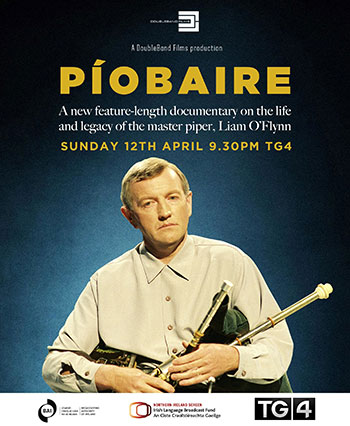

SEEN ON TV: Píopaire

Published in Issue 4 (July/August 2020), Reviews, Volume 28TG4

12 April 2020

DoubleBand Films

By Donal Fallon

In late 2002, music journalist Leagues O’Toole was presenting No Disco, a popular alternative music show on RTÉ television. The show provided a space for diverse acts over its years on air, but its most memorable television moment was a special edition dedicated to Planxty, a band founded in 1972. For a television show dedicated to indie music and emerging new sounds, it was a bold move on the part of the No Disco producer, Rory Cobbe, and RTÉ more broadly, but they allowed it to happen.

In late 2002, music journalist Leagues O’Toole was presenting No Disco, a popular alternative music show on RTÉ television. The show provided a space for diverse acts over its years on air, but its most memorable television moment was a special edition dedicated to Planxty, a band founded in 1972. For a television show dedicated to indie music and emerging new sounds, it was a bold move on the part of the No Disco producer, Rory Cobbe, and RTÉ more broadly, but they allowed it to happen.

In no small way, No Disco brought Planxty back to public consciousness. There was a glimmer of hope in it for future reunions, embodied by Christy Moore’s claim that ‘for me it hasn’t come to end … We may not have played for twenty years but it hasn’t come to an end. And it won’t for as long as we’re around.’ It would be impossible to imagine Planxty’s triumphant return in 2004 without No Disco.

The story of Planxty is at the heart of this documentary, but even the most dedicated of Planxty fans—among whom I would count myself—will learn much that is new from Píobaire. Indeed, in its first quarter one wonders whether the documentary would have been better entitled Píobairí—plural—given its masterful telling of the musical and social history of the uileann pipes more broadly. It is apparent early on that historical archive will be at the heart of the documentary, and we are treated to masterful performers like Seamus Ennis, Willie Clancy and Leo Rowsome, as the show introduces the audience to this strange and beautiful instrument. Without an understanding of the uileann pipes there could be no understanding of Liam Óg O’Flynn.

In a curious way, Liam Óg guides this documentary himself. In the absence of a narrator, historic recordings of Liam’s voice neatly join segments, on everything from childhood to later collaborations with Seamus Heaney. The assembled talking heads are staggering in diversity, from former president Mary McAleese to Liam’s fellow band members in Planxty, and from the aforementioned Leagues O’Toole to legendary traditional musicians from the early days of the piping scene in Dublin and Kildare.

Poor historical re-enactment, so often the downfall of Irish historical documentary, is absent. The only such shots we are treated to are of a vintage motorcycle journey, reflecting the childhood journey that Liam Óg took to Dublin with his father to learn the pipes from Leo Rowsome. The footage is used in such a way as to give the viewer the sense that we are on a journey throughout.

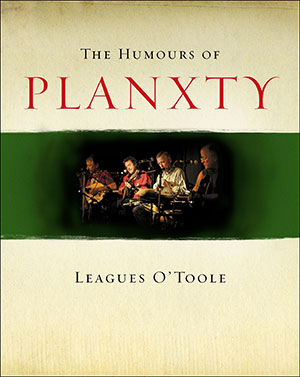

Above: Leagues O’Toole’s 2006 book, The Humours of Planxty, presents an image of a hard-partying band, but Liam Óg O’Flynn would usually travel separately and was far removed from the rock-and-roll lifestyle.

Planxty worked as a band primarily because it shouldn’t have—the fusion of, as Leagues O’Toole describes it here, the ancient and the modern. The documentary does a good job of demonstrating the feared musical contradictions and tensions, but it worked, as perfectly demonstrated by archive footage of the band. There is a reverence in how Planxty’s surviving members—in particular Christy Moore—discuss Liam and his music. They belonged to a world that was as much influenced by Woody Guthrie, Ewan MacColl and Phil Ochs as anything natively Irish, but Liam’s music was rooted entirely in Irish tradition. Liam, from a family of schoolteachers and a decidedly middle-class Kildare upbringing, always seemed somewhat out of sync with the lifestyle of his fellow band members. Andy Irvine’s diary from those days on the road, reprinted in Leagues O’Toole’s The Humours of Planxty (2006), presents an image of a hard-partying band (‘I retired to sleeping bag at 2.30am. The others were up till all hours and there’s been little respite from dope and energy so far’) but those tensions were not explored in much detail here. Liam would travel separately from the band generally, far removed from any rock-and-roll lifestyle.

Two filming locations stand out. Na Piopairí Uileann on Dublin’s Henrietta Street, a decaying Georgian building where many of the talking heads are interviewed, provided an unlikely home for Irish traditional music, but Na Piopairí Uileann were to the forefront of revitalising and saving one of Dublin’s most historic streets, along with the hard work of neighbours like the architect and republican Uinseann MacEoin, who saw a future—as well as a past—in Henrietta Street. With its high ceilings, beautiful fireplaces and stunning windows, Henrietta Street, as usual, proved its value as a filming location. The other was Liam’s home. As he was such a private man, it was a treat for viewers to get access to it. His widow, Jane, gave brilliant personal insights into her late husband, his love for horses (which she shares) and his enjoyment of sitting in his shed and getting lost in the poetry of Heaney. In listening to Jane, one realises just how private a person Liam was, never seeking personal recognition but always tipping his hat in the direction of the tradition. That Liam battled cancer for so long—more than fifteen years—will be news to many viewers too.

The footage of Liam’s funeral in 2018, his coffin being carried into a Kildare church, in a normal documentary about an individual would provide a natural conclusion point, for what story is left to tell? Just as Píopaire opened with a broader exploration of the uileann pipes and rooted them in an ancient tradition, the documentary ends brilliantly with a look to the future. Liam inherited the pipes of Seamus Ennis, and we learn in the closing moments of this documentary that a set of Liam’s pipes are now in the hands of Colm Broderick, a young musician from Carlow, 21 years of age. That sense of continuity is at the heart of the uileann pipes story.

Above: Planxty’s first album (1972).

Not unlike Planxty, there are things about this documentary that should not have worked but somehow did—the absence of a central narrator, the sheer number of contributors, the divergence from Liam’s story into broader history. Each bold editorial decision is rewarded. The production team, DoubleBand Films, have previously produced the acclaimed Seamus Heaney and the music of what happens, and it’s clear that divergence from the expected path is at the core of their work.

Today, it would appear that the uileann pipes are in a strong position. The 2019 Choice Music Award, in essence the Irish album of the year, was awarded to Lankum, a young Irish traditional music quartet (though, like Planxty, with diverse musical influences) who include an uileann piper in their ranks. Also nominated for the award was Junior Brother, a young Kerry musician who frequently features an uileann piper on stage with him. Such is Irish popular music in 2020.

Donal Fallon produces the ‘Three Castles Burning’ podcast (with a recent episode on Seamus Ennis and the uileann pipes in Dublin) and is co-editor of the ‘Come Here To Me’ blog.