Revolving retailers: when ‘Woolies’ left Ireland, 1984

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 5 (Sept/Oct 2011), Volume 19

Woolworth’s original store on Dublin’s Grafton Street opened in April 1914. (3D and 6D Pictures Ltd)

On 25 July 1984 a wave of disbelief swept through the main streets of Ireland like a tsunami. Woolworth’s was abandoning Ireland! The shopping public reeled. F.W. Woolworth & Co. Ltd—also colloquially and affectionately known as ‘Woolies’—had been an iconic shopping experience for generations. It formed an integral part of urban folklore heritage. To witness its departure was like saying that Christmas had been cancelled.When news broke that this solid and dependable doyen of the Irish retailsector was to disappear from their midst, thousands of households found themselves significantly affected. Back in 1984 times were tough, with the economy in deep recession. With Woolworth’s gone from the Republic’s retailing sector, hundreds of valued shop-floor jobs would be lost and a well-structured, well-trained management corps dispersed.

Moreover, for many Irish manufacturers whose contribution to the Irish economy for the past 70 years had been reliant on supplying Woolworth counters with a range of goods, the loss of this lucrative and reliable market was serious.

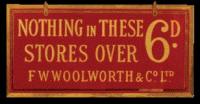

Woolworth’s slogan during the interwar period. (3D and 6D Pictures Ltd)

Shopping as a leisure pursuit

In April 1914, the arrival of an American-owned emporium of indulgence in Dublin’s Grafton Street marked the start of the expansion of Woolworth’s chain of ‘variety’ stores across Ireland. Under the management of a young man from Wexford who, in due course, would go on to blaze a trail as the company’s chief buyer of china and glass, this very first Irish branch of the chain was to be followed by 40 other identical outlets in every province of Ireland.The Woolworth ‘everyday stores for everybody’ were famous for promoting the idea that shopping could be a slow, pleasurable activity that offered customers of all ages and genders the opportunity of buying nice things at affordable fixed prices. ‘Nothing in this store over 6d’ was the slogan up to the Second World War, and the goods on open display counters that were priced from one penny upwards presented a mixture that combined practical housewares and hardware with more luxurious indulgences. The combined temptations of confectionary, ice-cream, toys and Hollywood-style cosmetics, matched by music departments that sold daring jazz records and stationery counters where—by accident—the occasional banned book turned up, brought an air of ‘cosmopolitanism’ and ‘modernity’ into the Irish main streets in the interwar period. By the mid-1930s Ireland’s small market town traders had learned not to be panicked by the onset of such exotic competition. Local shopkeepers cannily offered credit to established customers and announced bargains, fire sales and anniversary celebrations that offered ‘slaughtered prices’ for such items as ‘ladies’ drawers, chemises and aprons’. Meanwhile, Ireland’s provincial press waxed enthusiastic about Woolworth’s elegant mahogany counters and mirror-filled premises, which were not only ‘centrally heated but electrically lighted’, and forecast how the crowds of eager shoppers lured in to sample a new Woolworth branch would certainly boost the economic prospects of their local town. Even formerly lethargic critics enjoyed riding on the coat-tails of this excitement and, as time went on, a level of respect and admiration for Woolworth’s high ethical standards and support of local community activities developed. Business brought business. Excellent working conditions and career prospects for male and female employees were also recognised as a bonus in every new location. With 30 or more girls needed for each branch—backed up by a handful of young male trainees—hundreds of hopefuls queued for the chance of a ‘start in Woolworth’s’. These were jobs for life in what the company’s ethos liked to regard as a ‘family’ of colleagues.

Woolworth shop sold for £4.75m

In April 1984, almost exactly 70 years after Woolworth’s arrival, Dubliners woke up one morning to headlines announcing that the company’s Grafton Street branch was to close its doors for good. Only those in the know had heard the whispers. Few people noticed a small paragraph in the Irish Times on the previous day, 4 April 1984, which sounded an alert ‘by leaders of the shop staff USDAW [Union of Shop, Distributive and Allied Workers] that Woolworth is seeking buyers for 34 of its British high street chain stores’. What had been going on behind the scenes in the world of corporate finance and stock-market dealings was of little interest to most of the shoppers in Grafton Street. It had been a long-drawn-out saga that had involved the financial troubles of Woolworth’s American parent company since 1980, culminating in a deal that allowed their junior partner and former British subsidiary to become a stand-alone British firm under the control of a London consortium of financiers and developers. This deal in 1982 allowed the cash-strapped New York Woolworth company to save its bacon—albeit only temporarily holding off subsequent collapse—while the asset-rich F.W. Woolworth & Co. Ltd and its huge portfolio of valuable property in prime locations throughout the UK and Ireland was left to conduct its future under a new team. It was a neat solution. Nevertheless, when the members of this very different Woolworth board convened to take the helm in London, a fresh direction was envisaged. Ventures were planned that required reinvestment, and these new policies and strategies had to be funded. Old-style shop-keeping was not foremost on their agenda. The sale of the company’s valuable property holdings was. In the wake of the closure of Dublin’s Grafton Street branch, assurances were given that no further shutdowns in Ireland were imminent. This was true enough. The timing for these departures was to be excellently stage-managed later on.

Protesting voices carried little weight

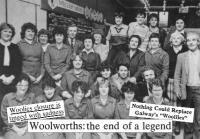

When the full list of closures was announced on 25 July the Dáil had already gone into summer recess. It would not reconvene until October, by which time Woolworth’s plans would be all completed. Semi-state bodies like Córus Trácthála Teo (CTT), which championed the efforts of many small manufacturing concerns supplying Woolworth’s, were also oddly silent. In 1981, CTT had forecast that the £2.5m worth of Irish-made goods sold from Woolworth counters per annum would rise to £7m in 1982 and had expected further growth to rise to £15m over the next five years. Such optimistic hopes were now dashed. Nonetheless, spokesmen from several Irish chambers of commerce voiced vigorous protests, and the regional press rowed in by marking each stage of the ground-level disputes between unions and the company. Headlines such as ‘Total shock’ were replaced by increasingly militant ‘Woolworth’s decision under fire’, ‘Court order against Woolworth sit-ins’, and ‘Woolworth staff lock out manager’. It was all in vain. Press support retreated into nostalgia: ‘Woolworth’s: the end of a legend’ or ‘Nothing could replace Woolies’.

Staff from Woolworth’s Drogheda store in 1984, with headlines from around the country. (Drogheda Independent)

Shoppers’ loyalty not easily beaten

Woolworth branches in Northern Ireland had been spared the falling axe. Rumour had it that high-level diplomacy in Westminster had regarded their presence in the province as a distinct asset. Consequently, by November coachloads of customers from the Republic began to trek across the border from all points south. As one report on the unprecedented level of trade being done by Newry’s Woolworth store put it, ‘the toys were leaping into trolleys’. Corporate finance and property speculation might indeed have been able to wield immense power over the lives of the small people who merely feature as ‘consumers’ like some anonymous and pliable blur—but for hundreds of families, Christmas shopping without a trip to Woolworth’s had been utterly unthinkable. HI

Barbara Walsh’s When the shopping was good: Woolworth’s and the Irish main street was published earlier this year by Irish Academic Press.