‘Sworn to no master’: Doctor Bernard Connor (1666–98)

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Issue 1 (Jan/Feb 2008), News, Volume 16Born in Kerry, Bernard Connor received his early education in Ardfert and went to university in France, first in Montpelier and then Rheims, graduating there as a doctor of physic in 1693. He travelled widely in his short career. After a brief period practising medicine in Paris, he set out to accompany the sons of the chancellor of Poland back to their homeland. This journey began in late 1693 and took him through the cities of Europe, where he met and treated several of the English aristocracy. His reputation as a physician grew. He also visited the leading medical centres of the Continent, consulting with other great minds. On arrival in Poland in early 1694, he was invited by King Jan III Sobieski to become his personal physician.

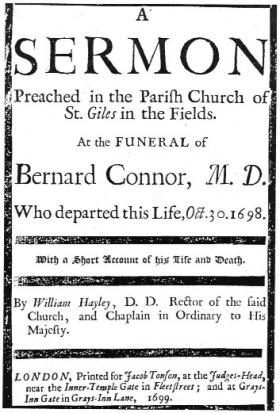

Frontispiece of the published sermon delivered by Rector William Hayley of St Giles in the Fields at Connor’s funeral on 30 October 1698. Connor was buried in the crypt. (Royal College of Physicians of Ireland)

By then the great warrior-king was in decline, with considerable health problems and in need of a good doctor. Connor’s finest hour was when he diagnosed that the king’s sister had an incurable abscess of the liver. Ten of the leading physicians of Warsaw disagreed, and were aghast at the young Irishman’s audacity in challenging them. The woman died within the month, and an autopsy confirmed Connor’s diagnosis.

Connor soon found a convenient way to leave Poland. In late 1694 he took on the responsibility of accompanying the

king’s only daughter to Brussels to marry the Elector of Bavaria. During that long winter journey, Connor carefully recorded information from his companions about the history and customs of Poland. This research formed the basis for his 700-page History of Poland, published after his death.

Connor crossed to England in the spring of 1695 and took up residence in Bow Street, Covent Garden. His reputation preceded him and he began to move in elevated intellectual circles. He was invited to lecture on medicine and natural philosophy in the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. He published several books, and was allowed the privilege of conducting his experiments in the library of the archbishop of Canterbury. He was elected a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and the Royal Society, and became a member of the prestigious French Academy. All his lectures and medical treatises were written in Latin.

Connor was the first to identify and describe the medical condition ankylosing spondylitis, whereby the bones of the spine fuse. This was accomplished very early in his professional life, in 1693. His dedication to anatomy and to dissection set him apart from his peers. He had a firm belief in the value of research, experimentation and the scientific method:

‘It is plain to me . . . that the causes of diseases, and the true use of applications to cure them, can be rendered very intelligible; so that the vulgar axiom that “there’s no certainty in physick”, will be found most erroneous’.

He had great self-belief and a willingness to reject the established wisdom of the times:

‘Since therefore experience and reason are our only guides, no body is to take it amiss if I censure such as wrote before me, with as much justice as they did their predecessors: for I am sworn to no master’.

The opening page of the second volume of Connor’s History of Poland, published in London shortly after his death in 1698. (Royal College of Physicians of Ireland)

An admiring biographer wrote that Connor

‘. . . startled the scientific orthodoxy of his time almost as thoroughly as did Charles Darwin, and the theological stability of Saxondom almost as efficiently as did John Henry Newman’.

In a religious age, Connor’s advanced views sometimes got him into trouble. When others believed that the moment of death was the moment when the soul left the body, Connor once shocked an audience in Poland by proposing that death occurred when the heart stopped beating. In one of his books, Evangelium Medici, he set out to show that there could be a natural explanation for the miracles of the Gospels, and for this he was accused of heresy. The outcry against him was a chastening experience, and he wrote: ‘I am resolved not to meddle any more with matters of this kind, but to apply myself entirely to the practice of physick’.

In 1698 Bernard Connor contracted a fever and died on 30 October, only days after symptoms appeared. Revd William Hayley gave Connor communion according to the Church of England rite, after rigorously testing his religious convictions. Then an Irish priest arrived at Connor’s bedside, claiming to be a friend and a relative. They conversed in Irish, and Connor received absolution and the last sacrament from this priest. Despite this, Hayley still considered him a true Anglican, and Connor was buried in the crypt of St Giles in the Fields in central London, with Hayley preaching at the service.

Bernard Connor’s History of Poland is now regarded as a very useful source for the early history of that nation, the first publication of its kind in English. His friend John Savage did the final editing, and it was published in 1698. One of the tales recorded by Connor was that of a Lithuanian boy who had been reared in the wild by a bear. Connor himself saw the boy, and described his demeanour and the efforts to train him to walk on two legs rather than on all fours. This early account of a ‘feral child’ is regarded as an important contribution to that field of study.

The short career of Bernard Connor has been described as ‘a continuous triumphal progress’. He was a real Renaissance man of immense gifts, who challenged the orthodoxy of the age with a confidence which promised much for his future career. Many scholarly articles have been published in medical journals on Connor’s contribution to the early development of medicine, and in September 2006 the pharmaceutical company Abbott inaugurated the Dr Bernard Connor Bursary of e10,000 for innovation in rheumatology.

Bryan MacMahon is a historian of north Kerry.