THE BIG BOOKS

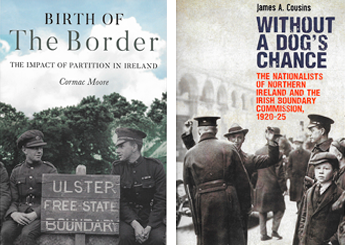

Published in Book Reviews, Book Reviews, Issue 4 (July/August 2020), Reviews, Volume 28BIRTH OF THE BORDER:

the impact of partition in Ireland

CORMAC MOORE

Merrion Press

€19.99

ISBN 9781785372933

WITHOUT A DOG’S CHANCE:

the nationalists of Northern Ireland and the Irish Boundary Commission, 1920–25

JAMES. A. COUSINS

Irish Academic Press

€24.95

ISBN 9781788551021

Reviewed by Martin Mansergh

It should be said at the outset that both books are excellent and informative, while coming at the subject from contrasting angles. Cormac Moore’s Birth of the border details the implementation and impact of partition from the Government of Ireland Act, 1920 (or fourth Home Rule Bill), through to the abortive Boundary Commission Report and beyond. James Cousins’s Without a dog’s chance is a graphic account of the hopeless position in which nationalists were placed with the creation of Northern Ireland and how different attempted escape routes, particularly the Boundary Commission, proved utterly illusory.

In both books, the prehistory of partition from 1886 to the 1918 general election, well covered in other works, is in the main only summarised. In the aftermath of the 1916 Rising, the failed attempt by Lloyd George on behalf of Asquith to fast-track 26-county Home Rule with the conditional agreement of both Carson and Redmond, which of course conceded the principle of partition, revealed two growing splits. One was between Ulster unionism and Irish (or southern) unionism, the latter totally opposed to partition, and the other was between Joe Devlin’s West Belfast base, which needed northern nationalism to retain a critical mass, and strongly anti-partitionist border nationalism.

While Redmond’s party were lambasted by Sinn Féin for accepting even temporarily the principle of partition, when it came to the Treaty or any alternative to it neither wing of Sinn Féin were able to do any better, even if one or two fig-leaves were temporarily provided to hide their political nakedness. The ostensible issue over which the 1917–18 Irish Convention, trying to find a way forward without partition, foundered was control of customs, with many nationalists, though not Redmond, determined to use protectionism to build up indigenous industry and unionists seeing this as cutting their established heavy industry off from British and imperial markets.

Today, a united Ireland is considered almost exclusively a nationalist/republican demand. Historically, it was also a fundamentally held unionist position. Twice in 1919 the Church of Ireland Gazette made the point that the general body of the church held by the Act of Union, ‘for the reason, amongst others, that it is the best means of preserving the unity of Ireland’, and that ‘the real champions of the unity of Ireland’ were ‘those who stood all along the line for the principle of Union’ (3 January and 24 October). Both the demand for Home Rule and the resistance to it were equally uncompromising. The price of self-government and the price of staying clear of it added up to partition and the creation of a border that neither side wanted, but it was a price that most were prepared to pay, as much preferable to the alternative. Yet Cardinal Logue was probably not alone in preferring continuation of the Union to local Orange rule.

Although presented as temporary, the border is fast approaching its centenary, with little sign of an early end to it, despite its attenuation. On the other hand, unionist boasts of its future permanence are contradicted by recurring crises of self-confidence.

The 1920–1 settlement left two minorities that felt abandoned, as both authors describe. The Protestants of Cavan, Monaghan and Donegal, some of them Covenanters, were told at an Ulster Unionist Council meeting in 1920 by Thomas Moles, MP for Belfast (Ormeau), in an emotive metaphor that conjured up the Titanic: ‘In a sinking ship, with life-boats sufficient for only two-thirds of the company, were all to condemn themselves to death because all could not be saved?’ The Irish News in the aftermath of the Treaty wrote in an editorial (24 December 1921) of wellnigh half a million nationalists: ‘They were Irish citizens twelve months ago. They have not surrendered their citizenship: but they cannot exercise it.’ That largely describes the situation since.

Cormac Moore is a Dublin-based historian, working with the City Council on its commemorative programme. He is a specialist in the history of splits, having previously written on President Douglas Hyde’s removal as GAA patron, to the fury of Eamon de Valera, for attending the Ireland–Poland soccer international in 1938, and also on the Irish soccer split. Given that Ireland had been a single entity under the Union, administered almost entirely from Dublin, Moore describes the breaking-up of public offices and organisations into two as ‘a gargantuan task’. Given the challenge of implementing Brexit in a much more complicated world, it is clear that reuniting Ireland, with the North rejoining the EU as well, would politically and technically be as daunting in reverse.

Despite window-dressing about ‘the essential unity of Ireland’, designed to appease southern unionists, the Government of Ireland Act, 1920, referred to as the ‘Partition Act’ by nationalists, started from the premise that there would be two subordinate parliaments in Ireland. Cabinet minister Walter Long’s committee produced it, without according the slightest legitimacy to the 1918 general election result in Ireland or to the rival Irish institutions established following the mass exodus from Westminster. Moore does not cite the late Peter Hart’s deconstruction of Long’s political stupidity in his contribution to Myles Dungan’s 2005 series Speaking ill of the dead. The Act, coupled with the threat of ‘crown colony government’, failed to stop the independence movement and only came into effect in Northern Ireland, where in the long run it did not work either. It was repealed as part of the constitutional settlement in the Good Friday Agreement. Originally, both the Council of Ireland and the Boundary Commission in the Treaty started as dummy unionist devices.

Both books highlight the sectarian violence that erupted in 1920 and 1922 in reaction to IRA attacks and the uncertainty of Northern Ireland’s position. The Belfast boycott, IRA cross-border raids in the first half of 1922 and the commandeering of unionist-owned buildings in Dublin did not arrest the consolidation of Northern Ireland, which, underwritten by the British, was able to defend itself. By agreeing to the Boundary Commission and then, before it could report, establishing customs posts along the boundary of the six counties, first Sinn Féin and then the Free State government tacitly accepted the principle of partition and helped institutionalise the line of it.

From a British perspective, partition was a success and a tool they used many times in the process of decolonisation, in the Indian subcontinent, Palestine, Cyprus, Aden and parts of Africa. Here, the ‘essential unity of Ireland’ survived outside politics, in the churches, in most sporting organisations (not just the GAA), in the trade union movement, with large autonomy for the Northern Committee of the ICTU, and in learned bodies such as the Royal Irish Academy. In 1938 the formation of the Irish Association to foster economic, social and cultural cooperation was primarily of unionist inspiration in some recognition of an Irish dimension, albeit a non-State one. From 1950 onward, then boosted by the Lemass–O’Neill talks and finally institutionalised in the Good Friday Agreement, north–south cooperation slowly revived, finally returning to the level envisaged in the 1920 Act and beyond.

James Cousins is Canadian and a senior policy adviser for the Ontario Ministry of Indigenous Affairs, with a Ph.D in history and a master’s degree in political science. His book is built round the concept of a ‘trapped minority’, developed by an Israeli anthropologist, Dan Rabinowitz, to describe the situation of Palestinians living inside the state of Israel. While belonging to a ‘mother nation’, they are trapped as a minority in a state dominated by others. They are marginal twice over, ‘once within the (alien) state, and once within the (largely absent) mother nation’. While not an exact parallel, as Israel, unlike Northern Ireland, is a state, Without a dog’s chance describes in these terms the experience of the nationalist minority in Northern Ireland, between its inception in 1920 and the border being locked down in 1925. His main sources are nationalist newspapers, the Devlinite Irish News with its religious motto Pro fide et patria and the Sinn Féin-oriented Derry Journal and Fermanagh Herald,on the assumption that they broadly reflected the views and reactions of their readership.

The few nationalists remaining at Westminster had no influence over the Government of Ireland Act, Devlin declining to put down amendments. While the mooted Southern Irish Senate and the actual first Free State Senate had generous (ex-)unionist representation, the Northern Ireland Senate simply replicated the unionist lower house majority. Meanwhile, Belfast shipyard workers, reacting to IRA attacks elsewhere, engaged in the expulsion of thousands of Catholic shipyard workers, encouraged by Carson. The retaliatory Belfast boycott completely overestimated its impact on the northern economy and simply hardened partition. Denis McCullough, one-time leader of the Belfast Volunteers, was forced to close his ‘purely republican’ bagpipe business! High-profile Ulster TDs like Eoin MacNeill, Ernest Blythe and Seán MacEntee, or lawyer Kevin O’Shiel, may have been advisers on the North but they did not represent it.

Devlin abstained from the Westminster debate on the Treaty, but nationalists in the North looked with a jaundiced eye on the Treaty split and the slide into civil war. Collins’s underhand encouragement of attacks to undermine the border as a diversion backfired. Bonar Law demanded action after Sir Henry Wilson’s assassination, saying that he had wrongly believed that those who had signed the Treaty accepted that Ulster could never be brought in except by consent. The civil war weakened the Irish negotiating position on the Boundary Commission and let Northern Ireland off the hook. The North-Eastern Boundary Bureau’s attempts to press for plebiscites came too late. The finisher for the Free State government was the Boundary Commission recommendation that parts of East Donegal be transferred to Northern Ireland. The report was suppressed, the Council of Ireland abolished and the border recognised, set against the prize that the Free State’s contribution to the British national debt was written off. This provided no comfort to nationalists left in a position of impotence until the era of civil rights.

Martin Mansergh is a former politician and Northern Ireland adviser.