The Bruce Invasions of Ireland (1:1)

Published in Anglo-Norman Ireland, Bruce Invasion, Features, Gaelic Ireland, Issue 1 (Spring 1993), Medieval History (pre-1500), Volume 1

The initial latter of the Charter of Edward II to the City of Carlisle, 1316. The detail in this decorated initial shows the City of carlisle resisting siege by Robert Bruce in 1315. The Scots lacked siege technology;the catapault shown here was only one which the Scots possessed at Carlisle,whereas the defenders had seven or eight such machines.

The city of Dublin nevertheless prepared for the worst at the approach of the Bruce in February 1317

Introduction

These are the terms in which a near-contemporary described the Bruces’ invasions of Ireland (1315-18). Almost every subsequent commentator has remarked upon the unexpectedness and violence of this intrusion into Irish history. Accounting for the adventure has always been difficult, and a variety of explanations have been offered. The first is that the Bruces were inveigled into the quagmire of Irish politics by embassies from Irish kings; the second, that they envisaged a ‘Celtic’ alliance of Scotland, Ireland and Wales against England; the third, that the impetuous Edward Bruce, possessed by an overweening ambition to be a king in his own right, dragged Robert into this disaster; and the fourth, that the Bruces wanted to end the flow of men and supplies to the English and to divert it in their own favour.

AN IRISH INVITATION?

Taken individually, no one of these explanations is entirely convincing. Were the Bruces invited by the Gaelic Irish to become embroiled in their struggle against the Anglo-Irish colony? In Donal O’Neill’s letter of 1317 to Pope John XXII (the ‘Remonstrance’, in which, after a litany of English atrocities, Donal renounced his title to the kingship of Ireland in Edward Bruce’s favour) the implication seems to be that Edward Bruce had already established a military presence in Ulster. Yet given the internecine conflicts endemic in Gaelic society and the close links with Gaelic Scotland there is every possibility that Irish factions may have solicited assistance from a powerful neighbour. One narrative source, the Chronicle of John of Tynemouth, claims that Edward Bruce was indeed invited to intervene:

In this year [1314 (sic)] Edward Bruce, the brother of Robert Bruce, King of Scotland, … aspiring to the rank of kingship and having been invited most pressingly by a certain magnate of Ireland with whom in his youth he had been educated, gathered together an army and invaded Ireland with the support of the Irish.

Who was this magnate? Donal O’Neill is the most likely candidate; but we cannot tell for certain. There may, then, have been an invitation to intervene.

A ‘CELTIC’ ALLIANCE?

Did the Bruces aim to build a grand ‘Celtic’ alliance against England? In the thirteenth century there is evidence of a growing ‘Celtic’ consciousness in the Scottish islands, Ulster, the west of Ireland and Wales. The revolt of Brian O’Neill in 1260 found echoes of support in Wales and Scotland; and Edward I discovered that he could not suppress the revolts of the Welsh without causing unrest in Ireland. In the recent past Welsh and Scottish leaders had made formal complaints against the English to the Pope, which may have served as models for Donal O’Neill’s Remonstrance. Clearly the Bruces would have been keen to harness this consciousness for political ends. In 1307 Robert appealed for support to the Irish kings in the name of common ancestry, language and customs. A similar letter was also circulated in Wales, to which there was written a reply from the Welsh lord Gruffydd Llwyd addressed to ‘Edwardo illustrissimo Regi Hiberniae’. For a time during Edward’s Irish campaigns, Scottish privateers bade fair to dominate the Irish Sea, providing a potential means of communication between the disparate elements in the alliance. In Ireland the Scots showed interest in securing the ports of the Irish Sea; and in 1327 Robert was thought to be contemplating an invasion of Wales by way of Ireland. On the other hand one might expect the Bruces to be sufficiently familiar with the Celtic west to recognise that the unstable political structures of Ireland and Wales would be unreliable partners in the building of a grand coalition.

EDWARD BRUCE’S AMBITION?

The third possibility is that Edward Bruce’s personal ambition inspired the invasion. This is found in the epic poem The Bruce by John Barbour, a late but often reliable source. Edward Bruce stood a fair chance of becoming King of Scotland while Robert’s queen, Elizabeth de Burgh, was held prisoner in England. But she was returned to the Scots in the exchange of prisoners following the Battle of Bannockburn. The King and Queen of Scotland were reunited in January 1315; Robert could now expect an heir; and Edward’s hopes of succeeding in Scotland were suddenly diminished. An assembly of Scottish nobles met at Ayr in April 1315 and settled the succession. It was directly after this assembly that Edward embarked on his Irish expedition.

From an early stage, Edward claimed the kingship of Ireland. The bearer of such a claim is unlikely to have been satisfied with limited intervention, with ‘surgical’ strikes or with operations merely ancillary to Robert’s war in Britain. Edward’s claim to kingship may explain why the Scots in 1317 carried the war far from the east coast to the banks of the Shannon. But Edward’s ambition alone cannot account for every aspect of the Scottish intervention. Robert showed considerable commitment to the Irish adventure; and surely he would not have jeopardised his own kingdom merely to win Ireland for his brother. Robert lent Edward the services of Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray, one of his most trusted commanders. He made grants to encourage others to join Edward’s venture. And long after Edward’s death, Robert continued to intervene in Irish affairs. It cannot have been Edward’s ambition alone that fired the Irish adventure.

EXPLOITATION OF IRISH RESOURCES?

The fourth suggestion is that the Scots went to prevent the English from exploiting Ireland as a source of food and war material – and, if possible, to exploit it themselves. But how important was Ireland to the English war effort? From the victualling records of certain years it is possible to tell the extent to which the English depended upon Ireland for supplying Carlisle. In the 1310s Ireland supplied some 60 per cent of wheat supplies arriving at Carlisle. Oats was supplied in similar proportion, and also qantities of re-exported wine. Carlisle was the guardian of the English western march, the regional depot supplying castle garrisons at Dumfries, Ayr, Cockermouth and many minor fortifications. The English were thus heavily dependent upon Irish provisions for the defence of their western march. During Edward Bruce’s occupation of northern Ireland, in 1315-18, it became impossible for them to provision Carlisle from Ireland. But there were other factors at work: crop failures and famine in both England and Ireland; and privateers in the Irish Sea. Moreover the English were able, in spite of everything, to maintain their base at Carlisle during the invasion of Ireland. Whether the Scots diverted the flow of supplies from Ireland into their own land is another question. They are known to have extracted corn supplies from Ireland in 1315 and again in 1327. But it is unlikely that control of Ulster brought much in the way of food supplies. Edward Bruce’s invasion coincided with severe famine. In any case, he made no strenuous efforts to conserve food resources. In Ireland his forces followed the general practice common to all armies of the day, the wholesale wastage of agricultural productivity.

A WIDER STRATEGY?

It is possible that the linkage between Ireland and the struggle for the English western march went beyond the flow of supplies. The sources agree that the invasion took place in May 1315, just in advance of Robert Bruce’s attempt to take Carlisle by storm (22 July – 1 Aug.). Among the defenders of Carlisle were forty Irish archers; and among the force which eventually relieved the city was a large contingent of Irish hobelars (light cavalry) under the Earl of Pembroke. The author of the highly reliable Vita Edwardi Secundi alleges that a rumour of disaster in Ireland had a role in Robert’s decision to abandon the attack on Carlisle.

A false report meanwhile spread throughout England that our army in Ireland had scattered the Scots, that Edward Bruce was dead, and that hardly one of the Scots remained alive. Hence Robert Bruce, both on account of these wild rumours, and because he heard that the Earl of Pembroke had recently arrived … gave up the siege and set out towards Scotland.

The invasion of Ireland may then have been partly a reaction to the employment by the English of Irish soldiery on the western march.

The Bruces’ strategic conception may have been wider still. Carlisle and Berwick were the pivotal points of the war, each dominating the march, and each a vital supply depot. But the importance which the Scots attached to the capture of Carrickfergus Castle suggests that they saw this fortress in a similar light, as a third English forward garrison, protecting a vulnerable flank. Control of Ireland’s north-east coastline was also an advantage to the Bruces when dealing with the disaffected MacDougalls; for this alone the capture of Carrickfergus Castle may have been considered essential. If a ‘Celtic’ alliance was seriously contemplated, control of the Irish Sea was vital to communications between the allies. In this respect the activities of Scottish privateers on the Irish Sea may be highly significant. The privateers harassed the supply convoys bound for the western march; and even raided the English naval base at Holyhead, on the island of Anglesea.

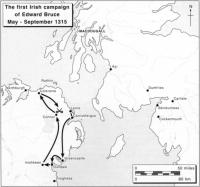

The initial campaign,confined to the environs of the North Channel,appears to have been co-ordinated firstly with Robert’s subjugation of hostile Argyll, and secondly with his attempt to storm Carlisle.

FIRST CAMPAIGN

(May- September 1315)

We have then a rag-bag assortment of explanations for the Scottish intervention in Ireland: an invitation, perhaps; thoughts of building an alliance of England’s western enemies; aspirations to kingship on the part of Edward Bruce; the tempting opportunity to sever English lines of supply to the embattled western march; and finally a Scottish strategic conception of the Irish Sea basin as a vulnerable flank along which England might be attacked. On the other hand Scottish war-aims in Ireland may not have been clear or well thought out; as we know from the present, a jumble of ill-considered ideas is often enough to have the marines sent in.

Edward Bruce’s initial expedition landed at Larne in May 1315, where he defeated a force of local gentry. At exactly the same time, Robert Bruce was subduing the MacDougalls of Argyll, on the shore directly opposite. Then as Robert turned his attention to Carlisle, Edward marched on Carrickfergus Castle. Robert tried to storm Carlisle; but Edward made no such attempt on Carrickfergus. Instead he negotiated with the Anglo-Irish garrison, which agreed to surrender if not relieved by Midsummer 1316. Soon after 6 June Edward had himself inaugurated High King of Ireland. The title, however, cut little ice with either the Gaelic or the Anglo-Irish. Leaving a force to keep the garrison in check, Edward marched south, through the Moyry Pass (where the Gaelic Irish tried to ambush him) to Dundalk, which he captured on 29 June. The forces of the colony were mustered belatedly. The Justiciar of Ireland and the Red Earl of Ulster advanced on him from the south. The Earl’s army included Gaelic allies, the foremost of which was Felim O’Connor of Connaught. The Justiciar’s army retired, leaving the Earl and his allies to pursue the Scots. Edward retreated far into Ulster, crossed the Bann at Coleraine, and broke down the bridge. Across the swollen river the two armies faced one another. Although famine conditions prevailed, the Scots were supplied by Gaelic allies – O’Neill, O’Cahan and O’Flynn. After a time the Earl’s force was severely weakened by the departure of O’Connor, who had been obliged to return to Connaught to partake in dynastic struggles. The Earl’s severely depleted force retired to Connor, where Edward Bruce defeated him on 10 September 1315.

This first campaign was the only one co-ordinated with an offensive in England; henceforth Scottish campaigns in Ireland tended to alternate with raids on northern England. They transferred veterans back and forth across the sea, concentrating attacks first in one theatre, then in the other. England, meanwhile, was almost paralysed by baronial unrest and by the increasingly severe famine. From Bannockburn in June 1314 to the siege of Berwick in the autumn of 1319 the English were unable to mount a major offensive. The counties and lordships, towns and even villages of northern England were at this time paying large sums in cash to the Scots in return for truces of limited duration so that Robert Bruce was finding it more profitable to restrain his forces in the north of England. But Robert’s forces had to be kept occupied, their hunger for booty satiated. There was scope for adventurism in Ireland; and in view of the situation in Britain, it involved no immediate sacrifice for Robert to place his men at the service of his brother. Nevertheless, he must have been aware of the tremendoous risks involved in committing forces to a new theatre of war.

Carrickfergus Castle was besieged by Edward Bruce from May 1315 to Autumn 1315. The starving defenders are said to have devoured eight Scottish hostages.

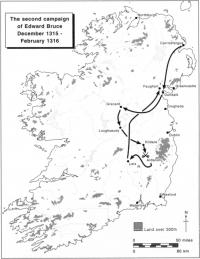

SECOND CAMPAIGN (December 1315-February 1316)

After a break of only two months to collect reinforcements, Edward Bruce embarked upon his second campaign, fought in mid-winter. Why the rush? Perhaps the Scots aimed to conquer Ireland before the English could recover from Bannockburn and the famine. It is also possible that Edward sought to co-operate with rebels in Wales. Llywellan Bren organised a rising in Glamorgan in January 1316, and Edward Bruce may have had prior knowledge of this. On 6 December he left Carrickfergus and marched to Dundalk, defeated Roger Mortimer, Lord of Trim, and then, guided by de Lacy enemies of Mortimer, he made his way through Meath. At Christmas Edward stayed at Loughsewdy; then he briefly besieged Kildare Castle. At Ardscull the leading Anglo-Irish magnates of Leinster turned out in force to oppose him on 26 January 1316 and suffered a second resounding defeat. The Gaelic Irish of Leinster were roused to action. They destroyed Bray, and together with the Scots, devastated Carlow. Even in the lordship of Desmond, the O’Donnegans, O’Conors and O’Kennedys rose in anticipation of Scottish victory. Edward’s southward thrust may have been directed against the ports for Wales – Waterford and Wexford – but lack of supplies prohibited further advance.

Edward Bruce’s depleted force returned to Ulster. At Carrickfergus, the Anglo-Irish garrison had been relieved by an expedition from Drogheda. During negotiations, the garrison seized thirty Scots and put them in irons as hostages. A Dublin chronicler reports that eight of the hostages were subsequently devoured as the starving garrison was reduced to cannibalism. The Carrickfergus garrison finally surrendered to the Scots in September 1316.

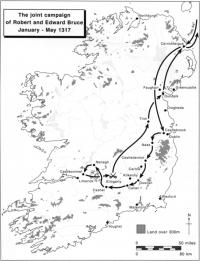

THIRD CAMPAIGN (January – June 1317)

The third campaign was conducted jointly by Robert and Edward. Robert had apparently decided that it was safe to put things ‘on hold’ in Britain, and he was impatient for victory in Ireland. In view of the famine (which made it impossible to assemble large armies) and of the lateness of the season, the English could be relied upon not to attack Scotland. The Scots landed and again marched southwards, through the Moyry Pass, and onto the plain of Meath. They advanced to Castleknock, within striking distance of Dublin itself. The citizens of the city prepared for a desperate defence. Suburbs were burnt down in order to deprive the attackers of cover; the bridge over the Liffey was broken; and the church of Saint Saviour was demolished to provide stones for barricades. Learning of these preparations, the Scots made no attempt to storm the city. Instead they moved off in a south-westerly direction, passing through a succession of villages in the valleys of the Barrow and the Nore, but without attacking the Anglo-Irish strongholds of Kilkenny and Carlow. They reached Callan by 12 March and turned westwards and arrived at Cashel a week later. By early April they were approaching Limerick. What had made the Scots cross to the Shannon? It appears that one faction of the O’Briens, the Clann Brian Rua, had earlier promised assistance to the Scots, and that the brothers marched to Thomond hoping to link up with an O’Brien rising. When they arrived at Castleconnell on the Shannon however, they found that Clann Brian Rua had been ousted by the rival faction, Clann Taidg, hostile to the Scots and waiting across the Shannon for a chance to attack. The Scottish army was by now being shadowed by an Anglo-Irish force under the Justiciar. Finally, a third hostile force sent from England under Roger Mortimer (who had been appointed Royal Lieutenant to deal with the emergency) had disembarked at Youghal on 11 April. The Scots were forced to retreat. They clashed briefly with the shadowing army of the Justiciar at Eliogarty. Many died from hunger and exhaustion on the march north. Robert returned to Scotland in June, leaving Edward still in control of an increasingly restive Ulster.

In the second campaign, Edward Bruce concentrated on wasting the heartlands of

the colony, and demonstrating the impotence of the Anglo-Irish administration.

Perhaps he also had in mind a thrust at Waterford and Wexford, to support the

rebellion in Wales.

FOURTH CAMPAIGN (October 1318)

Edward Bruce’s fourth and final campaign occurred in October 1318. He encountered an Anglo-Irish force at Faughart, near Dundalk; was defeated and killed. His corpse was quartered and the quarters dispatched to the four corners of Ireland. Carrickfergus Castle was recaptured by the Anglo-Irish on 2 December and Scottish power in Ulster was at an end for the time being. But the Bruce interest in Ireland continued.

A critical factor in determining the outcome of the war was the famine of 1315-22, caused by torrential rains which ruined successive harvests. The invasion was partly intended to prevent the use of Ireland as a source of supply for Carlisle and for campaigns on the western marches. The English were indeed prevented from invading Scotland from 1314 to 1319, but not by Edward Bruce. Rather, it was famine that kept Scotland safe from English invasion. This famine, common to Britain, Ireland and much of Europe, coincided exactly with the arrival of Edward Bruce. The Gaelic annals relate that:’during the three and a half years that this Edward spent in Ireland, a universal famine prevailed, to such a degree that men were wont to devour one another’.In Britain the famine helped the Bruces to victory, by rendering impracticable the standard English strategy of invading Scotland en masse. In Ireland, where the Scottish army suffered actual starvation at least twice, the famine appears to have assisted in their defeat.

Perhaps intended as King Edward Bruce’s royal perambulation of the country, the third campaign was certainly designed to impress the Bruces’ Gaelic allies. However, they were driven to inglorious retreat by the severity of the famine, and by the approach of superior forces.

ROBERT BRUCE’S CONTINUING INTEREST

Robert Bruce continued to intervene in Ireland after the defeat of his brother, even while practically on his death-bed; but he appears to have learnt a lesson from his brother’s failure. The old objective of alliance with Wales and Ireland he still pursued, but no longer as a primarily ‘Celtic’ one. Robert was now much more careful to woo the support of the Anglo-Irish, rather than of the Gaelic Irish. In 1327, on the death of the Red Earl of Ulster, Robert Bruce landed at Larne with an army. He was now seriously ill. Again it was rumoured that he intended to attack Wales by way of Ireland. An emissary was sent by the Justiciar to Bruce to dissuade him from proceeding any further. The mission was a success, and Bruce returned to Scotland.

This mysterious episode was probably an attempt to sound out the loyalty of the Anglo-Irish to the new regime in England. Queen Isabella and her lover Roger Mortimer had recently deposed and imprisoned Edward II, and they now threatened the Anglo-Scottish truce of 1323 by a renewal of war. Bruce was already attempting to destabilise the new English regime. He was behind the plots to have Edward II freed and restored to the throne. His nephew, Donald, Earl of Mar was more prominently involved; he and other Scottish agents were active on the Welsh marches at this time. Thus the plan to invade Wales by way of Ireland may still have been entertained by Robert Bruce; but his main object in coming to Ireland was to stir up trouble, by getting the Anglo-Irish to disown Isabella and Mortimer. At the declared intention of the Anglo-Irish to oppose him however, he was forced to back down. Before withdrawing to Scotland, Bruce exacted a truce from the men of the Earldom. In return for a supply of wheat and barley the people of Ulster were guaranteed a year’s peace by Bruce and his adherents. He returned to Scotland better equipped to face the imminent war.

Isabella and Mortimer were defeated, and forced to accede to Bruce’s terms for Scottish independence by the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton, known to the English as the ‘Shameful Peace’. Immediately after the settlement had been concluded, the dying Bruce returned to Ireland one last time, in the summer of 1328. He landed at Carrickfergus and escorted the Red Earl’s grandson and heir, together with his mother, to possession of the castle, and ensured that the new Earl was safely installed in his inheritance. Bruce now wanted to give every support to the Earldom of Ulster which had been seriously weakened by the war in Ireland. He was anxious that his infant son as King of Scotland would have a powerful ally in Ulster to check the power of the Gaelic lords of the Western Isles. The interests of the English and Scottish kings now coincided in Ulster; a strong Earldom kept at bay the Gaelic subjects of both. Bruce also took the opportunity of his presence in Ireland to make a final effort to detach the Anglo-Irish from the English. From Carrickfergus, he wrote to the acting Justiciar and his council, requesting that they meet him at Greencastle ‘ad tractandum de pace Scotie et Hibernie’ (to make a peace between Scotland and Ireland). But the Justiciar refused the invitation to make a separate peace. Having survived Edward Bruce’s forcible attempt to establish a separate political entity in Ireland, the Anglo-Irish were not now to be swayed by Robert’s diplomacy. With the death of Robert Bruce in 1329 Scottish intervention in Ireland ceased.

Suddane clyming, suddane falling, An high flood, a low ebb.

This pithy verdict, delivered by one of the later chroniclers on the career of Edward Bruce, applies equally to the rise and fall of the Scottish political interest in Ireland. The Bruces were uniquely placed to undermine the Anglo-Irish colony. The brief Scottish military hegemony in the wake of Bannockburn; revolt in Wales; the famine which paralysed the stronger nation – all these factors coincided to present the Bruces with the opportunity to carry the war into Ireland. But the precise motivation behind the Bruce intervention is difficult to fathom. A collection of weak motives may have combined to make the intervention in Ireland ‘a good idea for all sorts of reasons.’ But the fact that the Bruces risked so much in Ireland, that they persisted with such dogged determination, and that their adventurism was not imitated by other medieval rulers of Scotland compels the conclusion that the exact nature of the Bruce interest in Ireland remains a mystery.

Colm McNamee is a research officer for the Northern Ireland Parliamentary Boundary Commission.

Further reading:

A.A.M. Duncan, The Scots’ invasion of Ireland, 1315, in R.R. Davies (ed.) The British Isles 1100-1500 (Edinburgh 1988), 100-117.

Sean Duffy, The Bruce brothers and the Irish Sea world, in Cambridge Medieval Studies (Summer 1991), xxi, 55-86.

Robin Frame, The Bruces in Ireland, 1315-18, in Irish Historical Studies (1974), xix, 3-37.

James F. Lydon, The impact of the Bruce invasion, in Art Cosgrove (ed.), A New History of Ireland II, (Oxford 1987), 275-302.