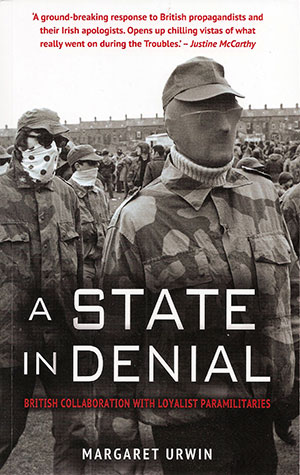

A state in denial: British collaboration with loyalist paramilitaries

Published in Book Reviews, Book Reviews, Issue 2 (March/April 2017), Reviews, Volume 25MARGARET URWIN

Mercier Press

€13.49

ISBN 9781781174623

Reviewed by: Raymond Murray

This is the third scholarly book in recent times that shows how successive British governments abandoned morality and law in dealing with conflict in Northern Ireland. Published in 2012, Ian Cobain’s Cruel Britannia: a secret history of torture reveals how the British government over the last 70 years has repeatedly and systematically resorted to torture, bent the law, told lies and made categorical denials. The author includes Northern Ireland in his research and, indeed, the case of the ‘Hooded Men’ of 1971, the torture of fourteen men in military barracks, is once again being brought before the European Court of Human Rights. After fifteen years of research, Anne Cadwallader published in 2013 her Lethal allies: British collusion in Ireland—a frightening portrayal of collusion. It has been described as an ‘ugly story dealing with the sectarian murder of non-combatants and the inexcusable failure of the British and Irish states to protect their citizens’. Commenting on her own book, Lethal allies, on the evening of the launch of Margaret Urwin’s A state in denial in the Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich Memorial Library and Archive on 3 November 2016, Anne Cadwallader said:

This is the third scholarly book in recent times that shows how successive British governments abandoned morality and law in dealing with conflict in Northern Ireland. Published in 2012, Ian Cobain’s Cruel Britannia: a secret history of torture reveals how the British government over the last 70 years has repeatedly and systematically resorted to torture, bent the law, told lies and made categorical denials. The author includes Northern Ireland in his research and, indeed, the case of the ‘Hooded Men’ of 1971, the torture of fourteen men in military barracks, is once again being brought before the European Court of Human Rights. After fifteen years of research, Anne Cadwallader published in 2013 her Lethal allies: British collusion in Ireland—a frightening portrayal of collusion. It has been described as an ‘ugly story dealing with the sectarian murder of non-combatants and the inexcusable failure of the British and Irish states to protect their citizens’. Commenting on her own book, Lethal allies, on the evening of the launch of Margaret Urwin’s A state in denial in the Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich Memorial Library and Archive on 3 November 2016, Anne Cadwallader said:

‘In over three years, not a single fact has been challenged—let alone the principal statement made—of wholesale and substantive collusion in 120 murders. Yet London still refuses to comment, admit, acknowledge, accept or apologise.’

The book was a great success, selling upwards of 20,000 copies. According to Cadwallader:

‘Since 23 October 2013 it has been debated in Leinster House and the House of Commons. We have been given two hearings at Congress DC and at a meeting of the Federal Parliament of Australia in Canberra.’

Now comes the third ground-breaking book, A state in denial: British collaboration with loyalist paramilitaries by Margaret Urwin. In the foreword Paul O’Connor, director of the Pat Finucane Centre, comments:

‘The declassified documents discussed within these pages paint an extraordinary picture. Where Lethal allies explored the extent of collusion during a specific time in a specific area, A state in denial peeps behind the doors of Whitehall and Stormont in the 1970s and 1980s. The picture that emerges is one of toleration and even de facto encouragement of loyalist paramilitaries.’

The content of Margaret Urwin’s book is summarised on the cover:

‘Secret Army units, mass sectarian screening, propaganda “dirty tricks”, the arming of sectarian killers and a point-blank refusal to outlaw the largest loyalist killer gang in Northern Ireland, all point to the incontrovertible fact that collaboration did exist between successive British governments and loyalist paramilitaries. Tactics such as curfew and internment were imposed almost exclusively on the nationalist population of Northern Ireland.

Based on research by the Pat Finucane Centre and Justice for the Forgotten, and using official British and Irish declassified documents from the 1970s and early 1980s, this book explores the tangled web of relationships between British government ministers, senior civil servants, leading police and military officers, and UDA and UVF paramilitaries. The documents provide evidence of more than a decade of official toleration, and at times encouragement, of loyalist paramilitaries, leading to horrifying results and prolonging the conflict in Northern Ireland. Yet the authorities in London continue to deny such links. Britain truly is a state in denial.’

After the Dublin and Monaghan bombings, Margaret Urwin and companions worked hard to uncover the truth about who was responsible, putting pressure on both the British and Irish governments. She worked with Justice for the Forgotten, the organisation representing the families and survivors of the Dublin and Monaghan bombings, since 1993, and for more than a decade with the families of victims of other cross-Border bombings. Justice for the Forgotten affiliated with the Pat Finucane Centre in December 2010.

This is a thoroughly researched book, not only utilising previous research, as the bibliography indicates, but also especially analysing the declassified documents from the 1970s and 1980s and the evidence of various witnesses. It captures the atmosphere of each year and phase of the gruesome conflict. What does she offer in her book?

‘The purpose of this book is to explore the tangled web of relationships between British ministers, senior civil servants and senior police and loyalist paramilitaries in both the UDA and the UVF. By using the lens of official British and Irish declassified documents from the 1970s and early 1980s, it will also put into context the loyalist intimidation and sectarian campaigns that occurred in Northern Ireland throughout this period.’

One wonders what other documents lie hidden in state archives. Will this book encourage others to bring pressure on the British government to reveal them?

Year after year, families who suffered state violence were represented by skilled legal teams and organisations like the Pat Finucane Centre and Relatives for Justice, the Committee for the Administration of Justice, British–Irish Rights Watch and Amnesty International, who pressurised the British government to disclose information regarding state violence. Legal teams and families of those killed, injured and bereaved have pursued truth and justice. We remember that in May 2001 the European Court of Human Rights ruled that human rights were violated in the cases of eleven people killed by the security forces in Northern Ireland. The Stalker/Sampson Report and the three Stevens Reports have essentially been ignored or thwarted. Sir John Stevens defined collusion as ‘the failure to keep records, the absence of accountability, withholding of intelligence and evidence and the involvement of intelligence agents in murder’. His 3,000-page full report contains names, accusations and recommendations, but only a very short summary has been published. It remains a secret and has so far been suppressed by the British government. The Stevens team claimed to have interviewed 15,000 people, catalogued 4,000 exhibits, taken 5,640 statements and seized 6,000 documents. None of the details are available for public scrutiny. There were three reports. Only twenty pages of the third report were published. Judge Cory’s reports followed, but as an example of suppression of the truth the government failed miserably in not setting up a public inquiry into the Pat Finucane case. Judge Cory in his report criticised the RUC Special Branch for paying little attention to loyalist paramilitaries. He said that ‘the documents indicate that in some instances Special Branch failed to take any steps to prevent actual or planned attacks on persons targeted by Loyalist terrorist groups’.

The state has always played for time, hoping that pressures would ease, and it has denied complicity in the violence. It has defended the actions of the security forces. But a point must be made that the state authorities themselves must bear a responsibility for unlawful killings. One asks what subcommittees under government debated issues and gave the go-ahead for killings? There is never an acceptance from government that their own members were responsible for unlawful killings in the policies they pursued.

Who gave the British Army and the police permission to use the UDA as a third force? The UDA was responsible for many murders, and the government would have known that most UDA weapons came from the UDR, a regiment of the British Army. The UDA was kept legal until 1992, and of great interest is the final chapter on when blatant truth reached a public crisis point: it is called ‘RUC Raids on UDA Headquarters Embarrass the British Government’. The world knew that attributing their murders to a false paramilitary force called the UFF (Ulster Freedom Fighters) was a sham. The UDA murders, the British Army murders, and the involvement of some UDR and RUC members in murders point, as this book testifies in its deep research, to the collaboration of successive British governments with loyalists and a one-sided military campaign against republicans, and also in a wider degree against the Catholic population.

A few remarks regarding British governmental control come to my mind from my book The SAS in Ireland (2004). So much still rings true today, as brought out in the three books highlighted in this review:

‘The allegations over years of British state terrorism including actions of the SAS were well founded and those who made allegations of collusion vindicated by the Stevens and Cory Reports. British governments and security chiefs must be made judicially responsible for extra-judicial killings if it is found in public inquiries that they were complicit in such crimes. Human rights standards were needed most at a time of conflict and that is where successive British governments failed. It is important now to promote public confidence in security services. This will only happen when the British state opens up the sources it has locked up over the years of a long-running conflict. The revelation of the truth would in fact hasten the pace of healing and reconciliation and brighten the vision of peace in a new Ireland. Justice must be seen to be done for the sake of law, morality and democracy.’

After years of campaigning, corruption and gross injustice were incontrovertibly exposed in the cases of the Guildford Four and the Birmingham Six. Margaret Urwin’s book adds to our knowledge of the vast undercover operation of intelligence-gathering, surveillance, harassment and bloody action. So often injustice was a consequence. The state allowed its covert army to operate with immunity. When their operations were probed, it was prepared to go to incredible lengths to defend them.

I will end with a quote from the book’s conclusion:

‘The documents quoted throughout this book raise disturbing questions. Did the refusal by the British government over two decades to proscribe the UDA constitute a continuing breach of Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights? The Right to Life and the duty imposed on states to protect this right is a fundamental principle in domestic, European and international law. The UK government may have been guilty of a flagrant breach by formulating policies that put its citizens at risk and thus constituted misfeasance in public office on a hitherto unimaginable scale.’

I congratulate the author on her painstaking study of released documents and on her balanced judgement. It is fitting also to congratulate the Pat Finucane Centre for its cooperation with Margaret Urwin and also to thank Mercier Press for a splendid publication.

Msgr Raymond Murray is joint author (with Fr Denis Faul) of The Hooded Men: British torture in Ireland, August, October 1971 (1974; Wordwell Books, 2016).