A St John Ambulance man in 1916: Robert Leask’s diary

Published in Features, Issue 3 (May/June 2016), Revolutionary Period 1912-23, Volume 24A CANDID, METICULOUS AND OCCASIONALLY HUMOROUS ACCOUNT OF EASTER WEEK

By Anne Carey

Above: Robert Leask in later life. In 1916 the then 37-year-old Presbyterian insurance manager was a sergeant in the St John Ambulance Brigade in active service at Guinness’s brewery.

Robert was a 37-year-old Presbyterian insurance manager living with his young family in the comfortable suburb of Rathmines. Like many of the citizens of Dublin, he was surprised and alarmed by the Rising, but as a sergeant in the St John Ambulance Brigade in active service at Guinness’s brewery he provided aid to all, irrespective of their allegiances.

‘Ned Carson is the one to blame’

Leask’s account begins on Easter Monday, 24 April, ‘a beautiful morning, working in the workshop and garden; began to hear reports of Sinn Féin rising in Dublin’. Rumours quickly circulated that there had been ‘a German landing in Kerry, and the streets of Cork running with blood’, with Leask himself surmising ‘that these people would not be such fools as to put their heads in a halter, and that consequently there must be a general rising and probably an attempt at the invasion of England by Germany’. Later that evening he had a conversation with a tram driver who told him of civilians and tram men killed: ‘I’ll tell you what sir, it’s Ned [Edward] Carson is the one to blame for all this; it was he started arming the people’. On the following day Leask went into town via Portobello Bridge, where he saw ‘Davys public house riddled with bullets’. In town he saw

‘… three civilians, dead, were lying on the east side of the Green that morning, and in spite of all this people were walking up and down past the College of Surgeons, gaping and generally looking for trouble … My nephew “Bobs” took a run around the Green on his bicycle, and when near the Shelbourne saw two soldiers emerge from Kildare Street or Merrion Row and fall from a volley from the Green—no one to tend them—women running away shrieking.’

Nervous sentry

Leask was one of 180 members of the ambulance division of the St John Ambulance Brigade in service during Easter Week. In advance of his reporting for duty to Portobello Barracks at 8am on Wednesday 26 April, he discussed with his commanding officer ‘the possibilities of getting snuffed out, and what would become of the Missus and chicks—felt that Lil [his wife] was very anxious but subsequently felt quite comfortable when I wormed it out of her that she would not like me to hang back’. He witnessed at first hand the inexperience of the hastily gathered forces the next morning, when he was faced with a nervous sentry at Portobello Barracks who, in spite of seeing his St John Ambulance Brigade uniform, levelled his gun at him as he approached:

‘I felt sure he would pull the trigger by mistake and incidentally by accident hit me whom he aimed at, so wished again for the 50th time that I have more life insurance, and that with some office other than my own; however, the beggar looked away with such a scared face, and whispered to an officer with the guard a few yards away “What’ll I say?”.’

Leask was transported to Guinness’s brewery, where

‘… well about mid-day our local noise began, there had been constant firing city-wards, machine guns, rifles, bombs, and I fancy big guns, but the wind was in the other direction; however, our local sports began with bombing the Mendicity Building [held by the young Seán Heuston], and crashes of rifle fire from overhead and all corners, evidently the soldiers potted at everything that moved once the bombing started, the noise of these bombs continued and they would nearly lift you off your feet.’

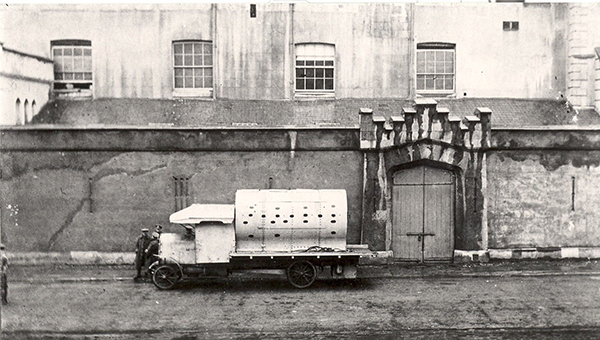

There were a number of calls on Leask’s ambulance unit on Wednesday and Thursday, including a British soldier with abdominal injuries whom they carried away to the sounds of ‘the keening of the female population in that neighbourhood “Oh the poor fellow”—“Oh the lovely soldier”, etc.’ A second call was for ‘a Sinn Féiner with half his head knocked off lying in a pool of gore’, and the third was for a civilian. Leask was relieved of duty on Thursday and returned to Guinness’s brewery again on Friday, where ‘… we were saluted by all with cheers and handkerchief waving as we dashed along on one of Guinness’s big motor lorries’. He also got to witness one of the curiosities of the Rising, ‘an improvised armour car, one of the brewery motor lorries with an old engine boiler fixed up’.

One of the worst incidents of military inexperience

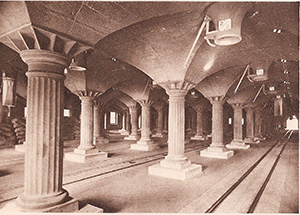

In the early hours of Saturday morning Leask witnessed the aftermath of what has been described as one of the worst incidents of military inexperience in the campaign. It involved the execution of a British army officer and a civilian by order of Company Quartermaster Robert Flood, with two further casualties shortly afterwards. Leask had been in conversation with QM Flood earlier that day, ‘a very interesting young fellow in charge of the section of the [Royal Dublin Fusiliers]; he seemed rather depressed with it all and wished he was back in India’. According to Leask, ‘at dusk there was a great air of mystery afloat’ and a section of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers was sent to a malt-house in Robert Street overlooking Marrowbone Lane, where a Sinn Féin attack was expected. At 11pm Lieutenant Algernon Lucas of the 2nd King Edward Horse Regiment, a man unknown to Flood, took command of the darkened malt-house. The inexplicable arrival of a brewery official, Mr W.J. Rice, aroused Flood’s suspicions, particularly when he thought he saw a look of recognition pass between Mr Rice and Lieutenant Lucas in the dim light of a single flashlamp. Flood initially placed both men under arrest but made the decision to execute them once it seemed like a Sinn Féin attack had begun. Acceding to Lucas’s request to be allowed to say a final prayer, Flood asked him why he was crying and he said it was for his wife and child. About half an hour after their execution Lieutenant Basil Henry Worswick, also of the 2nd King Edward Horse Regiment, came into the malt-house with Mr C.E. Dockeray, another brewery official, to ascertain what had happened to Mr Rice. Lieutenant Worswick lunged at Flood, accusing him of being a Sinn Féiner. Flood’s men shot both Lieutenant Worswick and Mr Dockerey dead during this confrontation. When the incidents were reported, Leask and his colleagues were dispatched to the casualties on the second and third floors of the malt-house. ‘Just as dawn was breaking a message reached us that there were some prisoners and wounded men in the malt house and to bring three stretchers—all bustle in a moment and we all move in the direction of the malt house.’

Above: Leask witnessed one of the curiosities of the Rising, ‘an improvised armour car, one of the brewery motor lorries with an old engine boiler fixed up’.

On the second floor of the malt house they found the bodies of Lieutenant Worswick and Mr Dockeray:

‘On the floor just in front of us lying on his back was a civilian apparently lifeless with staring eyes and a little blood at the corner of his mouth and his hands lying palm upwards, his hat off and looking generally gruesome; about three yards from this an officer in a horribly twisted up position, his face also staring and white with large beads of sweat all over his forehead … Now it was horrible, on examining these two men both had been shot clean through the heart and we found them dead but could not understand how they were shot where we found them. … We then went up to the next floor where we found two more, a Lieut Lucas of K.E.H. [King Edward Horse] on his back right at a window in which there were bullet holes and just though he had been looking out, and across this body also on his back lay Mr Rice another of the brewery men, and both these poor chaps had also been shot through the heart and were quite dead. Having regard to all the circumstances it was decided to leave them till the military people could investigate the matter, for already there were all sorts of tales developing, and sometime afterwards (I mean a month or so) [12 June 1916, at Richmond Barracks] the whole story became public through a court-martial of Q.M.S. Flood [where he was found not guilty], but in spite of this there appears to be considerable mystery surrounding the tragedy; the same will live in my memory forever, and though it was perhaps one of the least gory I had to look on it certainly affected me more than any other.’

Above: The exterior and interior of the Robert Street malt-house overlooking Marrowbone Lane, where Leask witnessed the aftermath of one of the worst incidents of military inexperience in the campaign. In the darkened malt-house in the early hours of Saturday 29 April, two brewery officials and two British officers were shot or executed by Royal Dublin Fusiliers Company Quartermaster Robert Flood and his men. (St James’s Gate Brewery, history and guide (1931))

As Leask emerged from this disturbing scene, he had an elevated view of the city away to the north-east:

‘… this Saturday morning the city appeared to be in flames, the area of the fire seemed to be enormous, and I sometimes think since that the conflagration must have merged into the sunrise, and my just-then heated imagination, though on going into the city the following Monday and seeing the destruction in Sackville Street alone, I came to the conclusion that it was all burning at the same time, the conflagration must have been immense.’

Leask’s curiosity as to the state of the town following the Rising led him to obtain a pass on Monday 1 May:

‘My brassard proved most useful and the police permitted me to go wherever I liked, which included a walk through the GPO and a hot walk it was for the fallen debris was still very hot; outwardly and at a distance there did not appear much wrong as it was a massive building but inside simply a roofless ruin.’

Certificate of Honour

Leask was one of 47 ambulance personnel who received a Certificate of Honour ‘for services rendered at grave personal risk as a memento of the rebellion’. His closing words on the 1916 Rising were: ‘I do hope it will be the last though it was almost enjoyable while it lasted’. In an interesting footnote, Leask’s brother Harold played an important role in the reconstruction of the GPO and the Four Courts between 1924 and 1932, when he was part of a small design team that oversaw the works.

Anne Carey is a freelance archaeologist and built heritage specialist based in Galway.

FURTHER READING

D. Kiberd, 1916 Easter Rebellion Handbook (Dublin, 1998).

F. McGarry, The Rising. Ireland: Easter 1916 (Oxford, 2010).

The author is grateful to Graeme Donald, grandson of Robert Leask, for bringing his grandfather’s diary to her attention, and to the Donald and Leask families for generously allowing this article to be published.