Royal College of Physicians

Published in Issue 6 (November/December 2015), Reviews, Volume 23

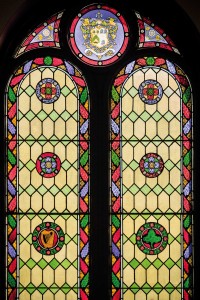

The stained-glass window in Corrigan Hall, which can seat up to 200 people.

The Royal College of Physicians is situated in an ornate building, erected in 1863 with the proceeds, it is said, of the insurance on the Georgian house that previously stood on that site and which was destroyed by fire. As part of a project to increase the use of the building and raise its profile, the College has recently started free guided tours for the public. Usually held each day at 1.30pm, it may be best to check ahead, as events in the College can lead to a postponement.

The building is worth a visit in its own right, with its columns, stucco and elaborate décor. Each room is named after a past president of the College, and their many portraits or statues are to be found throughout the house. Our tour begins with a brief history. The College was founded in 1654 and is a postgraduate medical organisation comprising members and fellows. It is a sister institute of the three Royal Colleges of Physicians in Edinburgh, Glasgow and London. The ‘royal’ comes from the charters granted in 1667 by Charles II and in 1692 by William III and Mary II. It was known as the King and Queen’s College of Physicians in Ireland until 1890, when, under a charter of Queen Victoria, it adopted the present title.

The tour then takes us through the various rooms, pointing out the portraits and other items of interest. In the first room is its only portrait of a woman, Dr Kathleen Lynn (1874–1955), who was a member of the Irish Citizen Army and chief medical officer during the 1916 Rising. Here also is the imposing president’s chair, which is used during graduation ceremonies. Don’t forget that this is a functioning educational institution and almost all the rooms are used for lectures or tutorials. The College is also available for weddings, however, and the president’s chair is a favourite among brides wanting their photographs taken. Also look out for two tables made of Irish oak on which past students have carved their names.

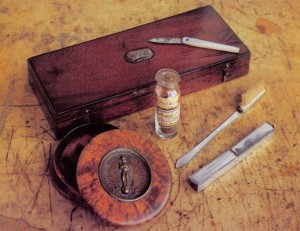

Napoleon memorabilia, including his toothbrush, donated to the College by the deposed emperor’s doctor on St Helena, Irishman Barry O’Meara.

As we go along the corridor, we stop at a small display cabinet that probably contains the most intriguing items in the College: Napoleon’s toothbrush and a fragment of his original coffin. These ended up here because Irishman Barry O’Meara (1786–1836) was appointed the deposed emperor’s doctor on St Helena. He was the first physician to perform a medical operation on Napoleon—extracting a wisdom tooth. He later displayed the tooth in the window of his surgery in London, we were told. O’Meara was the author of Napoleon in exile, or A voice from St Helena (1822), in which he charged Sir Hudson Lowe, the British governor, with mistreating Napoleon; it caused a sensation on its release. A copy of the book and related material is also on display.

As well as the College’s history, the tour guide also told us some of the ‘unofficial’ history, such as that of the three ghosts that are said to haunt the building, victims of the 1862 fire, and the death of President Erskine Childers (1905–74), who had a heart attack while giving a speech at the College. Another story is how the Irish state is obliged to donate eight corpses of executed criminals for dissection purposes, but as no one has been executed since 1954 there have been no corpses.

The Graves Room, named after the discoverer of the eponymous disease, hosts a pop-up café when not being used for lectures or meetings. Beyond this is the even larger Corrigan Hall, which can seat up to 200 people. The amazing thing about this is that it was a Real Tennis court, that indoor version of the game that dates back to Tudor times. Make a point of looking up at its ceiling. This impressive structure consists of interlocking sections of oak without any nails.

The library contains over 50,000 books, dating back to 1713, when Sir Patrick Dun bequeathed his personal library to the College.

(All images: RCPI)

I have to admit that I was most impressed by the library. The collection of over 50,000 books dates back to 1713, when Sir Patrick Dun bequeathed his personal library to the College. It forms part of the College’s emerging heritage centre (they plan to have a formal museum within two years). The room itself, with its long balcony and unique view of Kildare Street, is impressive, and the library holds the College’s archive, heritage items and genealogical research collections. The unusual thing is that almost every book is concerned solely with the history of medicine and medical education in Ireland. The whole collection is being methodically digitised and will one day be available on-line.

Easily overlooked because of its overbearing neighbours, the Royal College of Physicians offers a different take on Irish history and is full of interesting historical items, each with a story. It is keen to open up to the public and you are sure to find a warm welcome there. I came across it by accident but I’d recommend it as a place to visit.

Tony Canavan is editor of Books Ireland.