Revolutionary Justice – the Dill Eireann Courts

Published in

20th-century / Contemporary History,

Features,

Issue 3 (Autumn 1994),

Revolutionary Period 1912-23,

Volume 2

Dail Court in Westport, County Mayo.

‘This is the golden hour. Therefore be prepared.’ Thus did Austin Stack admonish the District Registrars throughout Ireland when, on 9 August 1921, he sent them detailed instructions on the procedures and regulations of the Dail Courts. No one was left in any doubt where the real authority lay: henceforth the parish and district courts were to be directly under the control of his Ministry. ‘Once the Courts are established’, Stack told the West Donegal Registrar, ‘Comhairle Ceantair have no authority over them (apart from helping litigants make contact or to boycott enemy courts) but otherwise Courts and Court Officials are completely under the jurisdiction of the Minister for Home Affairs and no other person has authority over them.’

Structure

A team of organisers-about ten men in all-were employed by the Ministry on a full-time basis and were assigned to specific areas: they supervised the election of justices, instructed the clerks in their duties and sent weekly reports back to headquarters. They had access to the local TDs and IRA brigade officers that were Stack’s eyes and ears in assessing the performance of the courts in every locality. Once established, the registrar was responsible for the operation of the courts in each parliamentary constituency which had its own District Court with a complement of five judges, of whom three was a bench. They were chosen by the parish justices. The latter, in turn, were elected by a convention comprising the Sinn Fein Club, the Trades Council, members of the rural or urban authority, the Volunteers and Cumman na mBan. While clergymen of any denomination were ex officio deemed to be eligible, it was more often that not the Catholic curate who presided at the Parish Court. These parish courts were central to the acceptability of the system.

Representative of the people

The justices were representative of the local people, and, therefore, answerable to them in a way a Resident Magistrate could never be. lt was considered a great honour to be elected, and for the most part, they appeared to have taken their duties seriously and were at pains to stress their judicial independence. Many litigants who were unsuccessful in their suit or who had fines levied against them were quick to complain to the Ministry and thus furnish future students with a wealth of information on the public response to this innovation. Whatever its faults-and they were many-the parish court provided a cheap and immediate access to justice and, moreover, it was ‘consumer driven’ in a way no court could possibly be today. Dail Eireann was anxious to attract to its own departments users of those services provided by the British administration and none more than to its courts. Stack, therefore, responded to many complaints by lengthy investigations and frequently seemed to interfere inappropriately in several instances. How did he came to have such a system of courts to preside over in the first place, even before the cessation of hostilities and the Truce? How could there exist an alternative judicial framework when he was only then in a position to furnish it with rules of procedure?

Arthur Griffith

Ad hoc tribunals

In a story studded with paradoxes, the most striking paradox was that the ‘Dail Courts’ were not established by Dail Eireann! The breakaway from the British or statutory courts had been made by separate communities but occurred almost spontaneously throughout the country in the previous year. While Griffith preached a self-governing administration of justice from 1905 and made it part of Sinn Fein policy, the Dail had taken few practical steps in its first year, apart from passing a decree in August 1919 to set up a system of ‘National Arbitration Courts’ which amounted to little more than an aspiration. The foundation, on which Stack built, had its roots in the agrarian disturbances in the West, where smallholders, impatient with the procedures of the Congested District Boards, and often reinforced by gangs of disaffected men, took advantage of the generally unsettled conditions to force landowners out of their property by terrorising them. Such lawlessness threatened to overshadow the confident expectations and national pride engendered by the victory of Sinn Fein candidates in the General Election of 1918 and the subsequent creation of Dail Eireann. It became necessary to take urgent steps to prevent a conflagration so local leaders in the community set up ad hoc tribunals to which disputes could be referred and settled with some degree of rough justice.

Self-policing

Conor Maguire-later to be a Chief Justice-who was then practising as a solicitor in Mayo wrote a first-hand account of this development in the Capuchin Annual in 1968. Similar tribunals sprang up in several places and at the same time the newspapers were reporting another phenomenon of self-policing. Groups of Volunteers took on themselves the role of village constable, ‘arresting’ persons who breached the peace

Austin Stack

or stole property: they even investigated crimes which were reported to them and began to conduct trials. The Freeman’s Journal of 4 June 1920 reviewed the work of the Volunteer patrols in twenty-one counties over the previous six weeks: it included dispelling a riot, punishing culprits for damage to property and recovering the proceeds of bank and postoffice robberies. They regularly policed race meetings and fair days. All of this was the subject of much comment not only in the House of Commons, but in the British and foreign press. In May 1920 the operation of the Land Courts was brought under the control of the Ministry of Agriculture and in the same month, Austin Stack circulated, by means of the Sinn Fein Clubs, details of a scheme for agreed arbitration procedures to be organised in districts and parishes. Meetings were held to elect judges and throughout that summer, proceedings were reported in the local newspapers under the heading ‘Sinn Fein Arbitration Court’.

Criminal jurisdiction

However, matters were brought a step further the following month when, on 29 June, Dail Eireann issued a decree establishing ‘Courts of Justice and Equity’ and authorising the Ministry of Home Affairs to establish courts having a criminal jurisdiction. While there is no explanation for the rapidity of the transition from one system to another, the Minister is reported as saying that the Arbitration Courts depended on the consent of both parties but that the country was in such a state at the present time that the people looked to the Republican Government for their law and equity and in a very short time they would have ousted the English courts altogether. It was therefore necessary to take immediate steps to set up courts throughout the country which would be competent to hear every class of case similar to the cases dealt with in English Courts of Petty Sessions and Courts of County Sessions and Assize so far as Civil Jurisdiction was concerned. In other words, the courts were to be organised nationally under the immediate authority of the Dail, they would correspond in jurisdiction to the courts established by statute and their decisions would be enforced by sanctions, if necessary. However, another year would pass before the ideal could be fully realised. Although a committee of lawyers met to draft the constitution and rules of the courts-the Judiciary-and four professional judges were appointed (with considerable optimism, ‘for life’); the state of the country Worsened and imposed considerable restraints on Stack’s plans.

British Soldiers on the roof of the Four Courts guarding the Liffey embankment

1920. (COURTESY OF THE BETTMAN ARCHIVE)

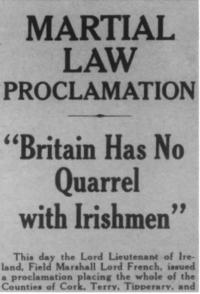

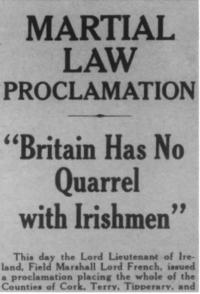

Enemy’ courts

In the meantime the so-called ‘enemy’ courts had also been adversely affected by the events of the previous year. There were over six hundred Justices of the Peace, many of them dignitaries in local councils, the majority having nationalist sympathies. A large number had resigned their commissions when the Troubles started or refused to serve on the Petty Sessions. The Resident Magistrates, who held their office at the pleasure of the lord lieutenant, were salaried officials and were mostly former military or police officers who were traditionally distrusted by the Irish people. As political violence increased, the Royal Irish Constabulary had to withdraw to barracks for their own safety, and under martial law, Crimes Courts or courts martial were set up to handle most offences, because witnesses refused to give evidence in the regular court; there were frequent press reports of Resident Magistrates adjourning the Petty Sessions because there were no cases to be heard. It was the same story with the Quarter Sessions which had jurisdiction to hear criminal matters before a jury. The few jurymen who might be minded to attend were turned back on the road by the IRA. When the judges of the High Court went out on the Assizes the courthouses were protected by sandbags and barbed wire and ringed by soldiers with fixed bayonets. Mr Justice Pim complained in Galway ‘that the control of the country and the law had become so weakened as to make it no longer possible to carry on’. However, with weary courage, the judges carried on as best they could but, increasingly, in courthouses emptied of all save lawyers, officials and police. Only in Dublin were they able to sit in conditions approaching normality.

The terror

Strangely enough, it was only in Dublin also that the professional judges of Dail Eireann were able to hold their courts as soon as the rules on procedure had been settled. James Creed Meredith KC and Arthur Clery, Professor of Law at UCD had been appointed to the Supreme Court of the Republic: Stack also secured the services of Cahir Davitt and Diarmuid Crowley-both of whom had been called to the Bar as recently as 1916-to act as Circuit Judges. However, by September 1920, martial law had been proclaimed over several areas and the Dail Courts suppressed, but all four still managed to hold some sittings in Dublin. The Circuit Judges were anxious to get down the country and eventually, in November 1920, persuaded Stack to allow them go. No communication was possible between the Ministry and the Court Registrars by that time, so all arrangements would have to be made in situ and be liable to change at the last moment to avoid arrest. Crowley went to the West and was arrested within weeks: he was sentenced to two years’ hard labour by a court martial. Davitt, although he had many close encounters, not only managed to slip through the military net, but to hold makeshift courts in at least five counties all during the ‘Terror’, as the period between October 1920 and March 1921 is referred to in correspondence.

The Truce

By the following June, communication was resumed with headquarters and the Minister was demanding reports and returns from all theRegisters for the previous eight months! He was determined that during the period of the Truce, the courts would become so entrenched that no matter the outcome of any talks, the structures would be strong enough to survive-hence his rallying call to the Registrars. He judged the situation rightly: although there were several confrontations with the RIC and an angry rebuke from Lloyd George to Griffith and Collins on the first day of the London Conference, the Dail Courts took on a tremendous amount of new business, especially from commercial companies and local authorities. This growth was threatened by the Treaty, and particularly by the proclamation of 16 January 1922 which stated that the law courts and all public bodies formerly under the authority of the British Government were to continue in operation until the establishment of the Irish Free State.

Scene of the devastation caused by the

burning of Cork City 11 December

1920. (CORK EXAMINER)

The Treaty

There was consternation and a clamour that the Dail Courts should not be abandoned. Reassurance was immediately to hand. George Nicholls TD, a solicitor from Galway, was given the sole task of supervising the courts as an assistant minister in the Provisional Government. He wrote to the protesting registrars and justices: As the Republic and the Republican Government still stands, orders and instructions issued by the Provisional Government have no influence in any way on Republican Court officials. The Republican Courts shall continue to function as heretofore and all necessary steps must be taken to boycott the Enemy Courts until the Irish people approve of the Free State Government. Our position remains unchanged and the Republican Courts are the only legal courts of the Irish people. Around the time of this strange advice, the same junior minister considered whether he should prepare the commissions for His Majesty’s Judges to be sent on the Winter Assizes! After consideration over several days they were not permitted to go, probably because it proved impossible to remove from the wording of the commission the status of the King vis-a-vis his Irish subjects.

Take-over

Take-overSo the Dail Courts continued to prosper at the expense of those which alone were recognised under the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. Outside of Dublin most serious crimes were tried before a Dail Circuit Judge sitting with a jury. Convicted prisoners served their sentences in the state gaols. The Republican Police had a brigade in each area, attended at the courts and executed their warrants and judgements, although there were ample grounds for complaint in the haphazard fashion in which the latter duties were carried out. The Royal Irish Constabulary was being stood down and the formation of the Garda Siochana was bogged down in continuing controversy. Debtors frequently sought injunctions to stop plaintiffs suing them in the established courts, whose orders sheriffs were slow to execute in any case. Resident Magistrates and their clerks protested to the Chief Secretary’s Office that their courthouses had been taken over by the Parish Courts, but nothing was done about it and they finally gave up.

Confusion

The matter of the dual jurisdiction did not trouble the government unduly: when it was raised in cabinet discussion was deferred. However, a memorandum was prepared-probably by Hugh Kennedy, the Law Adviser-that the High and County Courts should be given back the work that had been taken from them by the Dail Supreme and Circuit Courts and that lawyers should replace the Resident Magistrates in reformed Petty Sessions. Although the drafting of the Free State Constitution had been completed, it was not suggested that a committee should begin immediately to plan for the new courts to be established under it. Such a move would, at least, have given the impression that something was being done to sort out the muddle. The drift continued until 23 June 1922 when the Law Adviser was instructed to prepare commissions for the Summer Assizes, although there was no hint of what cases were to be heard, nor from what venues accused persons could be returned for trial. The unspoken questions remained unanswered because five days later the Civil War broke out. On 13 July 1922, the Assistant Minister, purporting to act under a decision of the ‘Dail Eireann Cabinet’ suspended the sitting of the Supreme Court and ordered the immediate return of the judges from their circuits. When George Plunkett, a Republican prisoner, obtained a conditional order of Habeas Corpus from Judge Crowley, the government, on 25 July, hastily rescinded the decree of 29 June 1920 which had created the Dail Courts, leaving only the Parish and District Courts outside of Dublin in place until some alternative form of summary justice was devised.

British troops outside Mountjoy Jail.

(JOSEPH CASHMAN)

Abolition

The reaction that greeted the proclamation of the previous January was revived in the astonished protests, resolutions of county coun- 36 HISTORY IRELAND Autumn 1994 cils and letters to the papers. It later became clear that the Provisional Government and its advisers had no appreciation of the extent or nature of the work carried on in the courts, nor the chaos that would follow from the unheralded suppression. Although the official statement laid heavy emphasis on the immediate availability of an alternative legal system which was now under native rule and paid for by the taxpayer, it was not in a state of readiness, partly because the goal-posts had been moved. There were no courts to which offenders could be sent for trial, nor juries willing to serve. The County Courts had practically ground to a halt and there was no possibility that the Assize Judges could travel while civil war raged. The transition was easier in Dublin where there truly was an entire hierarchy of courts in working order. Sir James Molony, the Lord Chief Justice wrote to Hugh Kennedy on 15 July 1922-a full week before the rescinding of the 1920 decree-anticipating that there would be a ‘considerable influx of business into these courts now that the Republican Courts had been brought to an end’; at the same time he conceded that the title ‘Rialtas Sealadach na hEireann’ would appear in future on the documents of the High Court. Almost two years would pass before Molony ceased to the Lord Chief Justice of Ireland, a title he jealously guarded in spite of the Government of Ireland Act 1920. The Resident Magistrates were pensioned off to be replaced by twenty-seven male lawyers in October, tactfully called ‘District Justices’. · At the same time, a committee was appointed under Lord Glenavy-a former Lord Chief Justice and Lord Chancellor, now Chairman of Seanad Eireann-to advise on the structures and form of the future constitutional courts. The resulting bill took more than eight months to pass through the Dail and Seanad. Winding-up It was in an impressive ceremony at Dublin Castle on 11 June 1924 that Hugh Kennedy, Chief Justice of the Irish Free State, administered the oath of office to his eight fellow judges. Four of them had held judicial office under the British but also included was Justice Meredith, formerly President of the Dail Supreme Court. He had sat for the last time that day as Chief Judicial Commissioner in the court of the Dail Eireann Courts Winding up Commission just across the way in the Upper Castle Yard. The latter had been established by statute in August 1923 to adjudicate and register more than five thousand Dail Court judgements left in the air when the courts were suppressed. The Commission was given extraordinary, though temporary, judiCial powers which were transferred to the High Court in 1925. This jurisdiction continued to be actively exercised well into the following decade. It has frequently been remarked that the legal system which emerged in independent Ireland was a mirror image of that in England: however, the Circuit and District Courts were modelled directly on those of Dail Eireann. Wigs and gowns and judicial titles were retained but many lawyers prominently associated with the seditious courts were appointed to the bench, mostly notably, Conor Maguire, Chief Justice, and Cahir Davitt, President of the High Court. In a judgement issued in January 1923 the Land Court had been declared an illegal and usurping tribunal: by 1925 its judgements were being upheld in the High Court by Justice Wylie, who had prosecuted at the court martial of the leaders of the 1916 Rising. The way it turned out was a fine example of an Irish solution to an Irish problem.

Mary Kotsonouris is a former District Court judge.

Further reading:

M. Kotsonouris, Retreat from Revolution (Dublin 1994).

Take-over

Take-over