The Battle of Aughrim

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Issue 3 (Autumn 1995), Volume 3

Godard De Ginkel, first Earl of Athlone by Sir Godfrey.

(courtesy of The National Gallery of Ireland)

Aughrim need never have been fought. That it happened was due to the Frenchman Charles Chalmont, Marquis de Saint-Ruhe, generally referred to as Saint Ruth who assumed the post of Marshal-General of Ireland, in May 1691. Saint-Ruhe’s command was confined behind the Shannon to Connacht following the 1690 campaign in which William of Orange had failed to end the war. The Williamites were now commanded by another Dutchman, Godard de Ginkel.

Jacobite morale high

Jacobite morale remained high, especially after Patrick Sarsfield’s raid on the Williamite artillery train at Ballyneety. Sarsfield continued to inspire the Irish throughout the winter of 1690/91, and ensured that the Williamites would not cross the Shannon. Pivotal to the Shannon defence was Athlone town which had withstood siege in 1690. With strengthened defences it could do so again in 1691 but, thanks to elementary blunders by Saint-Ruhe, Athlone fell after ten days.

The retreating Irish army had lost half its infantry through desertion when it reached Ballinasloe. Saint-Ruhe, suffering the agonies of a humiliated commander, considered taking Ginkel on in a decisive pitched battle. His generals were unhappy about this prospect, especially as Tyrconnell, King James’s viceroy, had ordered a return to Limerick where, with strengthened defences, the Irish could hold out as in 1690, forcing the Williamites into another campaigning year in 1692. Although some generals supported Saint-Ruhe the majority disagreed; he finally issued orders for the army’s dispersal to Galway and Limerick.

General d’Usson was sent to Galway; General Wauchope, still not fully recovered from injuries at Athlone, to Limerick to join Tyrconnell; and Sarsfield to Loughrea to oversee arrangements for the march. Saint-Ruhe remained at Ballinasloe where morale improved as deserters rejoined. The Frenchman revised his strategy: after all, he commanded the army and believed himself the best general in Ireland. He ignored warnings that giving battle in the field would be to throw away all of Ireland. Without Sarsfield, Wauchope and d’Usson to restrain him, Saint-Ruhe began to lay plans. Reconnoitring the area about the army’s camp, he selected his ideal ground for a battle, a hill five miles away called Kilcommodon below which lay the village of Aughrim.

Ginkel was uncertain about Irish intentions. Irish cavalry prevented Williamite patrols from closing on the main body of the Jacobite army. The Dutchman also needed to replenish his powder and ammunition before advancing and had to protect his supply routes against interdiction by Sarsfield’s cavalry. So he consolidated at Athlone and covered his lines of communication. Saint-Ruhe bolstered his army’s morale, creating a personality cult around himself with bloodthirsty promises of what the army would do to its foes, and used Catholic clergy to create crusading zeal.

A portrait of gentleman, possibly Patrick Sarsfiled, Earl of Lucan. Attributed to Jon Riley. (courtesy of The National Gallery of Ireland)

Crusading fervour

Irish scouts finally reported to Ginkel at Ballinasloe from where, on 11 July, Williamite cavalry patrols found the Irish at Aughrim. Saint-Ruhe had chosen the ground and now addressed his army, some 20,000 strong, telling them that they would

bear no longer the reproaches of the heretics who brand you with cowardice, and you may be assured that King James will love and reward you, Louis the Great will protect you, all good Catholics will applaud you, I myself will command you, the church will pray for you, your posterity will bless you, God will make you all saints and his holy mother will lay you in her bosom.

At daybreak on Sunday 12 July, Ginkel’s army crossed the River Suck. It was misty and the Williamites moved cautiously until within sight of their foes. The Irish waited confidently. Their position was described by Robert Parker:

The right flank was covered by a large morass, which extended along their front till it passed their centre. From thence to the castle of Aughrim (which covered their left flank) were a parcel of old garden ditches, within which was posted their left wing of Foot; and they had a body of Horse drawn up on a plain behind these ditches.

Another Williamite commentator, Story, wrote that the Irish dispositions:

showed a great deal of dexterity in M. Saint-Ruth in making choice of such a piece of ground as nature itself could not furnish him with a better, considering all circumstances; for he knew that the Irish naturally loved a breastwork between them and bullets, and here they were fitted to the purpose with hedges and ditches to the very edge of the bog.

The Frenchman had indeed made good use of the terrain to overcome his soldiers’ lack of experience of open manoeuvre. Although not adept at staying in line of battle, or forming a square to resist cavalry, they would fight hard from the cover of natural breastworks. And it would be very difficult for cavalry to approach them: horsemen would move only across the causeway through the village, or by a ford on the far side of Kilcommodon; Saint-Ruhe had cavalry covering both approaches with infantry on the hill between. The Irish were confident: Mass had been celebrated and crusading fervour permeated them.

Saint-Ruhe intended Ginkel to make a frontal attack which would mean the Williamites approaching his right flank over the ford and his centre through the bog. The left, he felt, was almost immune from attack as Aughrim castle dominated the causeway. Once the Williamite attack had been repulsed, Saint-Ruhe would launch his cavalry across the causeway to hit the foe in the flank; in the ensuing confusion the Irish army would advance, rolling up its enemy. But it would be as difficult for the Irish to counter-attack effectively as it would be for the Williamites to break the Irish line and Saint-Ruhe could never hope to destroy Ginkel’s army; he could only delay its advance.

Dispositions for battle

Dispositions for battle

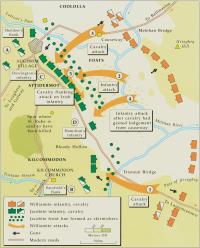

Saint-Ruhe created divisions under William Dorrington, John Hamilton, Patrick Sarsfield and Dominic Sheldon. The former pair commanded infantry divisions in the centre under Saint-Ruhe’s eye; Sarsfield and Sheldon commanded mixed formations of cavalry, dragoons (troops who moved about on horseback but who fought on foot) and infantry. The sole reserve was Galmoy’s regiment of cavalry, located behind the hill backing the Irish centre. In committing almost everything he had, Saint-Ruhe risked all. Ginkel had no idea that the soldiers he could see arrayed against him represented the entire Irish army at Aughrim.

Sarsfield and Sheldon were stationed on the wings, the former on the right which was probably the army’s most vulnerable area as firm open ground on either side of the Tristaun stream might allow an outflanking move. The greater body of horsed soldiers was therefore under Sarsfield’s command with Saint-Ruhe’s deputy, Lieutenant-General de Tessé, a highly-experienced cavalry commander, also on that flank.

On the left, 200 musketeers in the castle ruins covered the approach from the causeway. Two infantry battalions were nearby, close to where attacking cavalry would debouch from the causeway. Brigadier Henry Luttrell commanded four dragoon regiments on open ground behind the infantry. Four cavalry regiments were deployed further back; Sheldon was to hold these ready for the final charge to break the Williamites.

Battle plans

Battle plans

The armies faced each other throughout the morning, Ginkel studying the Irish dispositions and the ground. The lie of the land and their dispositions gave the Irish tactical advantages: they had numerical advantage in infantry. The Williamites had more cavalry who were of limited use: the bog meant that they could advance only via the causeway against the Irish who were holding Aughrim and the castle. The Dutchman conferred with his senior staff and it was the Scot, Hugh Mackay, who suggested a battle plan.

Mackay noted that most of the Irish cavalry was on Sarsfield’s flank: therefore Saint-Ruhe was most concerned for his right. A major attack on Sarsfield’s division should cause Saint-Ruhe to move troops there from the left. A simultaneous infantry advance through the bog and a lodgement, even briefly, on the Irish side would cause further draining of soldiers from the Irish left, at which stage an attack could launched at the Jacobite left to clear causeway, castle and village, thus opening the way for English cavalry to cross the causeway and outflank the Irish infantry.

Mackay’s strategy dictated the course of the battle which began as separate clashes and resolved into the climactic destruction of Saint-Ruhe’s army. Fighting began in late afternoon, preceded by skirmishing which may have begun on Sarsfield’s flank; Sarsfield’s patrols had engaged Williamite scouts across the ford on his front. Since the Williamites needed to clear the area in front of them so that the main body of the army could deploy, skirmishing intensified with more and more Williamite troops drawn in. Matters were developing according to plan for Saint-Ruhe: he wanted the enemy to engage his right where they would have to force Sarsfield’s division back.

Ginkel’s cavalry stalemated

Facing Sarsfield were Ginkel’s continental cavalry regiments. Some 1,500 men charged across the ford at 6 o’clock onto the Irish bank and opened the largest cavalry battle of the war. Additional Williamite cavalry crossing the ford forced Sarsfield’s men back to the second line of cavalry where Ginkel’s cavalry were stalemated by Sarsfield’s cavalry and dragoons, and bombarded by Irish artillery.

As the cavalry clashed, Williamite infantry advanced. Soldiers lost their formation in the boggy ground, wading through waist-high mud and water. Nor could they see their enemy who lay behind hedges and banks until their targets were close enough for devastating fire. Story recorded that some did not believe that the Irish had any men in that place…but they were convinced of it at last, for no sooner were the French and the rest got within twenty yards or less of the ditches than the Irish fired most furiously upon them.

Williamite retreat

Once on solid ground the Williamites dashed forward. But the Irish had pulled back to the next defensive line. Ginkel’s infantry were still exposed to effective Irish fire. Stuck without cover, or still struggling through the bog, the Williamite infantry could not remain where they were and survive. Their lodgement was brief: the Irish had maintained their order and, as their enemies milled about in confusion, Jacobite infantry charged. The Williamites fled into the bog, pushing their reserves before them.

On the right, Williamite infantry under Mackay, trying to secure the causeway for cavalry, had also been repulsed. Hesse’s Danish-Dutch brigade had followed Mackay on Ginkel’s orders but was forced to withdraw, leaving Mackay’s command dangerously exposed. On the extreme left, La Melloniere’s brigade took the full brunt of Irish fury as John Hamilton’s soldiers smashed into the unfortunate Danes and Huguenots. The downhill charge of the Irish had broken the Williamites and the Irish chased their foes across the bog.

Bird’s-eye view of the field of Aughrim, 12 July 1691,

adapted from Story’s Continuation of the Impartial History…(1693).

‘The day is our’s’

As La Melloniere’s men had been advancing, the Irish artillery had switched their attention to them from the cavalry whose commander, the Huguenot Major-General La Forest, called for reinforcements to force his way through the Irish cavalry and support his infantry. La Forest wanted to move left to firmer ground but, even reinforced by Major-General van Holzapfel’s division, could not do so. The Williamite charge was pushed back by Sarsfield’s division, now strengthened with men from Sheldon’s flank. Without room to manoeuvre, La Forest’s men lost heavily; among the dead was van Holzapfel. Fighting continued with the Williamites being bested by the Irish in every effort to advance. A delighted Saint-Ruhe claimed, ‘Le jour est a nous, mes enfants!’

The only Williamite element not yet committed to battle was the English cavalry, now Ginkel’s only opportunity to make an advance. Thanks to Sarsfield, this would have to be on the right, by the causeway. But that route was not yet clear; Mackay’s infantry had not secured the causeway.

During the battle Dorrington had moved two infantry battalions from the Aughrim end of the causeway to strengthen the centre. Ginkel and Mackay noted that these units had not been replaced, presenting an opportunity to exploit the causeway and beyond. However, the cavalry officers were unenthusiastic about advancing as they did not know where the bog ended. One refused Mackay’s order to reconnoitre since he would be riding within musket range of Irish infantry in Aughrim village and castle. A furious Mackay tried to do the job himself but was thrown by his horse and injured.

English ball for French flintlocks!

Meanwhile, Ginkel had issued orders to Ruvigny, commanding the cavalry on the right, to advance. Ruvigny assigned the task to Villiers’s brigade which he joined himself. By now brigade was a misnomer for Villiers’s command: so many had gone to reinforce La Forest that only six squadrons of cavalry and dragoons remained. With this small force Ruvigny and Villiers moved forward.

It appeared a foolish, even suicidal, move and Colonel Walter Burke’s men in Aughrim castle stood ready to emphasise the folly. Although unable to stop the English completely, they could account for many of them as the cavalry would pass only some forty yards from them. As Burke’s men opened fire, the cavalry raced forward; the dragoons dismounted and returned fire to cover their cavalry comrades. Then one of those catastrophes that litter the pages of military history struck the Irish. Already low on ammunition they opened ammunition boxes to find that the balls were for English muskets, too big for their French flintlocks.

In desperation the Irish soldiers seized anything that might fit their muzzles—uniform buttons, pebbles, even broken wooden ramrods. Their fire died away and the cavalry crossed the causeway ready to meet the infantry guarding the road. But the two battalions were still absent. All that faced the English were Luttrell’s dragoons who opened fire on the leading enemy troops; Luttrell then pulled his men back to await cavalry reinforcements. As Luttrell’s men withdrew, Ruvigny ordered a charge: the dragoons beat a hastier retreat than intended, pulling back even further in panic. Sheldon’s cavalry was by now reduced to about two regiments as many squadrons had gone to reinforce Sarsfield.

In the balance

More English cavalry had crossed the causeway but had not secured their positions and were vulnerable to counter-attack, a fact recognised by both Ginkel and Saint-Ruhe. Ginkel ordered some of the cavalry facing Sarsfield to join their English comrades before the Irish cavalry pushed back or, worse still, annihilated the English. Saint-Ruhe was not taken aback; the chronicler of A Light to the Blind described him as being elated. Messengers were sent to Galway and Sheldon with orders for the left wing of his horse, that had been idle all the day, to go and oppose [the English], which he knew was easily done, and therefore he continued his joy, as being sure of his point….the victory is so certainly in the hands of the Irish, that nothing can take away but the gaining of that most perilous pass by the castle of Aughrim; that the defending of it is so easy that a regiment may perform the task. …four regiments of horse and four of dragoons might make the passage impossible.

Medal commemorating the battle of Aughrim by J. Smeltzing. (National Museum of Ireland)

Saint-Ruhe’s decapitated

Saint-Ruhe ordered the Life Guards from Sarsfield’s wing to follow him as he rode to lead the cavalry charge that would destroy the English cavalry. Riding off to the left, he told his men: ‘They are beaten, let us beat them to the purpose’. Those were Saint-Ruhe’s last words: pausing to give orders to an artillery battery he was decapitated by a cannonball.

The Life Guards’ officers kept the news of Saint-Ruhe’s death from the rest of the army. It was a disastrous decision: Sheldon’s men, awaiting Saint-Ruhe’s orders, became ever more nervous as the general failed to appear. Sheldon would not order a charge as the enemy cavalry were in Dorrington’s area of responsibility and he, Sheldon, needed Saint-Ruhe’s authority to order his men there. Worse still, Saint-Ruhe had committed one of the greatest sins a commander can commit: he had not divulged his battle strategy to his senior officers. Not even Sarsfield knew the plan. Sheldon waited in vain for his general and orders.

Luttrell’s men faced the English cavalry with no prospect of support. As enemy numbers increased the dragoons were being outnumbered; an English attack now would lead to slaughter. Luttrell ordered a retreat and his dragoons rode off the battlefield, placing Sheldon in a very dangerous position as he had insufficient men to beat back the enemy. Ruvigny ordered the leading English cavalry regiments to tackle Sheldon’s troops while the remainder took the Irish infantry in the flank.

Irish infantry crumble

It seems that, on that left flank of the infantry, the second line had been removed thus weakening opposition to the English cavalry. It hardly mattered much; the missing soldiers would have made little difference. The Irish defences had been designed to protect against a frontal, not a flank, assault, and the cavalry arrived so suddenly that there was no time to change positions, nor did the training and experience of the Irish infantry allow battalions to form platoons or squares to meet the cavalry, even had there been time. Cavalry charged into the infantry who ran for the hilltop as the horsemen penetrated even further.

De Tessé assumed command of the Irish army on the general’s death but was overwhelmed by the cavalry charge into his infantry from their left. Having been moved to Dorrington’s division, left of the centre, de Tessé had been concentrating on the infantry battle. When he heard of Saint-Ruhe’s death it was too late to do anything effective. He rode towards Sarsfield and ordered the first two squadrons of cavalry that he met to follow him to tackle English cavalry already in the Irish lines. By then Sheldon had gone; there were no other Irish horsemen about. Valiantly, de Tessé formed up his two squadrons and led them in a downhill assault against a numerically superior enemy. The general stopped three bullets, one round striking him in the face, another entering his chest. Lucky to be alive, he was led from the battlefield by an aide-de-camp.

Dutch print illustrating the battle of Aughrim, 12 July 1691.

Sarsfield’s efforts

Engaged for hours against a stronger enemy cavalry force which he had bottled up, Sarsfield knew nothing of the English breakthrough, nothing of Saint-Ruhe’s death, nor of the fate of de Tesse, nor of Sheldon. As daylight faded and rain began to fall he could hardly have been expected to see, or hear, what was happening to his left.

Eventually the situation became clear to Sarsfield. To his left, Irish infantry were giving way to enemy cavalry. Ginkel’s infantry had re-crossed the bog and were advancing, unopposed, up Kilcommodon Hill. Sarsfield knew that the only Irish reserve had been Galmoy’s Horse, another major error on Saint-Ruhe’s part, for it is a basic principle of war that a commander should always have a reserve: Galmoy’s regiment was not a real reserve, capable of changing the course of the battle. Sarsfield had no idea whether Galmoy’s men had been committed; their position was hidden from him by the hill. He could only act as he thought best. All day Williamite cavalry had outnumbered him but had been unable to better him; now he had to slow the advance of that cavalry and detach squadrons to support the Irish infantry. But, no matter what he did, the battle was lost for the Jacobites.

Sarsfield sent his cavalry in successive checking charges against each formation of La Forest’s cavalry, but his efforts to help the infantry were all but vain. Enemy cavalry and infantry had virtually surrounded the Irish foot soldiers. Save for Sarsfield’s division, the battle had become a rout. Those Irish infantry who stood their ground and evaded the cavalry were shot by advancing enemy infantry. The blind fury of battle had taken over and Irish soldiers who survived the killing fields of Aughrim did so either because fading light, or rain, helped them slip away, or because they used the bogs to escape, or because of Sarsfield’s efforts.

The cost of defeat

One English commentator wrote that Sarsfield ‘performed miracles’ and seemed to have a charmed life as he survived in spite of taking many risks. The Jacobite commentator of A Light to the Blind wrote that

only the Earl of Lucan [Sarsfield], with some troops [of horse], and the Lord of Galmoy, with his regiment, did good service in covering their retreat as prosperously as so small a body could do. This and the arriving night and the morasses brought them off indifferently well. ‘Twas their officers respectively that suffered most.

Aughrim castle fell that evening: the battle was over. Just when it had appeared that the Irish ‘were mowing the field of honour’, victory turned into defeat. Some 7,000 corpses littered the battlefield. Story put Irish losses at 7,000 dead with Williamite dead at less than 1,000. Both figures are exaggerations: his low assessment of the Williamite losses is based on his knowledge of the English dead, but continental regiments had suffered heavily in the infantry battle. Robert Parker, who served under Mackay, has probably the most reliable estimate of dead: he wrote that ‘near four thousand [Irish] were killed’ while Ginkel lost ‘above three thousand killed and wounded’.

The Irish also lost most of their equipment as the Williamites overran their camp. And the leadership of the army was destroyed: two brigadiers and nine colonels were killed; two major-generals, Dorrington and John Hamilton, a brigadier and nine colonels were captured. Hamilton later died of wounds. Eighty priests were among the dead. Defeat would have been a psychological blow in any circumstances: coming when victory seemed assured it was all the more difficult to accept and understand. The Irish knew they had fought well and bravely, beating back the enemy several times, inflicting heavy casualties, yet still they had been defeated. Why?

Who’s to blame?

Tyrconnell blamed Saint-Ruhe for engaging in battle. But blame also lay with others. Whoever supplied the wrong ammunition to Burke’s men at the castle was incompetent, but the English cavalry would probably have been able to get by anyway; they ought not have been able to pass the block of two infantry battalions at the causeway exit. Dorrington, who removed those battalions, should have replaced them, or sent them back when the situation in the centre eased and must, therefore, stand guilty of negligence. With Dorrington’s men absent, the English cavalry were met by Luttrell’s dragoons. Henry Luttrell has become a convenient scapegoat for the debacle at Aughrim; it has even been suggested that he ‘sold’ the passage for gold. Although Luttrell later became disenchanted with the Jacobite cause, no contemporary evidence suggests he was suffering disenchantment at Aughrim.

In terms of military incompetence, of failure to use initiative, of failure to anticipate orders, Dominic Sheldon has few equals: he saw the danger facing Luttrell yet did nothing but await orders. He must have known that Saint-Ruhe would have wanted him to charge the English, and that such a charge would have maintained Irish supremacy. No one deserves high command if he cannot act on his own initiative in such circumstances. The writer of A Light to the Blind saw this clearly

the commanding officers of the left wing, by abandoning their station without compulsion…were either traitors to their king and country, or…they showed a barbarous indifference for the safety of their friends and countrymen; or…were notorious cowards. And so let them keep their priding cavalry to stop bottles with.

Two days later, aware of the details of what had happened at Aughrim, Tyrconnell sent three messengers to France to appraise James of the situation and seek French reinforcements. He also prepared to hold Limerick. Of his messengers to France, only one survived.

The Irish army retreated to Limerick where Tyrconnell died. Sarsfield assumed command and, aware of the war’s cost to Ireland’s people, decided that the Jacobite cause would be better served by taking Irish soldiers to the continent to prepare for an invasion of the British Isles. And thus came about the Treaty of Limerick, and the end of the War of the Kings, in October 1691.

Richard Doherty in a military historian.

Further reading:

G.A. Hayes-McCoy, Irish Battles: A military history of Ireland (Belfast 1989).

W.A. Maguire (ed.), Kings in Conflict: The revolutionary war in Ireland and its aftermath 1689-1750 (Belfast 1990).

R. Shepherd, Ireland’s Fate: The Boyne and after (London 1990).

P. Wauchope, Patrick Sarsfield and the Williamite war in Ireland (Dublin 1992).