Seá¡n South of Garryowen

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 1 (Jan/Feb 2007), Volume 15

Serious tension had developed within the leadership of the IRA as a result of the failure of its 1939 bombing campaign in Britain. When this was abandoned, its operations in Northern Ireland were scaled down for the duration of World War II. Both the Belfast and the Dublin governments introduced internment, and several hundred activists were put behind bars. A number were also killed in shoot-outs with the RUC, and in the South some were executed by the authorities or died on hunger strike, like Seán McCaughey from County Tyrone. When his death occurred in Portlaoise prison in May 1946 he had served four years in solitary confinement, two clothed only in a blanket. His funeral in Dublin produced an impressive turnout of mourners.

The immediate post-war period saw a significant revival of both political and militant republicanism, partly as a result of the release of internees but also because of the manner in which partition came to the forefront of Irish politics. The February 1948 Dáil elections were notable for the role played by the Anti-Partition League, which had been founded by Northern nationalists early in 1946. It sought countrywide support and asked voters ‘not to support any party that does not pledge itself to give active support to the Anti-Partition cause’. Taoiseach de Valera was willing to listen but insisted that his own party was best placed to achieve a 32-county republic.

Clann na Phoblachta

Fianna Fáil, however, lost the 1948 election, largely because of the impact of a new republican party, Clann na Phoblachta, led by Seán MacBride, a lawyer and former IRA chief-of-staff, who believed that the time had come to place partition on the agenda. It has been said that the IRA supported the Clann’s formation, and that it drew many of its foot soldiers from its rank-and-file. Disgruntled Fianna Fáil members were also sympathetic towards it, as were a number of left-wing radicals, who found the Labour Party much too conservative. After two by-election victories in 1947, the Clann became a threat to de Valera’s tenure. The election gave it ten seats and the right to ministerial office in the first inter-party government, along with Fine Gael, Labour and other smaller parties and independents.

MacBride, as minister for external affairs, was able to persuade his coalition partners to pass the 1949 Republic of Ireland Act. This was really just a change of name, since the new republic’s jurisdiction remained the same as previously, and its constitution was still the one drafted by de Valera in 1937. Nonetheless, the political initiative had been seized from a leader who, in spite of sixteen years in power, had not moved on partition. Ulster Unionists reacted with predictable anger, and Westminster passed legislation guaranteeing Northern Ireland’s position within the United Kingdom until its parliament decided otherwise.

This copper-fastening of partition provoked an outcry in the South. The government formed the Mansion House Committee, an all-party anti-partition body. Fianna Fáil participated, though de Valera had little enthusiasm for initiatives that he did not himself originate or control. His preference for the larger stage was demonstrated by his departure on a speaking tour of Britain, Australia, New Zealand and the United States. In the US he voiced some of his most virulent attacks on partition. In Boston, he likened unionist rule to Soviet dictatorship in Eastern Europe:

‘If what is happening in Ireland today were being done in Eastern Europe by Russia, the people on whom it was being perpetrated would be entitled to call for assistance, and those who talk of democracy would cry out against the injustice’.

Yet when he returned to power in 1951 he indulged in little more than verbal gestures on partition, and the Mansion House Committee was allowed to lapse.

The Arborfield raid

Inert though Irish politics were in the post-war period, there was enough prevalent rhetoric to fuel expectations on partition that, if not met, could lead to violence. The republican movement began to regroup and return to the fray; Sinn Féin reorganised itself, and the United Irishman newspaper was launched in support. At the 1949 Bodenstown commemoration, a resolution was passed re-committing the IRA to ridding Irish soil of what it described as the ‘invader’. The resolution went on to declare that ‘our policy is to prosecute a successful military campaign against the British forces of occupation in the Six Counties’. This was later re-worded to make it clear that such a campaign would not include hostility towards the Dublin government, and in 1954 the Army Council of the IRA issued this as a standing order.

Seán South (circled) marching in the 1956 Easter Rising commemoration in Limerick. At the bottom left-hand corner is the badge worn by all IRA volunteers during the 1956–62 border campaign. (Des Long)

In June 1951 the Army Council sanctioned operations against army bases in Northern Ireland and Britain, primarily to seize weapons and ammunition. Some of these actions were carried out with panache and caught the headlines, notably a raid on an army depot at Arborfield, Berkshire, in August 1955, where 82,000 rounds of ammunition were seized. It was only bad fortune that allowed the haul to be retrieved by the police as the raiding party dispersed. Other raids earned heavy sentences for Cathal Goulding and Seán Mac Stiofán, who later became key figures in the 1969 IRA split.

Saor Uladh

At this time the IRA was uncertain about its military strategy, but in November 1956, to coincide with Remembrance Sunday, a dozen attacks were launched along the border over a distance of 150 miles. These were the work of Saor Uladh, a breakaway group founded by Liam Kelly of Pomeroy, Co. Tyrone. Saor Uladh had a lively history. On Easter Monday 1952 Kelly and his men took over Pomeroy, cut telephone lines and set up roadblocks. From the top of an empty porter barrel Kelly dramatically read out the 1916 Proclamation to a dozen bewildered passers-by. Next day the incident made the Dublin newspapers and was termed ‘a republican operetta’. By now the group was commanded by Joe Christle, a maverick figure who had been expelled by the Army Council. Christle, educated by the Christian Brothers, the holder of a law degree and a well-known cyclist, had been influenced by the EOKA campaign in Cyprus and favoured the bombing in Northern Ireland of dancehalls, pubs and cafés patronised by security forces. He found little public support for this during his group’s short-lived campaign.

When the Army Council’s strategy for a new offensive eventually emerged, it comprised planned attacks not just on border installations but also on RUC and army barracks in Belfast. In mid-November 1956, however, Patrick Doyle, a long-serving Belfast activist, was arrested in possession of documents that spilt the beans. As a result, the Army Council abandoned its Belfast design; there had been doubts about this anyway, based on fears of a Loyalist backlash against nationalist areas and uncertainty about the IRA’s ability to defend these. Thus the offensive that was launched on the night of 11–12 December was a border campaign only. It was code-named Operation Harvest and directed by a former Irish Army officer turned journalist, Seán Cronin.

Brookeborough

None of its incidents gained more notoriety than the Brookeborough raid. The IRA unit involved had been lying low in Fermanagh for several days beforehand and was led by Seán Garland. It was his decision to hit the barracks, but he had only an old town-planner’s map of the village and was unaware that the post provided security for the Colebrook estate, home of the Northern Ireland prime minister, Sir Basil Brooke, a few miles away. It was thus strongly armed and guarded. Garland had over a dozen men and before the raid had requisitioned a lorry owned by a Lisnaskea building firm. Its driver, Leo Morton, was forced to drive towards Brookeborough; after a few miles he was bound, gagged and left lying in a field.

Garland’s ordnance included mines that he had primed and batteries to provide current to detonate them. The strategy was to park the lorry by the barracks and make a direct assault. The unit was split in two: an assault party to lay the mines and a fire party to provide cover. Two lookouts, Mick Kelly and Mick O’Brien, were dropped at the outskirts and instructed to give signals should RUC patrols or reinforcements approach. This arrangement was problematic; neither had much knowledge of the area nor of the side-roads that led into the village.

Moving up the main street, the driver, Vince Conlon, had difficulty locating the barracks; its only identifying features were the sandbags on its windowsills. It resembled an old schoolhouse, with one gable abutting the street and a central porch. He pulled up beyond the gable, but too close in to give the firing party sufficient sweep to cover the upper windows. The assault team ran to the front wall to lay a mine. At this moment, RUC sergeant Kenneth Cordner came out to investigate. He saw the mine being laid and ran back inside, slamming the door. A heavy fusilade spattered the building. He sprinted upstairs to fetch an automatic. Outside, Seán South was letting off his Bren gun, which stood on a tripod, while Paddy O’Regan fed him the magazine. South was stymied, however, because he was too cramped to properly direct his weapon at the higher windows. And it was from one of these that Cordner now returned fire. Behind the lorry, Daithi Ó Conaill turned on the juice to set off the mine, but nothing happened. With the unit coming under heavy fire from the barracks, and particularly from its upper windows, Ó Conaill was forced to make a suicidal dash to lay a second mine. He succeeded, but again it failed to detonate. In frustration he fired his Thompson gun into both mines; still they failed. They had been incorrectly wired.

When Cordner reached the upper room, he had difficulty in finding his Sten gun as the lights had been shot out. On his knees, he crept towards the gun rack and edged towards the window. He could see the lorry below, the IRA men milling around and firing at the building. He poked his weapon out and squeezed off a few rounds in a wide arc. Garland and Ó Conaill returned fire, and someone—possibly Fergal O’Hanlon—tossed a hand grenade at the window; it hit the sill and bounced harmlessly into the street.

Cordner now acquired a second magazine, while bullets rained through the window, showering him with glass. He poked his gun out again and this time could see the assailants more clearly. He let off a well-directed burst that had a deadly effect on the attackers. When he looked again, South lay slumped on his Bren gun, O’Hanlon (who had been throwing Molotov cocktails) was bleeding on the ground and O’Regan was lying face downwards after being shot. Garland was limping, having taken a bullet in the leg. It was now obvious that the game was up; Garland shouted to the men to pull out.

The getaway

Pulling out was easier said than done. In the lorry’s cab, Conlon had been hit in the foot and Phil O’Donovan, sitting beside him, was grazed. The lorry resembled a sieve: the cab was riddled, the sideboards peppered with holes, two tyres were burst and the tip-gear had been perforated. This latter mishap meant that the tailpiece bobbed up and down—to the discomfort of the injured—when the driver accelerated. After a few false starts, the vehicle made off down the street, wobbling crazily and only stopping to pick up the lookouts.

The rear of the lorry looked like an abattoir. There was little doubt that South was dying and that O’Hanlon was almost gone too. Somehow, Conlon drove on for five miles. He stopped at a place called Altawark (also known as Baxter’s Cross) and those who were able stumbled out. It was realised that the RUC would be in pursuit and that the barracks at Roslea, which lay ahead, would be alerted.

The bullet-riddled interior of the truck. (Des Long)

The men had to make a quick decision about South and O’Hanlon, who plainly could go no further. The rest of the journey would be on foot, over rough terrain towards the border. A deserted farmhouse and cowshed were spotted; it was decided to leave the wounded men in the shed and request local people to call a doctor and a priest. This was done, but Garland became reluctant to leave. He wanted to stay in the shed with a gun, so that he could make a fight of it with the oncoming RUC and gain time for the rest to get away. With difficulty he was dissuaded, and with the rest retreated up a hill in the direction of the border.

Ten minutes later, the RUC drove up in two Land Rovers and moved in on the abandoned lorry. From the hill, the men could see the RUC raking the vehicle with machine-guns. A few minutes later they heard a long burst of gunfire from the direction of the cowshed. Afterwards some said that this was the coup de grâce being administered to South and O’Hanlon. But the bullet holes in the shed were waist high and could not have hit the wounded men, except by ricochet. It was conceded that firing on the shed constituted a standard military tactic, employed when an oncoming force approached cover held by an enemy. This explanation was not, however, accepted by IRA activists, who have held, with great bitterness, that South and O’Hanlon were ‘finished off’ by the RUC. At the subsequent inquest in Enniskillen, RUC Inspector W. D. Wolesley said that John South (sic) was past medical help when found but that if O’Hanlon had received first aid he would have been saved. A search had revealed, he said, that the raiders had a first-aid kit with them, ‘but far from helping the unfortunate man, his comrades abandoned him and left him to die’—a claim later repudiated by the IRA.

The survivors successfully evaded pursuit by getting into the Slieve Beagh Mountains; on taking a compass bearing they headed for Monaghan. It was a long and hard slog; the RUC set off flares over the area and helicopters hovered overhead. Some of the wounded had to be carried and they often had to lie in the bracken to avoid being spotted. The ordeal lasted six hours before an advanced scout reported that they had crossed into the Republic. They had successfully avoided 500 RUC men and B-Specials who had scoured the mountains with baying hounds and airborne units.

The men’s luck ran out, however, when they crossed the border. On leaving the wounded in a friendly house, the remaining eight were picked up by a Garda patrol, but not before they had dumped their arms. The wounded were taken to hospital to recover and await trial, the others to the Bridewell in Dublin. All twelve refused to recognise the court and got six months in prison under the Offences Against the State Act.

Aftermath

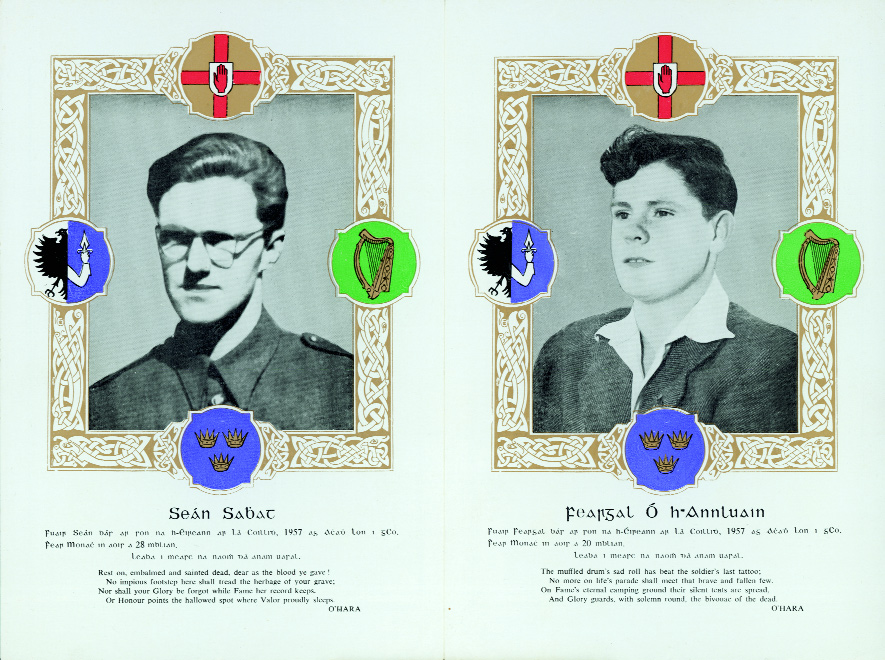

The raid made immediate headlines and within days South and O’Hanlon were seen as martyrs. In true Irish tradition, the ballad-makers set to work. Like Father Murphy of Boolavogue in 1798, and Kevin Barry during the Tan War of 1920, the names of South and O’Hanlon were added to the national repertoire. This was not surprising, as no tradition runs deeper in Irish history than the turning of physical defeat into spiritual victory.

The following week was almost an occasion of national mourning as the coffins—draped in tricolours—were taken across the border. As South was carried to Limerick the hearse was stopped en route as Mass cards piled up and overflowed on the breastplate. On arrival at midnight the cortège was met by the mayor and 20,000 people. Next day more than double that number were present at the interment in Mount St Lawrence cemetery, where a ‘Last Post’ was sounded and a volley fired by men in black berets.

The funeral of Fergal O’Hanlon to St Macartan’s Cathedral, Monaghan. (An Phoblacht)

In the weeks that followed, the characters of the dead were scrutinised. Nineteen-year-old Fergal O’Hanlon from Park Street, Monaghan, a draughtsman with the local county council and the subject of another well-known ballad by Dominic Behan, was seen as a fine young fellow who had played senior football for Monaghan and had a host of friends. He had impressed all who knew him as a solid young man. South, a 27-year-old clerk in a timber-importing firm in Limerick, was seen as something special. In many ways he resembled Patrick Pearse, whom he had admired. Deeply religious, dedicated to the revival of the Irish language and to traditional music, he was well liked by all shades of opinion. He was also highly talented: he painted in oils and drew cartoons for local newspapers; he ran his own magazine, An Gath (The Sting), and played the violin with professional competence. In the last issue of his paper he penned a piece entitled ‘Jacta alea est!’ (‘The die is cast!’), in which he said: ‘. . . there is an end to foolishness; the time for talk is ended’. Then he left Limerick for the border. Today his memory is embalmed in the famous ballad.

Big claims were made for the IRA’s attacks, not least by Moscow’s Pravda, which on 4 January disputed Downing Street’s dismissal of them as isolated incidents without popular support. It saw the raids as part of a bigger picture: ‘Irish patriots’, it declared with Cold War testiness, ‘cannot agree with Britain in transforming the Six Counties into a military base for the Atlantic Alliance’.

Once the initial attacks were launched, de Valera was quick to call upon Taoiseach Costello for firm measures against the IRA. This was politically difficult for Costello, given his government’s dependence upon Clann na Phoblachta. His government did, in fact, fall shortly afterwards on a related issue. A fresh general election was called for March 1957. Sinn Féin candidates, despite their pledge not to enter the Dáil, won four seats and nearly 70,000 votes. This was proof positive of a significant measure of support for republicanism, heightened no doubt by the emotions generated by the funerals of South and O’Hanlon.

After the Brookeborough raid, the IRA’s campaign became increasingly sporadic and only limited manpower was committed. Each operation had to be judged against Stormont’s superior forces and the resources it could deploy. These included 4,000 full-time RUC men, plus a B-Special reserve of 13,000, and a substantial British army back-up. The campaign was finally abandoned on 26 February 1962.

Kevin Haddick Flynn is a London-based writer and lecturer.

Further reading:

M. Anderson and E. Bort, The Irish border (Liverpool, 1999).

J. Bowyer Bell, The secret army (London, 1970).

T.P. Coogan, The IRA (London, 1995).

C. Ryder, The RUC 1922–1997 (London, 1989).