Tartan gangs

Published in Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2017), Northern Ireland 1920 - present, Volume 25IN 1968 FUTURE RED HAND COMMANDO FRANKIE CURRY, A THIRTEEN-YEAR-OLD NEPHEW OF IMPRISONED UVF FIGUREHEAD GUSTY SPENCE, WOULD INADVERTENTLY CAUSE THE BIRTH OF A LOYALIST YOUTH SUBCULTURE THAT WOULD GREATLY INFLUENCE EVENTS DURING THE VIOLENT EARLY 1970S IN BELFAST.

By Gareth Mulvenna

Frankie Curry and some of his Rangers-supporting friends were in a Shankill street gang known as Shankill Young Team. Named in tribute to the violent Glasgow gangs of the day, they regularly travelled to matches at Ibrox with hundreds of other supporters from Ulster. It was during one of these trips that Curry is said to have shoplifted a tin box containing burberry-patterned scarves. Donning them in a local snooker hall, the gang was thereafter dubbed ‘Shankill Young Tartan’.

Several street gangs in Belfast

The Shankill Young Team was one of a number of gangs in Belfast during the late 1960s. The Nurks, a Catholic gang that drew members from the Newington and Carrick Hill areas, had an ongoing rivalry with the Yeti, a gang of loyalists from York Road and Tigers Bay. (Also on the Shankill was the Ant Hill Mob, whose comic name belied the extreme sectarian violence that would eventually be unleashed by one of its members, Lennie Murphy.) Frankie Curry and his contemporaries were to come of age as the 1960s turned into the 1970s and law and order fell apart completely in Northern Ireland.

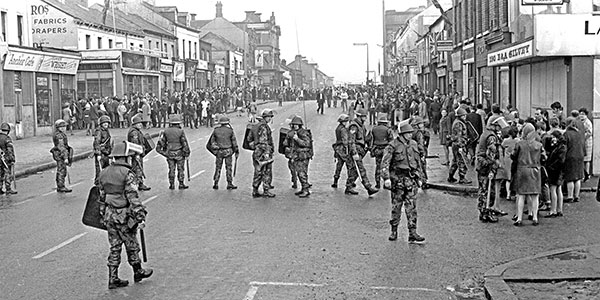

Above: Protestant Tartan youths on parade, June 1972. (Alamy)

Over the last weekend of June 1970, Provisional IRA gunmen killed six Protestant civilians in north and east Belfast during and after Orange parades. Ronnie McCullough, who had just turned eighteen, was one of the Orangemen on the Crumlin Road when marchers and their supporters were attacked. In the aftermath he and a small group of his friends descended on his mother’s house in the Oldpark area and debated what had occurred. McCullough remembers that the birth certificate of a then unnamed group, which would later become the Red Hand Commando, was verbally agreed:

‘In effect we agreed on two founding principles for this proposed organisation … we would fight to remain British, and we would not be forced into an all-Ireland republic … and secondly that we would fight to defend the Protestant people, or loyalist people—our communities—from republican aggression.’

The militant group was ill equipped for what loyalists increasingly felt would be an all-out civil war. The late ‘Plum’ Smith, another early member of the Red Hand, wrote in his autobiography that the organisation’s ‘first trawl of weapons looked like something from a WWI museum …’.

Above: British soldiers confront loyalists on the Shankill Road, following an outbreak of violence triggered by Protestant supporters of Linfield attacking the predominantly Catholic Unity Flats on their way home from a match on Saturday 26 September 1970. (Victor Patterson)

Backed by John McKeague, Shankill Defence Association

Despite his young age, Ronnie McCullough was already a well-known figure on the Shankill who had delivered Orange lectures for his mentor Billy Spence, brother of Gusty. McCullough and the cadre of young loyalists who had met in his mother’s house decided to approach John McKeague, leader of the Shankill Defence Association. Having been disowned by Ian Paisley and the Free Presbyterian Church, McKeague was smarting and thus was galvanised by the enthusiasm he encountered among the young loyalists. McCullough remembers:

‘Whenever it was put to John McKeague what the aims of this new group were, and what their objectives were, [he] fully endorsed them and encouraged them to link in with those people who were already members of the Shankill Defence Association and felt the same way. It ended up that numbers of Shankill Defence Association members became close to this new grouping, and in actual fact they all amalgamated and formed one grouping which was later to become the Red Hand Commando.’

Throughout 1970 and 1971 the Tartan look would become increasingly popular among young loyalists, many of whom were supporters of Linfield Football Club. As 1970 progressed, the recently built and predominantly Catholic Unity Flats housing estate at the foot of the Shankill became a focal point for altercations after Linfield games.

Across the city in east Belfast, loyalists had been involved in similar altercations with republicans from the small Short Strand enclave at the foot of the Albertbridge, Woodstock and Ravenhill roads. Memories were also still fresh of the fatal shootings of Protestants by republicans who were located in the grounds of St Matthew’s Catholic church in June 1970.

In early 1971 sixteen-year-old Robert Niblock was in a gang named Young Hatan, but as trouble grew the Young Hatan merged with other gangs and became the Woodstock Tartan. Whereas the Shankill Tartan now wore the red Royal Stewart pattern, the Woodstock gang opted for a white variant of the Stewart tartan. Niblock remembers that gang members wore the design

‘… one-yard-long … four inches [wide] and worn like a cravat; unless you tied it from your left wrist … right-handers anyway. This was usually the practice when confronting another gang. For the Crombies or suit coats, when we sometimes wore them, a small cutting of the same Tartan was left poking out of the top pocket.’

The Tartan subculture gained momentum in the wake of the Provisional IRA murder of three young Royal Highland Fusiliers on 10 March 1971. After this event the Tartan gangs proliferated and became a solid symbol of militant loyalist resistance.

‘Young hooligans’?

Despite the ongoing republican violence, the Tartan gangs were often involved in the kind of working-class conflict associated with youth gangs in other industrialised cities, most notably the defence of territory. In April 1971 the Belfast News Letter led with a headline declaring that ‘Shankill gang war is new threat to Belfast peace’. Describing an altercation between the Shankill Tartan and another gang, the Rats, an angry resident told the newspaper that the gangs were young hooligans:

‘Last week I saw members of the two gangs fighting in a vicious and cruel manner. They used belts and knuckle-dusters and I saw one young boy knocked to the ground and about three other youths started kicking him in the face. Just then a couple of men arrived on the scene and went to the boy’s aid. When they asked him who was responsible he refused to answer. From what I can gather they have a code of silence and you must not squeal.’

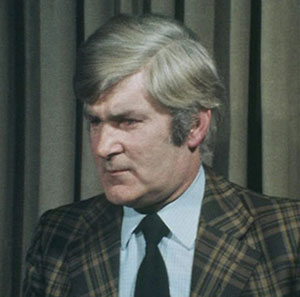

Above: John McKeague of the Shankill Defence Association—when approached by eighteen-year-old Ronnie McCullough and friends in 1970, he fully endorsed their activity. (BBC)

‘I wonder if it is absolutely correct to describe these people as young hooligans. Accompanying this parade was a large number of young men in blue denims … I am told that at a section of the parade … these young men numbering hundreds attempted to goosestep and behave in a disciplined military way. I presume they could be called true blues. These are militants on the Unionist side, and they accompanied this march for the express purpose of ensuring that if there was any trouble they would be able to go into action as a type of military force … there is more than young hooliganism involved in this.’

‘No-warning’ bomb

On 29 September—seven weeks after the introduction of internment—Linfield supporters thronged the public houses on the Shankill Road following a European Cup defeat to Standard Liège. At around 10.20pm a ‘no-warning’ bomb placed at the door of the Four Step Inn exploded, tearing the pub down. The first sectarian pub bombing of the Troubles had occurred and loyalist fears calcified.

Ronnie McCullough was among the Linfield supporters that evening; he had returned to his house, where he heard the explosion. Like many others, he hurried to the site of the bomb:

‘… the Four Step Inn … which I frequented with my friends, had been bombed … it was a traumatic occasion. I seen a woman with her foot hanging by a thread … I seen them carrying the injured and the two dead people out of the building.’

The impression left on McCullough was similar to that left on many other young loyalist men at the time:

‘[the bombing] again reinforced our view that violent republicanism, especially from the Ardoyne area, was totally intent on indiscriminate attacks, not only on British soldiers, as they had done with three Scottish soldiers … now they had no qualms on no-warning bombing against innocent Protestant civilians … it reinforced our view that there is now a need for young loyalists to form, to organise and find some means of defence and attack to repel any further attacks and to dissuade republicans; and to dissuade Catholics from giving support or succour to the republican bombers and gunmen in their midst.’

As these attitudes began increasingly to prevail, 1972 would prove to be a turning point in loyalist paramilitarism. Peter Taylor, who reported from Belfast at the time, recalls that the early loyalist assassinations in January, February and March 1972

‘… began slowly and spasmodically at first and became chillingly more frequent as day by day loyalists saw the security and political situation apparently getting worse … Most of the killings were purely sectarian and at this stage seldom claimed directly by the organisations involved.’

Ambiguity about organisational responsibility

This ambiguity about organisational responsibility led to a number of rumours about who was perpetrating the loyalist violence. Inevitably the Tartans were never far from people’s lips when gossip about the latest assassination spread. This was particularly evident in the case of the killing of Patrick McCrory, a young man from Ravenhill Avenue in south-east Belfast, in March 1972. In the aftermath of McCrory’s murder, his father spoke to the Irish News, stating that

‘I have no doubt … that the people who killed my son were members of a Tartan gang. Nine months ago my son was waiting for his girlfriend in Hope Street when he was attacked and beaten by a gang of youths.’

McCrory’s father also referred to a more recent event in which his son had been beaten by the local Tartans: ‘Three weeks ago he came into the house in a very distraught state and told me that he had been attacked again, by a gang on the Cregagh Road a short distance from his home’.

In May 1972 the BBC dispatched Max Hastings to east Belfast to record Twenty-Four Hours; his brief was to find out more about the Tartan gangs. In a scene filmed in a local youth club near the Woodstock and Ravenhill roads, the young tartan-scarf-wearing, denim-clad lads were seen playing pool and dancing with girls. In any other UK city this would have appeared normal. In Belfast, just over a month after Stormont had been prorogued, the Woodstock Tartans were expected to do more than just follow youthful pursuits.

On the streets surrounding the club Hastings discovered overwhelming support among adults for the Tartan gangs. One woman stated that ‘These are our boys of tomorrow’, while another declared that ‘The Tartans are only the start of it. It’ll come to the whole Protestant population will have to come out and do what they’re doing to get anything in the country.’

Sworn into the Red Hand Commando

About ten weeks later, during that hot and horrific summer of 1972, a group of the young Woodstock Tartans would join the Red Hand Commando, having turned down approaches from the UDA and Tara. Robert Niblock, a young Woodstock Tartan member who later wrote a play about his experiences of this period, recalls:

‘… we had approaches from the UVF officially, approaches from the Red Hand, from Tara … two older guys who came and played tape recordings and gave us a presentation … the Orange Volunteers … brought a couple of us for weapons training as well’.

As these approaches were being made, the political and security context had deteriorated to such an extent that the Revd John Stewart, a Methodist minister from Woodvale in the upper Shankill area, was compelled to describe the emerging situation as the ‘Protestant majority’s high noon’. Stewart also stated ‘that from the Christian point of view to speak of restraint sounds hollow and unrealistic to those who live in the streets of uncertainty, disappointment and discontent’.

By July a bellicose anti-authoritarian mood prevailed in the terraced streets of loyalist Belfast. Vanguard and Ulster flags took the place of the Union Jack, with the Sunday News noting that many streets in east Belfast saw a ‘dramatic splah [sic] of colour’ with ‘“ceilings” of red, white and blue bunting’.

Above: A Vanguard rally in Ormeau Park, 18 March 1972. Note the ‘Tartan look’. (Billy Beggs)

It was against this colourful and dramatic backdrop that on the evening of Thursday 20 July some of the original members of the Woodstock Tartan made their involvement in loyalist paramilitarism official by agreeing to be sworn into the Red Hand Commando. As a group, the young men usually met on a Thursday evening in the Raven Bar. This Thursday, the evening before Bloody Friday, would be the final step across the Rubicon. Robert Niblock describes the scene that evening:

‘There was a lounge up the stairs with a sort of raised area where they played darts … They had set up the table with a Union Jack, and a bible and a Luger gun.’

The senior members of the group who had arranged the table then went downstairs, reappearing after fifteen minutes with two other young men, Ronnie McCullough—aged just twenty—and another Shankill Red Hand Commando, Sammy Neill. ‘The two guys, I’d known them to see … they put on pilot jackets and berets and swore us in.’

The transition from young citizen to volunteer through the Tartan gang culture was complete. Niblock, then seventeen, was more than cognisant of the solemnity of the oath that he and his friends had taken:

‘You felt as if you’d achieved something; certainly it was a dividing line—you were going from something where maybe you could have been f—ing about, to … this is serious now. Certain ground rules were laid down. You were told here’s why you’re joining the organisation, here’s the reasons you should be joining the organisation, and here’s what’s expected of you … it was formal then, whereas there was none of that in the Tartan. There was a line we knew we’d crossed, and things were going to take a more serious turn.’

Gareth Mulvenna is a member of the Donegall Pass Social History Group and is the author of Tartan gangs and paramilitaries—the Loyalist backlash (Liverpool University Press, 2016).

FURTHER READING

D. Boulton, The UVF 1966–73: an anatomy of loyalist rebellion (Dublin, 1973).

R. Garland, Gusty Spence (Belfast, 2001).

W. ‘Plum’ Smith, Inside man: loyalists of Long Kesh (Newtownards, 2014).

P. Taylor, Loyalists (Bloomsbury, 1999).