree from the fire service, is currently researching the history of Cork Fire Brigade in the twentieth century.

Further reading

Irish Labour Party, Who burnt Cork City? (Dublin, 1921).

P. Poland, For whom the bells tolled: a history of Cork fire services (Cork, 2010).

G. White & B. O’Shea, The burning of Cork (Cork, 2006).

Read More: Cork’s fire service