A seamless robe of Irish experience’: the First World War, the Irish Revolution and centenary commemoration

Published in Issue 4 (July/August 2014), Platform, Volume 22

The First World War was the most pivotal event in modern Irish history. Arguably few other European nations were as fundamentally transformed by the war as Ireland was, and the island as we know it today was formed to a great extent by the conflict. Well over 200,000 Irishmen served in the British forces during the war and at least 35,000 of them lost their lives on the Western Front and elsewhere. The figures for the fallen, of course, don’t take into account the tens of thousands of Irishmen who survived the fighting but were physically disabled or psychologically traumatised as a result of their military service. Nor do they give us any real idea of the intense bereavement suffered by families across the island when sons, brothers and husbands who had joined up failed to return home. In terms of the home front experience, the First World War was an all-consuming conflict in which virtually every component of society was geared towards the taking of enemy lives. The sense of being drawn into a colossal imperial war effort may have been less acute for Irish civilians than for their British counterparts, but many Irish people, from all communities and walks of life, actively supported the Allied struggle against Germany and the other central powers. Men and women from both unionist and nationalist backgrounds were consistently encouraged to ‘do their bit’ by their political and religious leaders between 1914 and 1918. And while their support may have waned to some degree from 1916 onward, the conflict was consistently sold to nationalists as an ‘Irish’ war in which Irish interests were at stake. Serving in the British forces or manufacturing arms and munitions for those forces were thus a lot less problematic for many Irish people than they appeared in retrospect. Moreover, although we still tend to lose sight of this, the post-war paramilitary violence and political turmoil that defined life on the island in the three years after the Armistice resulted directly from the events that occurred and the attitudes that evolved during the world war. To put it mildly, then, the impact of the First World War on Irish political, social and cultural life was profound and long lasting, and the legacy of the ‘war to end all wars’ is still very much with us today.

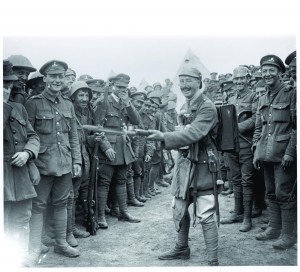

Royal Dublin Fusiliers celebrating their victory at the Battle of Wijschate-Messines Ridge, June 1917, where they fought as part of the 16th (Irish) Division alongside the 36th (Ulster) Division. (Imperial War Museum)

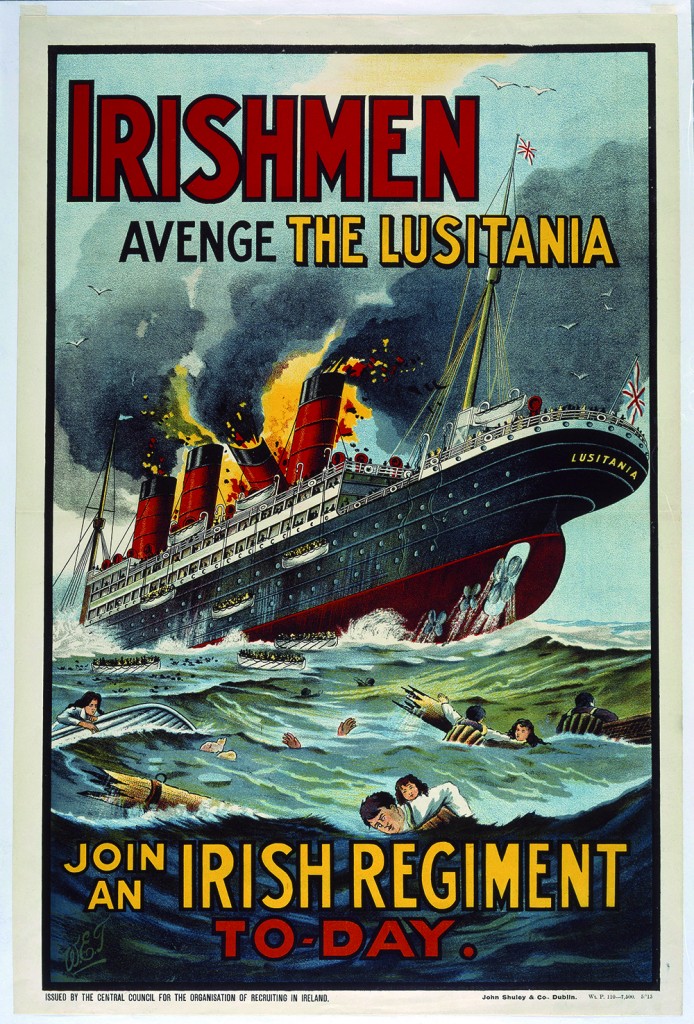

A key reason why the war was so transformative for Ireland is that one of the many dramatic events that formed the European arc of experience between 1914 and 1918 was the Easter Rising. The Rising—an undeniably foundational, nation-making event—would not have occurred and cannot be fully understood outside the context of the First World War. The nationalist rebellion that erupted in Dublin in April 1916 was as much an event of the world war as the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915 or the Arab revolt in which T.E. Lawrence was involved. It was comparatively small in scale, and took place on the periphery of the industrialised killing on the western and eastern fronts, but it was nonetheless part of the chain of violent episodes that made up the global conflict. Unless we place them in the context of a world war in which the British state was deeply invested, we cannot properly comprehend the British response to the Rising, the subsequent rise in republicanism, the success of the Sinn Féin party in 1918, the First Dáil, partition and the War of Independence. These events, these phenomena, gave birth to modern Ireland and they were all either part of or inextricably linked to the First World War.

Pasted underneath is a recruiting poster, ‘Will you make a fourth?’ (Trinity College, Dublin)

I am by no means the first person to highlight the overlapping nature of events in Ireland and Europe during the decade of the First World War. Keith Jeffery put it particularly well when he suggested that the republican revolution that began in 1916 and the world war ‘constitute a seamless robe of Irish experience’. Yet despite the Rising’s fairly indisputable place within the wider narrative of the Great War, there is a persistent popular view that the two were separate, only vaguely related events. And while there are signs that this may perhaps be changing, we still clearly fail to acknowledge the links, at both the political and more personal levels, between the Irish War of Independence and the global war that preceded it. In terms of commemoration, the traditional tendency has been to remember either the Irishmen who served in the British armed forces on the Western Front and elsewhere or their com-patriots who fought in the Easter Rising and in the post-war guerrilla campaign. Which groups we identified with usually depended on which community we came from, or our political understanding of the past and present. The implication of all of this divided commemoration was that the men and women who struggled for Irish independence really had nothing to do with those who supported the British war effort. One group was invariably commemorated at the expense of the other. Despite some very encouraging gestures of conciliation in North/South and Anglo-Irish commemoration over the past fifteen years or so, there is the danger that this will continue as we move through the centenaries. In other words, there is a risk that over the next few years, and es-pecially in 2016, people will choose to commemorate either the Irish Revolution or the First World War and will fail to recognise the profound connection between the two. The problem with this approach is that it is both unhistorical and needlessly divisive. As we enter into a period of intense commemorative activity in Ireland and across Europe, it is thus worth considering some of the ways in which the ex-periences of the ancestors that we have traditionally divided were in fact very closely interconnected.

Proclamation taken from the walls of the GPO.

(Trinity College, Dublin)

The First World War was a moment of completely unpreceden-ted violence in which the men who took up arms experienced a radically new and extreme form of warfare and died in their millions on the various fighting fronts. For the civilian populations on the home fronts the process of mass slaughter led to widespread loss and bereavement. This common experience of familial grief is one of the ways in which the world war and the Irish Revolution are closely connected, and it is also something that potentially binds disparate communities together. A small number of examples illustrate this point quite well. For a lot of Irish people Éamonn Ceannt, one of the seven signatories of the proclamation of the Irish Republic, is a reasonably well-known figure of the Easter Rising. He led the unit of volunteers that held the South Dublin Union throughout Easter week and was executed for his part in the rebellion on 8 May 1916. Readers may be less familiar with his brother, William Kent, a company sergeant-major with the Royal Dublin Fusiliers who was mortally wounded during the Battle of Arras on 24 April 1917, exactly a year to the day after the Rising broke out in Dublin. Some of the heaviest fighting of the Rising took place around Mount Street bridge, where the Sherwood Foresters suffered over 200 casualties as they attempted to cross the Grand Canal. An insurgent officer named Michael Malone was killed when British units finally overwhelmed the rebel positions. Michael’s brother, William, had been killed just over a year earlier while serving as a sergeant with the Royal Dublin Fusiliers during the Second Battle of Ypres. While grief may be publicly expressed, it is often felt at an intensely personal level, especially by widows or parents who outlive their children. Are the Kent and Malone families likely to have been less bereaved by the loss of any of these men because of the circumstances in which they were killed? It is difficult to say, but it is certainly inappropriate for us, 100 years later, to suggest that the lives of two of these long-dead Irishmen were somehow worth more than the other two. If we pause to consider all of this from the British perspective, the universal nature of grief in wartime arguably becomes even clearer. Over 130 ‘British’ soldiers were killed during the Rising. Some of these men were Irish, but most were from different parts of Britain. For a family from Nottingham, say, was the loss of a son or husband less tragic or painful because he was killed and buried in Dublin rather than in Flanders or on the Somme?

Moving forward to the War of Independence, several republicans who were active in the military and political struggle had lost brothers on the Western Front, including Kevin O’Higgins and John Joe Sheehy of the Kerry Brigade of the IRA. The familial relations between those in the republican movement and the men who had served in the British forces partly explain why numerous Irish veterans of the world war went on to join the IRA. Many of us know the basic details of the British army or navy service of men such as Tom Barry, Emmett Dalton and Erskine Childers, but we tend to regard them as curious footnotes in the story of their fight for Irish in-dependence. Historians who have commented on Irish servicemen who subsequently fought in the IRA have generally dismissed them as a mere handful of renegades. Recent research has revealed, however, that in excess of 100 demobilised veterans of the British forces served in the IRA between 1919 and 1921. This may not seem like many in the context of the more than 200,000 Irishmen who wore British uniforms during the world war, but they were a significant presence in a guerrilla army that at most numbered about 3,000 men. The witness statements recorded by the Bureau of Military History in the 1940s and ’50s are littered with references to ex-‘British’ servicemen who either served in the IRA or in some way supported the republican cause. There were even a small number of individuals who served on both sides but did so the other way around, so to speak. Patrick Dalton and Michael McCabe were both about sixteen when they fought with the rebel forces during the Easter Rising. The two boys were released shortly after the surrender on account of their youth; both later joined the British Army and saw active service during the world war. The significant number of Irishmen who fought both in the foreign theatres of the Great War and in the domestic battleground of the Irish Revolution should make us think twice about taking an ‘either/ or’ approach to commemoration as the centenaries unfold.

The nationalist rebellion that erupted in Dublin in April 1916 was as much of an event of the world war as the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915. (Trinity College, Dublin)

For if we continue to see the First World War and the Irish Revolution as separate events, there’s a danger that while we may well remember our ancestors during the centenaries we won’t understand them. And if we believe that our ancestors are worth remembering, then we should be prepared to try to make sense of their complex experiences. This means going beyond simply focusing on men who took up arms and remembering that tens of thousands of Irishwomen, and indeed children, were caught up in the turbulent events that occurred a century ago. Between the outbreak of the world war in 1914 and the end of the Civil War in 1923, women from across the island, and from every conceivable social and cultural background, both supported violence and were themselves the victims of it. As we set out to commemorate, we would also do well to remember that civilians, of whatever gender or background, were the primary victims of both the Easter Rising and the War of Independence. In Ireland, as in most of the rest of Europe, we have a commemorative culture that focuses almost exclusively on those who died in war. Yet in the years ahead we should also remember those who did not die but were nonetheless bereaved or affected in some other profound way by the violence that raged around them. Mourning widows, parents and children, along with a multitude of disabled and traumatised veterans, deserve our attention, and our empathy, at least as much as the men who died or were mortally wounded in combat.

Finally, there is the thorny issue of bringing the broad Irish traditions of unionism and nationalism together in a meaningful way during centenary commemoration—or, at the very least, avoiding exacerbating tensions between the two. Over the past twenty years or so there has been a remarkable resurgence of interest in Irish military and civilian participation in the First World War in the Republic of Ireland and among nationalists in the North. This has led to some very encouraging moments of cross-community commemoration and conciliation. Yet whatever about the rest of the population waking up to the experiences of Irish servicemen who served at Gallipoli and on the Somme and elsewhere, unionists understandably have little interest in remembering the Easter Rising or the War of Independence. The legacy of the centenary commemorations—both for cross-community relations and simply in terms of our understanding of the past—will depend on the spirit in which we enter into them. Where possible, therefore, it is perhaps more interesting and more positive to focus on individual ex-periences and personal relationships rather than on communities or nations or states. The tone with which we express our understanding of the past is also crucial. The events of a century ago have passed out of living memory, so we should ideally look back on them less with a querulous sense of competition and more in an open-minded spirit of empathy for our ancestors and curiosity about the world in which they lived and died.

Edward Madigan is Lecturer in Public History and First World War Studies at Royal Holloway, University of London.