The Abergele mail train disaster, 1868

Published in 18th-19th Century Social Perspectives, Features, Issue 6 (November/December 2018), Volume 26In the peaceful setting of St Michael’s churchyard in Abergele in north Wales, just off the busy A55 road, there is a memorial to the 33 victims of a horrific railway accident who were buried in a mass grave there in August 1868. It was the worst rail disaster up to then, and the graphic newspaper descriptions of what occurred were profoundly shocking; it also had a devastating impact on some leading Irish families.

By Bryan MacMahon

On 20 August 1868, at 7.30am, the Irish mail train left Euston Station, London, for Holyhead. Among its notable passengers were the duchess of Abercorn, wife of the lord lieutenant, accompanied by five of her children, who were returning to Dublin after the summer in London, Lord Farnham (Henry Maxwell) of Cavan and his wife, and Viscount Castlerosse of Killarney. The Irish mail was the wonder of the railway age: it had been operating since 1860 and was the fastest train in use, capable of reaching 60 miles per hour. It was very popular with travellers to and from Holyhead, many of them people of status and wealth, and it had two special carriages where mail was sorted en route. On this occasion, none of the passengers could have had any premonition of the disaster that awaited the train in north Wales.

When it arrived in Chester at 11.30am, four carriages were added at the front. Most of those who boarded there would have chosen these carriages, as they provided more seating options—a casual decision that proved to be a fateful one. Twenty minutes ahead of the train’s schedule, a regular daily shunting operation of a goods train into a siding was taking place at Llanddulas. During this procedure, a brake-van and six wagons from the goods train were detached and left stationary on the main line. While the shunting work was proceeding, the six wagons started to run downhill on the main line, into the path of the approaching mail train. The nature of the goods on two of the six wagons would turn what might have been a mere collision into an inferno: they were carrying 50 wooden barrels containing 1,800 gallons of paraffin.

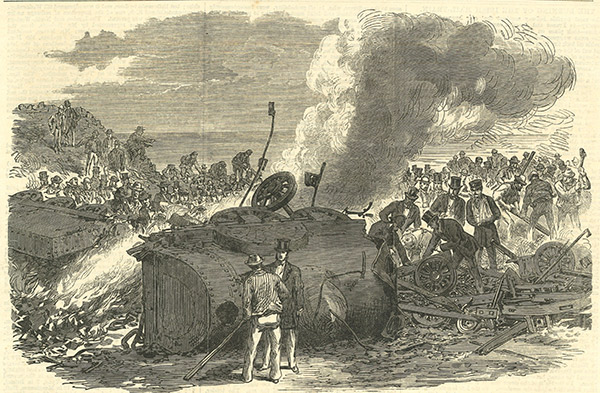

Above: The scene at Abergele as sketched an hour and a half after the crash. (Illustrated London News supplement, 29 August 1868)

At a bend in the line just past Abergele, the driver of the Irish mail, Arthur Thompson, saw the goods wagons approaching; he anticipated what was about to happen but could not avoid the collision. The train was travelling at about 30 miles per hour. Thompson applied the brakes, put the engine into reverse and jumped clear; he died of his injuries a few months later. No blame was attached to him in the inquiry that followed the accident.

‘An all-enwrapping, all-consuming flame of fire’

As soon as the impact occurred, there was a huge explosion and the front carriages immediately became engulfed in a great fire. According to the Illustrated London News:

‘A new horror has been added to the number of horrors to which railway travellers are exposed. A rush down the crater of Mount Vesuvius into the fiery gulf beneath it could hardly be more appalling.

A momentary crash—a dense cloud, blacker than night, of suffocating vapour—an all-enwrapping, all-consuming flame of fire—and between thirty or forty human beings comprising old and young, noble and simple, all rejoicing a minute before in life and in its pleasures, most of them probably gazing with delight upon the picturesque scene through which they were passing, were transformed into a heap of charred and undistinguishable remains.

Not a cry escaped them—not a struggle was observed—not a chance of rescue was given; death and destruction overwhelmed them in an instant leaving to their surviving relatives scarcely a memorial of their former existence.’

Initially there was brief speculation that the incident was caused by a Fenian bomb, especially when it became known that the viceroy’s family was on board, but that theory was quickly discounted. One notable feature of the accident was that there were no wounded: there was a clear demarcation—death for all those in the front four carriages and survival for those in the rear. The survivors included the Abercorn party and Viscount Castlerosse, but not the Farnham couple.

Identification

Above: The funeral in Abergele churchyard. There were emotional scenes when the coffins were placed in a grave 60ft long. (Illustrated London News supplement, 29 August 1868)

The graphic reports of the Abergele incident still have the power to shock in their depiction of the horror:

‘Thirty-three persons of all ages have been changed from living healthy bodies to a whole mass of shapeless charred objects in a few hours. Not a single one of the remains presents anything like a human body. Not a single head adorns a single human relic. Feet and even legs are unknown. All seem to have been doubled up in their last agonies …’

The Freeman’s Journal report began: ‘I have just returned from witnessing one of the most appalling and heartrending spectacles it is possible for the imagination to conceive’. It described dead bodies ‘burnt to cinders’ and ‘literally roasted alive’. The only consolation for grieving relatives was that death was instantaneous and the victims did not suffer prolonged agony. Ten male, thirteen female and other undistinguishable bodies were recorded, and estimates of the number of dead varied until a final total of 33 was established.

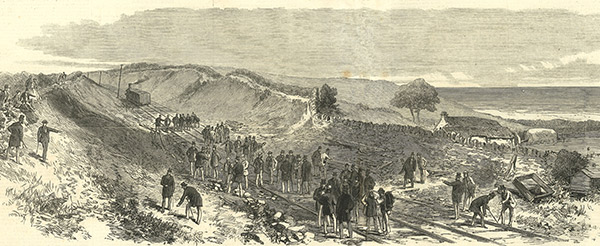

Above: The jury visits the scene of the accident. (Illustrated London News supplement, 29 August 1868)

Inquest and inquiry

At the inquest, which was held in the Bee Hotel, the scrupulous coroner was concerned about identification: ‘I do not care if the limbs are gone but I must have a body and a head … What should we do if we held an inquest on a person who should happen to be alive after all?’ The issue of individual identification delayed the burials, adding to the agonies of relatives. The coroner urged ‘extreme caution’, and at first did not accept that a watch with the Farnham crest attached to a body was proof of identification, as he said that Lord Farnham might have lent the watch to another person. Eventually, only three bodies were identified and it was decided that all the victims should be buried in a mass grave in Abergele churchyard. But there were only 31 coffins, each marked by a number rather than a name. Distraught mourners from all over the two islands, led by the new Lord Farnham, brother of the deceased, gathered in Abergele church for the funeral on 25 August, and there were emotional scenes when the coffins were placed in a grave 60ft long. Funeral expenses were paid by the London and North Western Railway Company (LNWR).

An inquiry followed and two brakesmen of the goods train were charged with manslaughter for not properly securing the goods wagons on the line. They were ultimately acquitted in the courts. LNWR was heavily criticised by the inquiry, especially for not having proper procedures in place for shunting the goods train. Communications were also found to be inadequate, as it was not possible to send a warning signal down the line to the approaching train. The inquiry led to improvements in rail safety standards, and new regulations were introduced with regard to shunting operations, signalling between stations and the conveyance of explosive materials. All these changes were costly, however, and were only implemented over a long period.

Memorials

The memorial erected in St Michael’s churchyard was funded by LNWR. It is well tended today, with the names of the victims clearly legible. They included three businessmen from Blackburn, two brothers and their brother-in-law, who were on their way to Killarney for a holiday. They almost missed the Irish mail in Chester, except that they had bribed the driver of their connecting train to go at top speed. As well as Lord and Lady Farnham of Cavan, several members of their household staff were among the dead: Elizabeth Strafford, companion; Mary Ann Kellett, maid; Charles Cripps, footman; and Edmund Outen, valet. A statue in memory of Lord Farnham was erected by his tenants and now stands outside the Johnston Central Library in Farnham Street, Cavan. The Farnham family motto was Je suis pret (‘I am ready’).

A well-known Irish judge, Walter Berwick, was another high-profile victim. He was first reported as having survived, but when a pocket knife was found with ‘Berwick’ engraved on it his fate was confirmed. He was chairman of the quarter sessions of the east riding of Cork from 1847 to 1859, when he was appointed a judge of the Irish Bankruptcy Court and transferred to Dublin. On his departure from Cork, Judge Berwick gave a generous gift of a fountain to the city: the Berwick Fountain on Grand Parade is still a well-loved landmark in Cork today. Berwick was one of the founders of the Stillorgan Convalescent Home, where a new wing was named after him in 1869. With Judge Berwick on the ill-fated train were his sister Elizabeth, her maid Jane Ingram and a nine-year old girl whom they had agreed to chaperone from London. They all died, and the girl, Louisa Symes from Rathdrum, Co. Wicklow, was the youngest victim. Other Irish victims included Revd Sir Nicholas and Lady Chinnery, who came from Flintfield, near Millstreet, Co. Cork, and William Owen, organist of St Bartholomew’s Church in Dublin.

The 33 victims all lie in Abergele churchyard under a monument inscribed ‘In the midst of life, we are in death’. These were the words used by Lord Farnham in the Anglo-Celt newspaper when he expressed gratitude to his tenants for their formal condolences on the tragic deaths of his brother and Lady Farnham in ‘circumstances which have not only sent a thrill of unprecedented awe and amazement throughout the whole community, but which remind us in tones of the most solemn warning that in the midst of life we are in death’.

Bryan MacMahon is the author of The Great Famine in Tralee and north Kerry (Mercier Press, 2017).

FURTHER READING

R. Hume, Death by chance: the Abergele train disaster, 1868 (Llanrwst, 2004).