SCHOOLS’ ESSAY COMPETITION: The killing of RIC Sergeant Henry Cronin, October 1920

Published in Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2021), Volume 29An event that encapsulates the intricacies of conflict during the War of Independence.

By Aisling Gallagher

In the period 1919–21, Offaly seemed relatively quiet when compared with hotbeds of rebellious activity such as Cork, Tipperary or Kerry. In fact, there were consequential attacks and ambushes carried out by not one but two Offaly IRA brigades, but these garnered little acclaim or recognition because the Offaly IRA was not as well organised as its counterparts in more active counties.

Background—the ‘Tullamore incident’, March 1916

In 1916 Tullamore was a relatively peaceful town, with members of the RIC respected for their policing role. At the same time, however, a quiet but determined Irish Volunteer movement was growing in the town. This came to a head on 20 March 1916 in an event known locally as the ‘Tullamore incident’. A large crowd of hostile locals who had family members serving in the British Army gathered outside the Sinn Féin hall on William Street, where a meeting of Cumann na mBan and Irish Volunteers was under way. Violence ensued, and a group of RIC constables were dispatched to the scene to disarm the men inside the hall, which was then thoroughly searched for arms. Sgt Philip Ahern was seriously wounded and lucky to escape with his life; the bullet wound ‘placed his life in danger for several weeks’. Ahern, reputedly a popular member of the force, never returned to work and was forced into early retirement at the age of 56, after serving the town for 34 years. He was replaced by Sgt Henry Cronin.

The years between 1916 and the end of the War of Independence in 1921 saw an exponential growth of public distaste for Crown forces in Ireland. Within a year of the Rising, membership of Sinn Féin had increased tenfold. With de Valera newly elected as president of Sinn Féin and also of the Irish Volunteers, for the first time the political and military wings of nationalism were under one figurehead. When the War of Independence began in 1919, Irish people no longer followed the governance or advice of the Crown forces but looked instead to Sinn Féin for leadership. The death of Terence MacSwiney, lord mayor of Cork, on 25 October 1920 was one of the most tumultuous events of the conflict and was followed by extended expressions of grief, both in Ireland and worldwide, as his sacrifice was recognised.

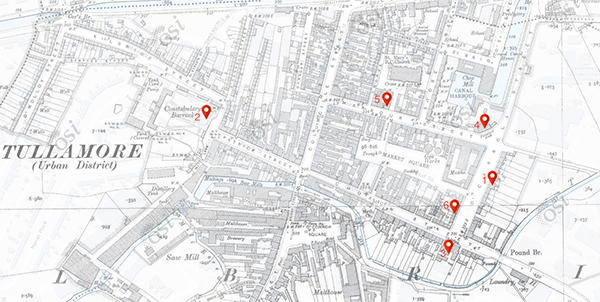

Above: Ordnance Survey of Ireland (OSI) map of Tullamore (1913), showing: 1, Sgt Cronin’s home; 2, the RIC barracks; 3, the county infirmary, where Cronin died; 4, the Foresters’ Hall, burned by Black and Tans as a reprisal after the shooting; 5, Heavys’ lodging house, where James Connor, president of Tullamore Trades’ Council, was arrested—and escaped; 6, 4 Henry/O’Carroll Street, where the author’s grandparents live.

Tullamore was no different in its response to MacSwiney’s death. Under Sinn Féin instruction, a boycott of military and police forces was put in place in the days following his death. The outlook of Tullamore residents had shifted completely since 1916, and the death of MacSwiney was a turning point in the conflict.

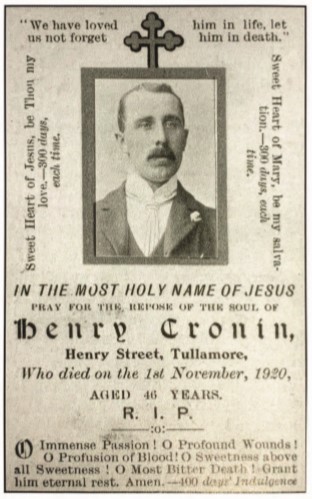

RIC Sergeant Henry Cronin

Henry Cronin was born in County Cork in 1874. (RIC officers were not permitted to be stationed in their county of birth in order to limit local influence.) He had previously been stationed in the south of the county in Moneygall. He had moved into a house on O’Carroll Street, or Henry Street as it is more commonly known, near the centre of town (OSI map, 2). Sgt Cronin was accepted by the vast majority of Tullamore residents as a genuine and trustworthy policeman who was carrying out his duties in the relatively peaceable town to the best of his ability.

Henry Cronin was born in County Cork in 1874. (RIC officers were not permitted to be stationed in their county of birth in order to limit local influence.) He had previously been stationed in the south of the county in Moneygall. He had moved into a house on O’Carroll Street, or Henry Street as it is more commonly known, near the centre of town (OSI map, 2). Sgt Cronin was accepted by the vast majority of Tullamore residents as a genuine and trustworthy policeman who was carrying out his duties in the relatively peaceable town to the best of his ability.

Sgt Cronin had been playing Hallowe’en games with his children on the evening of 31 October 1920, but what had begun as a night of joy and innocence suddenly took a dark and horrifying turn. It was reported that Cronin’s wife heard gunfire on the street outside at approximately 7.45pm, minutes after her husband had left the house to walk to the RIC barracks (OSI map, 4), where he was due to report for duty. She ran out and found him lying on the street gravely wounded, exclaiming ‘I’m shot, I’m shot’. The shots had been fired at close range, as Cronin’s clothing was singed. He told his wife that he had been armed when he was shot but that his revolver had jammed and he was unable to return fire (Midland Tribune, 6 November 1920).

The county infirmary at the time was in a building that still stands at the end of Henry Street (OSI map, 3), approximately 50 yards from the Cronins’ home, and a nurse was hurriedly sent for. Cronin had been shot three times—once in the chest and twice in the stomach—and his right arm was also shattered. As the nurse was treating Cronin—who by now had been carried onto a sofa in his home by neighbours—messengers were dispatched to send for a priest. The parish priest, Fr Lynam, arrived to hear the wounded man’s confession. Cronin was subsequently transported the short distance to the county infirmary, where he passed away at approximately 4.40am the following morning (1 November).

At the inquest following his death, the coroner, a Mr T. Conway, said of Cronin that ‘the deceased never interfered unduly with the civilian population, but simply did his duty’ (King’s County Chronicle, 4 November 1920). The sergeant’s relationship with the town was encapsulated in a letter penned by his son in 1989 on the anniversary of the killing in which he said that his father ‘was over-confident. He knew and was friendly with everyone’ (Irish Times, 2 November 2000).

Why was he killed?

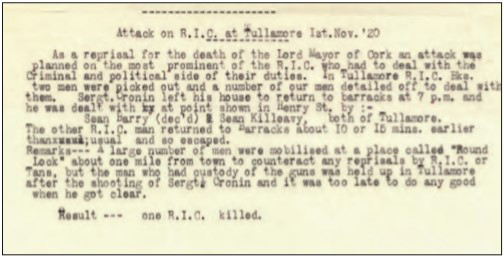

The death of Sgt Cronin illustrates how an incident replete with everyday familiar local detail can be seen within the wider context of War of Independence activity at county and national level. The location and timing of his killing—on the street in which he lived, the street on which his children played—demonstrates how the familiar can turn to the fatal in the blink of an eye. The identity of the perpetrators and the reasoning behind the killing would remain a matter of speculation and rumour for almost 100 years. In early 2019, however, ‘brigade activity reports’ of IRA units during the War of Independence were compiled and released to the general public by Military Archives. The events of the night of 31 October 1920 are recorded in the activity report of the 1st Offaly Brigade (p. 40), which tells us that an attack was planned on prominent RIC officers as a reprisal for the recent death of Terence MacSwiney. In Tullamore two RIC officers were selected as targets, and a plan was put in place whereby several local IRA men were detailed to ‘deal with them’. The report goes on to tell us that Sgt Cronin, one of the officers chosen, was shot by Seán Barry and Seán Killeavy, both Tullamore residents. The other RIC officer, who remains unnamed, escaped his fate because he returned to the barracks ‘ten or fifteen minutes earlier than usual’.

Brigade activity report of the IRA’s 1st Offaly Brigade for the night Sgt Cronin was shot. (Military Archives)

Reprisals

Henry Street was quickly abandoned as word of the shooting spread and was like something out of a ghost town by 10pm. Reprisals for the shooting of Cronin were carried out by the Black and Tans and began approximately three hours later at 11pm. Thousands of pounds’ worth of damage was inflicted upon the town’s people. Most notable was the burning of the Foresters’ Hall at the end of Henry Street (OSI map, 5). The Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union hall was wrecked and their band instruments destroyed. The offices of the Offaly Independent were also ravaged, with the type racks and type cases smashed. The Black and Tans continued their reprisals throughout the night and the houses of several IRA sympathisers were visited, such as the shops of Mrs Wyer and O’Brennan’s on Church Street. One of the most remarkable events of the night was the 4am visit to the lodging house of James Connor, president of the town’s Trades Council (OSI map, 6). Connor was dragged out of bed, still in his sleep attire, and was taken into custody. The landlady pleaded with his captors to allow Connor to procure a coat, and this temporary release afforded Connor the chance to escape through a back entrance to the property (King’s County Chronicle, 4 November 1920).

The short period of time between the shooting of Cronin and the commencement of the reprisals (approximately three hours) proved a point of confusion when researching the event. It is difficult to comprehend how a town could be transformed into something like a war zone in a matter of hours, with the burning, ransacking and destruction of thousands of pounds’ worth of property. One has only to examine the newspaper reports of the weeks preceding the event, however, to gain a true insight into the state of affairs in the town. An article entitled ‘Warnings in Tullamore’ regarding the week before the events of the 31st details notices that were received by post on the Friday morning of the preceding week by several prominent men in Tullamore. The notices were pen-printed and took up no more than one piece of paper. Each read ‘Warning: Beware, you are a doomed man. Clear out.—Red Hand’. Each concluded with a sketch of a skull and crossbones. On the same day, notices were hung up around town and sent to notable traders, threatening reprisals unless the boycott of military and police forces was lifted within twelve hours (King’s County Chronicle, November 1920). It can be argued, therefore, that the attack on Sgt Cronin was only one of a number of complex factors that instigated the terrifying reprisals inflicted on Tullamore residents on the night in question.

Above: The county infirmary at the end of Henry Street, where Sgt Cronin died of his wounds on 1 November 1920, had become the Offaly County Library by the time this photograph was taken in 1980.

Epilogue

My grandmother (who lives at 4 Henry Street/O’Carroll Street, OSI map, 1), who is still deeply disappointed to this day that she never extracted the full extent of what occurred on 31 October from her father (my great-grandfather), Matthew Gallagher, told me of the devastation inflicted on the young Cronin family as a result of their father’s murder. She said that Matthew was uncomfortable when speaking of the event, and that the single aspect of the night engraved on his memory was hearing the screams of Cronin’s young daughter, Peggy, who ran away from the scene out the Daingean Road, or the ‘flat road’ as it was known to locals of the time (OSI map, route taken in red). Another aspect of this incident that interested me is the fact that the civilian population of Tullamore never spoke about the horrors of this death in any great shape or form. An article in the Irish Times in September 2000 by Tullamore native Conor Brady refers to the reluctance of the people of the town to talk about or accept the terror of 31 October 1920. Brady was horrified to witness Sgt Cronin’s son, Patrick, who became a bishop in the Philippines after devoting his life to the Columban missions, returning to Tullamore in the 1960s and 1970s to mass crowds, rapturous acclaim and celebrations; yet the children of the town, Brady included, had never been told about Patrick’s father being killed by local men on the street through which his son processed 40 years later. Brady remarked: ‘The murder of Sergeant Henry Cronin was simply not spoken of. It was [as] if he had never existed’ (Irish Times, 2 September 2000).

Members of the Cronin family played a respected part in Tullamore life for much of the twentieth century. One daughter, Kitty, won a scholarship in 1927 based on her Leaving Certificate results in the local Sacred Heart secondary school (Offaly Independent, 27 August 1927). And the aforementioned Peggy worked as a clerk in the respected local law firm of Hoey and Denning until her retirement. In 1955, when son Patrick was appointed a missionary bishop in the Philippines, the Offaly Independent wrote of him:

‘Monsignor Cronin’s elevation to Episcopal rank and dignity is a great honour, not only to himself and his family, but it is likewise a great honour to the historic town of Tullamore, proud to claim him as one of the most illustrious of her sons.’

(Offaly Independent, 20 August 1955)

The death of Sgt Henry Cronin reached its centenary in October 2020. The fact that this night, one of the most shocking in the history of Tullamore, was seldom discussed until recent years highlights the uncomfortable and distressing nature of deaths such as this during the War of Independence. Cronin’s death is only one small incident of the War of Independence, but it offers us invaluable insight into the cultural and societal context of the era—an era of secrecy, subversion and scheming on the part of those who supported the fight for Irish freedom, an era of indiscriminate reprisals by Crown forces, and an era of constant surprise, defence and being on the back foot for the men of the RIC owing to the opposing side’s guerilla tactics.

Aisling Gallagher was a student in Sacred Heart School, Tullamore.

FURTHER READING

R. Abbott, Police casualties in Ireland 1919–1922 (Cork, 2000).

M. Byrne, Tullamore in 1916 (Tullamore, 2016).