Shorthand for Protestants: sectarian advertising in the Irish Times

Published in 20th Century Social Perspectives, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, General, Issue 5 (Sep/Oct 2009), Volume 17

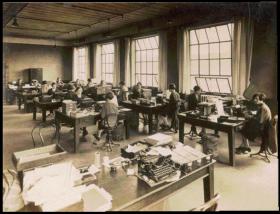

A typical typing pool in the 1930s. In Dublin in January 1960 Miss Elizabeth Synnott’s employment agency advertised in the Irish Times for ‘Protestant shorthand typists’. (Mary Evans Picture Library/Alamy)

In 1960 newly elected President John F. Kennedy was worried about an imaginary US–USSR nuclear ‘missile gap’. In Dublin Miss Elizabeth Synnott’s employment agency was worried by a ‘Protestant gap’. In early January 1960 in the Irish Times she advertised that ‘Protestant shorthand typists’ were ‘urgently wanted’. Later that month, ‘a Protestant shorthand typist (senior)’ was ‘available’, though in early February they were again required, either full- or part-time. In July, however, a Protestant with ‘excellent testimonials’ was offered to firms operating religious segregation at quite junior levels. And so it continued throughout the heady 1960s. Miss Synnott, who provided ‘a better selection’ (Dec. ’69), and the Irish Times alternately enticed or proffered ‘educated’, ‘experienced’ or ‘inexperienced’ Protestant office staff. In July 1970 Synnott’s still sought Protestants, long after the missile gap had vanished and during a period when the Irish Times was reporting civil rights movements in the US and in Ireland.

Protestants tended to be more managerial than proletarian

The 1953 examples are from the Irish Independent, where Protestant and ‘RC’ advertisers vied for space. In the Irish Times mostly Protestants were ‘preferred’. As they constituted less than 4% of the southern population, this indicates extensive sectarian recruitment. It also indicates social class diversity, with working-class Protestants advertising their existence and occupations. The Protestant population tended to be more managerial than proletarian, however, accounting for one third of directors and managers but only 652 of 48,000 labourers and unskilled workers in 1961 (Jack White, Minority report, 1975).

In his Protestants in a Catholic state: Ireland’s privileged minority (1983), Kurt Bowen reported that in 1955 80% of Protestants worked primarily with other Protestants and 90% worked first for a Protestant firm. The higher up one went within the managerial hierarchy, the more Protestant exclusivity was encountered. This included the Irish Times, where Jean Dunne (née Martin), the first Catholic employed in her grade in the 1960s, reported to me that the paper advertised for Protestant-only clerical/administrative staff. The un-suited printers were mainly Catholic, though.

Bowen outlined how Protestant preferment worked in the Irish Republic. Protestants and Catholics were educated separately. Protestant firms seeking staff wrote to Protestant schools and were also able to ‘identify Catholic applicants by their schooling’. These they put ‘aside’. Ads also appeared stating, for example, ‘Junior copy typist (Protestant) required by large city firm, age 16–21. Apply stating where educated’ (Jan. ’69). In November 1958 chartered accountants required a Protestant qualified assistant. In August 1973, possibly with the same object in mind, accountants wanted a ‘young man’ to supply ‘details of school attended’. If anyone got a raw deal it was women required to resign on marriage from the civil service and the banks. Four-and-a-half per cent of senior civil servants were Protestant in 1961, while senior banking positions had a 25% quotient in 1972.

In his (now sadly out of print) study, Bowen cited White on ‘a small number’ of such ads in the Irish Times ‘during the 1920s’. White reported three from 1927. In fact, sectarian advertising featured in every decade up to the 1980s and appears to have aroused little, if any, ‘Catholic hostility’. It was out in the open, in the lower-circulation Times and the circulation-leading Irish Independent, then a newspaper with a conservative Catholic profile.

Segregation

Protestant self-segregation suited Roman Catholic archbishop of Dublin John Charles McQuaid, who thought that there should be little, if any, contact from that direction. (National Gallery of Ireland)

It appears, on the basis of advertising, that southern Irish Protestants entered the world in a Protestant maternity hospital, attended by Protestant midwives, nurses and doctors and fed by Protestant cooks, went to a Protestant school, were fed by more Protestants and had wounds tended by a Protestant matron. Games played by Catholics were avoided, apart from soccer, where a Church of Ireland league maintained exclusivity. There were Protestant scouts and guides plus the Boys’ Brigade. At the appropriate time, Protestant employers were at hand, serviced by a Church of Ireland employment agency after 1925, and in 1944 the Dawson Employment Bureau ‘for employers and unemployed members of the Church of Ireland’, according to the Church of Ireland Gazette.

Social life was further facilitated by the YW- or YMCA and the parish dance, from which Catholics were excluded. Where interaction was required it too could be restricted. In September 1972 the ‘Badminton City Club (Protestant)’ advertised ‘vacancies’. Around the house, ‘Protestant man will do all your painting, papering and carpentry’ (Feb ’61), while the garden could be tended by ‘gardener, experienced, C of I’, also presumably a man (July ’63). Food could be purchased from a ‘general grocery’ that required a ‘reliable girl assistant (Protestant)’ (March ’61). Other household goods could be obtained from a ‘large departmental drapery’ that advertised for ‘two girls and two boys of school leaving age (Protestants)’ (April ’61). If in need of rented accommodation, an Irish Times scan would reveal ‘accommodation offered, Protestant business lady’, or ‘Protestant business gentleman offered partial board’ (both Sept. ’68). A ‘gentleman (C. of I.)’ advertised his requirement for ‘comfortable lodgings with breakfast and supper’ (Dec. ’64). If ill-health should befall, more Protestant nurses, doctors, cooks and other care workers were at hand, before days were concluded in a Protestant church and final resting place (‘First class plot, St Nessan’s Protestant section, Deans Grange, unoccupied [March ’70]). In such circumstances, very little, if any, contact with the other 95% might easily and agreeably, according to temperament, be contrived. It also suited those, such as the Roman Catholic archbishop of Dublin, John Charles McQuaid, who thought that there should be little, if any, contact from that direction.

Ne temere

One reason advanced for sealing off the Protestant population was the Catholic Church’s ne temere decree, requiring a Protestant spouse in a ‘mixed marriage’ to raise children as Catholics. ‘Losing’ Protestants in this way diminished the community’s capacity to reproduce. Owing to late age of marriage, age profile and emigration, Protestant numbers declined slowly until the 1960s. Nevertheless, such is human frailty, or the capacity of individuals to defy arbitrary standards, that illicit contact did take place. An unmarried pregnant Protestant woman might end up in theBethany Home, ‘the major facility for Protestant women in need of institutional care’, according to Bowen. The then Church of Ireland archbishop of Dublin declared it a ‘door of hope’ for ‘fallen’ women when it opened in 1922. Also involved was Revd T. C. Hammond, a leading Dublin opponent of Home Rule in 1912, a member of the Orange Order and the somewhat fundamentalist Anti-Ritualistic Society. In June 1957 the home advertised for an ‘evangelical missionary-minded nurse’ in the Irish Times. Annual meetings and ‘prayer days’ were presided over by Protestant clerics and duly advertised and reported in the Irish Times. In 1964 the paper commented that the home catered for ‘those in need of moral welfare and rehabilitation’.

‘Needy Protestants’

Northern Premier Terence O’Neill—his ‘advertisement for a Protestant housemaid . . . in a Belfast newspaper’ in 1964 was criticised in the Irish Times in 1972. Had he advertised anonymously in the Irish Times, as most did, this particular faux pas might have gone unnoticed. (Victor Patterson)

Somewhat Dickensian advertising reflected poverty and servility. In August 1941 the Irish Independent contained: ‘Wanted, orphan girl, 16–17, to help with light housework, treated as one of the family, Protestant preferred’. In January 1960 the Irish Times carried the following, twice:

‘Thoroughly domesticated woman (or orphan girl would suit). Protestant, to take charge of modern home . . . must be good at cooking or laundry. Good home for orphan girl with chance of learning business.’

Protestant poverty was apparent in the March 1968 bequest of Elizabeth Gertrude Barrett, ‘nursing home proprietress and spinster’, who left small parts of her estate to, amongst others, the Incorporated Association for the Relief of Distressed Protestants, the Irish Distressed Ladies Fund, Mrs Smyly’s Homes and Schools for Necessitous Children, and Miss Carr’s Homes. She left her premises to the Cheshire Foundation for the purpose of carrying on her profession. As archbishop of Dublin during the 1970s, Alan Buchanan regularly sought charity for ‘needy Protestants’.

The mechanisms adopted by the Church of Ireland, the largest Protestant denomination, preserved relative privilege, given what Bowen termed a ‘superior class position’. They were also in tune with the preservation of a conservative and patriarchal society. The Church of Ireland Gazette opposed Noel Browne’s Mother and Child scheme in 1951. A fear of socialised medicine was the basis of the Irish Medical Association’s and then RC Archbishop McQuaid’s opposition. As so often in the Irish state, a smokescreen of Catholicism prevented a view of the conservatism underneath.

While the church itself was somewhat imperial in outlook, members demonstrated degrees of idiosyncratic diversity. Bowen reported a tendency up to the mid-1960s to polemicise on the basis that the Church of Ireland was the indigenous Christian denomination and to emphasise Protestant fundamentalism rather than Anglican Catholicism. This was a means of ensuring separation from the Roman type. It had an unusual consequence for Alan Buchanan in the 1940s. John Graham, a member of St Mary’s Select Vestry on Belfast’s Crumlin Road, attempted to have Buchanan ejected for placing a symbol of ‘papish idolatry’—a portrait of Mary, the mother of Jesus—at the church entrance. Graham spoke regularly on his as the true Irish church and of Romanists as impostors. He first got wind of the offending items when his mother reported the ‘papish’ evidence while he was detained not far away in Crumlin Road Jail. He was one of a number of IRA Protestants who had specialised in intelligence work, known affectionately to a select few as the ‘prod squad’. Graham’s cellmate, IRA man Joe Cahill, reported Graham as ‘very convincing in his claims’.

Decline of separation

By the 1970s social separation declined. Bowen reported that during the 1960s and ’70s young Protestants endeavoured to smuggle Catholic acquaintances into Protestant-only functions and were themselves enticed by the bright lights of urban discos and dance bands. Like their Catholic counterparts, young Protestants were rebelling in a non-sectarian direction. More importantly, the steady erosion of the linchpin of Irish economic independence—protectionism—ended protection for Protestant-owned firms. After EEC entry many Protestant manufacturing, insurance or accountancy firms were bought out or expired. Industry became more reliant on external professional training. Hiring practice became more objective under the weight of equal pay laws, public opinion and, later, further anti-discrimination legislation.

Whereas in December 1962 there was a typical ad for ‘Matron (C. of I.)’ in an ‘elderly ladies home’, later such advertisements tended to state ‘Lady superintendent’ wanted in ‘home for elderly Protestant ladies’ (April ’78, Oct ‘80), thus rendering the applicant’s religion ambiguous. The old ways, recorded for posterity in the small ads rather than the news pages of the Irish Times, were dying out. Newspapers sometimes reflect the times better than they report them and offer insights for the social historian in overlooked places. In November 1972 the Irish Times’ Denis Coughlan was dismissive of those depicting former Northern Premier Terence O’Neill as ‘the darling of the Catholics’ and noted O’Neill’s ‘advertisement for a Protestant housemaid . . . in a Belfast newspaper’ in 1964. Had O’Neill advertised anonymously in Coughlan’s newspaper, as most did, this particular faux pas might have gone unnoticed, as apparently unnoticed as the fact that such ads existed in the first place. HI

Niall Meehan is Head of the Journalism and Media Faculty at Griffith College, Dublin.

Further reading:

K. Bowen, Protestants in a Catholic state: Ireland’s privileged minority (Dublin, 1983).

J. Martin, The Irish Times, past and present (Belfast, 2008).

M. O’Brien, The Irish Times: a history (Dublin, 2008).

J. White, Minority report: the Protestant community in the Irish Republic (Dublin, 1975).