Resurrecting an ancient chief

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Issue 5 (September/October), Volume 22

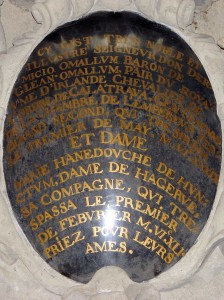

The Church (now Cathedral) of St Michael and St Gudula, Brussels, where Dermot O’Mallun, the last Irish-born chief of the O’Moloney sept, was interred in 1639.

Background to Dermot’s flight

An epitaph records his burial there. (Cathedral of St Michael and St Gudula)

It is clear, then, that neither Dermot nor those writing in his support in Europe were exaggerating when they claimed that his family had their lands confiscated in Ireland after having taken up arms against England, that many had also lost their lives and that he himself had been forced to flee at fifteen years of age.

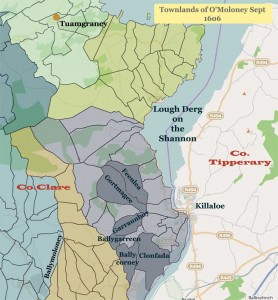

O’Moloney lands

O’Molony sept lands in County Clare c. 1600

Twenty-five years later, in 1631, by letter from Brussels, Dermot successfully renegotiated the return of the same O’Molony sept lands from Barnaby O’Brien, Donogh’s son—and in the English language too, a language in which, by his own admission, he had little skill. The correspondence indicates that the earl of Thomond himself was also a relative of Dermot’s, probably by virtue of his paternal grandmother, Margaritta O’Brien. The 1631 letter to Barnaby lists the lands that belonged to the sept and outlines the circumstances in which they had been transferred in 1606. Barnaby readily agreed to return the lands and, whilst noting that he was sure that his own father Donogh had dealt honourably with the O’Molonys back in 1606, he stipulated a price of £800 for their return. A legal contract transferring all the lands to Dermot for a price of £2,000 as the ‘head and supreme of their sept’ was drawn up by ten members of the O’Molony sept. (It is not clear why the contract price was more than Barnaby O’Brien’s original asking price.)

Married into Flemish nobility

By the time Dermot renegotiated the land transactions with Barnaby in 1631, however, he had already gained much experience on the Continent in law and other matters. After his escape to Flanders, he enrolled in law in the University of Douai, where he studied for twelve years. In Douai he encountered Marie ‘Dite De Hunctun’ de Hannedouche, dame de Haguerne, daughter of Sebastien Hannedouche, seigneur de La Haye, and they married around 1610. The Hannedouches were one of the many noble families of Flanders; Dermot, Hugh Albert O’Donnell, Thomas Preston and others ‘found brides in the Netherlands nobility’. His father-in-law was a man of standing in Flanders and with his support Dermot applied for legal positions in Douai and the surrounding towns. Several correspondences to the Archduke Albert around the time are informative about Dermot’s Irish past. Sebastien wrote to Albert in support of Dermot on 6 March 1611, while the archbishop of Cashel, Dave Kearney, similarly wrote on 16 March and Christopher Cusack on 20 March. These letters show that Dermot’s family possessions in Ireland had been confiscated and that he had come to Flanders over twenty years previously. He had already been in the archduke’s employment for twenty years by the year of these letters, was a licentiate in law and was of such standing and character that he was suitable for any position for which the archduke might consider him. Furthermore, the letters confirm that the archbishop of Killaloe, Cornelius Mulryan, was his uncle.

Order of Calatrava

To further consolidate their positions as persons of entitlement, many Irishmen—including Dermot O’Sullivan Beare, Hugh O’Donnell, Hugh O’Neill and Dermot himself—applied for admittance to the Order of Calatrava, a military order of Spain. Admittance to one of these orders was not trivial; applicants were required to prove their suitability and to provide their genealogical credentials. The documents had to be submitted to an examining commission and the admission process could be lengthy. Dermot, however, was admitted in 1616, being sponsored by Donnacha O’Cleary, amongst others. His admission documents are still held in the Archivo Histórico Nacional in Madrid and clearly show his descent from other Irish sept leaders, including Torlough O’Brien, John McNamara and Daniel O’Mulrian.

With a membership of the Knights of Calatrava under his belt, Dermot soon found favour with King James of England, who, by letters patent on 5 October 1622, created him ‘Baron of Glenomallun and Courchy’ for life, with remainder to his son, Albert O’Mallun, and ‘heirs male of his body’. The Infanta Isabella (Archduke Albert’s wife) also used her influence in this regard. ‘Courchy’, however, is almost certainly a misprint or translation error in various documents and should be Quinche or Quinchy, as it is in some documents, or as in old Irish—Cuinché. This is the modern parish of Quin or the ‘barony of Quincé’. Indeed, Dermot’s grandmother, Slany MacNamara, hailed from Knoppogue (Cnapóige in Irish) in Quin, which is probably the reason for its inclusion in the created title.

A series of correspondences between 1609 and 1631 reinforce for us Dermot’s position in Flanders at the time and his past in Ireland. From Douai he wrote to Archduke Albert on 12 August 1609 looking for the vacant post of bailiff of Douai and saying how he had to support two Irish students studying in the university. In a series of letters in 1618 (referred to by Margaret MacCurtain in Women in early modern Ireland), he wrote about how his loss of pension affected his ability to support his family and oversee his affairs. In 1621 he wrote to the pope seeking a recommendation to the king of Spain. In the same year Lucio Sanseverino, internuncio at Brussels, corresponded with Cardinal Borghese in favour of ‘Dermicius’. In that year also Dermot assisted at the funeral of Archduke Albert, who died on 13 July, and led the cheval de Jouste (one of several mounted guards of honour). On 24 February 1622 the Infanta Isabella wrote to Jehan de Pretz, treasurer of the Domains, ordering him to pay 200 florins, his yearly pension, to Dermot. On 4 September Count Gondomar corresponded with Isabella about Dermot. In October 1623 George Chaworth, writing to the duke of Buckingham looking for a favour, used Dermot as an example of one having ‘obtained a title of honour’ in Ireland through the influence of the Infanta. In July 1626 Isabella instructed Diego de Messia to further the pension case of Dermot Omalun with his majesty. On 30 March 1629 a grant of 200 crowns yearly, for a further three years, was given to Baron Omalun (Albert), son of Dermot, ‘lord and peer of the kingdom of Ireland, knight of the Order of Calatrava, and equerry to the Archduchess’. Again, on 29 May 1630 there are orders for the payment of 300 livres to Baron Gleanomalun. Finally, we see Dermot’s son Albert writing on 6 November 1631: ‘Albert Baron d’Omalun, godson of her Highness, son of the Baron of Gleanomalun and Guerchy, represents that although his Majesty, in consideration of the confiscation of his estates and baronies because his family had taken up arms against England . . .’—once again confirming the confiscation of Dermot’s estates in Ireland.

Conclusion

In conclusion, then, Dermot’s life can be summarised as follows: he was born in Ireland in the 1570s around the time of the Desmond rebellions, escaped to Flanders in the 1580s, was employed by Archduke Albert and Archduchess Isabella in the 1590s, studied law in the University of Douai in the 1600s, married into Flanders nobility in 1610 with subsequent issue, was admitted to the Knights of Calatrava in 1616, was created Baron Gleanomalun and Cuinché in 1622, regained the O’Molony lands in Clare in 1631 and finally died on 1 May 1639, with subsequent interment in Brussels. So it is possible to resurrect the life of a forgotten chief to an amazingly detailed degree, with patient research and investigation of historical resources, both in Ireland and abroad.

Gerry Moloney lectures in computing in the Institute of Technology, Carlow.

Read More: Family Life

What’s in a name?

THE COUNCIL OF IRISH CHIEFS AND CLANS OF IRELAND PRIZE IN HISTORY 2015

Further reading

B. Jennings (ed.), Wild Geese in Spanish Flanders, 1582–1700 (Dublin, 1964).