Restored to death? Skellig Michael’s World Heritage Status under threat

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Issue 3 (May/Jun 2007), News, Pre-Norman History, Volume 15

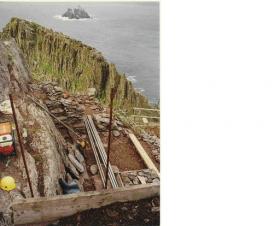

The South Peak oratory immediately after archaeological excavation

Skellig Michael is one of only two World Heritage Sites (WHS) in the Republic. It comprises the main monastic complex and the much smaller South Peak hermitage complex. Controversy has long dogged the Skelligs. A joint Irish–Welsh expedition raised concerns about damage caused by conservation work in the 1890s. There were controversies over the illegal dumping of spoil, the use of dangerous pesticides and unease over the scale of rebuilding when the main complex was conserved by the Office of Public Works (OPW)/Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government (DoEHLG) in the 1980s and 1990s.

Almost all of the key elements of the monastic complex have now been ‘conserved’ or restored. Nineteenth-century layers and structural elements were removed, reflecting an architectural response to conservation. These included unstable retaining walls but also modifications to the entrances and the structure of some of the cells. In the main oratory an altar, used by pilgrims into the 1930s, was removed on the grounds that it supposedly dated from the nineteenth century. This is contrary to a range of International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) charters; it is also sacrilege. A University College Cork MA thesis on heritage management on the Skelligs concluded in 2000 that the damage was being inflicted by the OPW rather than by tourists; it described a reconstructed monastic toilet as a ‘work of fiction’; it noted that the intact small oratory has been virtually rebuilt; and it criticised the layout as a work of imagination rather than being based on any surviving evidence.

Work is ongoing on the South Peak. Sadly, there is extensive evidence that much of this work has not reached modern standards. Nineteenth-century work practices persist and excavation is followed by ‘instant reconstruction’. The stonemasons work on site without direct archaeological supervision (‘unencumbered’) for much of the time (although their work is later inspected). As a result, original features have been destroyed (see photographs), and original terrace walls are reconstructed (according to the OPW/DoEHLG) ‘on the original line of the wall being repaired’. But rebuilding a wall along its original line is archaeologically meaningless; at best it can produce a reasonable facsimile of the original. The potential value of Skellig Michael for future researchers is being destroyed. Genuine archaeological remains have been replaced by faux-monastic twenty-first-century imitations.

The management team itself lacks key figures for a restoration programme of this type, notably a soil scientist, a remote-sensing specialist, an architectural historian or a

after ‘instant reconstruction’ ‘unencumbered’ by archaeologists.

medieval historian. No conservation reports or archaeological assessments are publicly available on the work so far. Without them it is impossible to make an informed evaluation of the work and its impact on the surviving remains.

Skellig Michael has been proposed as a Special Protection Area and is a nature reserve. Nevertheless, no environmental impact assessment (EIA) was carried out prior to work on the South Peak, breaching the European Union habitat directive. In 2004 concerns were raised at the Heritage Council but were overruled. According to the management team, ‘ministerial consent under the National Monuments Act’ constitutes sufficient legal authority. In addition, a single official from the National Parks and Wildlife Service assessed the work’s impact on local birdlife. This is clearly inadequate, and it is chastening to consider that no other potential impacts, immediate or downstream, were assessed at all.

The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention require a detailed management plan for each World Heritage Site. This should direct the work, allow for detailed assessment of each stage and guarantee that the authenticity of the site is not compromised. A 2002 Antiquity article refers to such a plan for Skellig Michael, but when queried by journalists the management team conceded that it does not exist. A provisional management strategy was sent to UNESCO in 1996 but this is woefully incomplete and does not reach the standards of similar plans elsewhere. Appendix 8 has one paragraph on guides, three on visitor management and boats, two on monitoring, and the following on the South Peak:

‘The fragile hermitage on the South Peak is being constantly monitored. Because of the difficult climb, very few people ever bother to go there. Numbers have increased slightly in recent years and it may be necessary to close off this area altogether until such time as conservation work has been undertaken to all the man-made structures.’

The conservation work is not described. The OPW/DoEHLG claim that an updated management strategy was sent to UNESCO in 2005, but enquiries by the author and by Village magazine revealed that requests for information from UNESCO remain unanswered. This could lead to the delisting of the Skelligs, which would reduce the chances of any other potential World Heritage Sites in Ireland.

The official response to public concern about the Skelligs has been quite disturbing. Minister Tom Parlon gave inaccurate assurances that the work undertaken was the absolute minimum necessary. Claims that the remains on the South Peak were about to fall into the sea were never substantiated. Without engineering or technical studies we cannot tell whether the present works are necessary or massively excessive.

The intact small oratory has been virtually rebuilt, while a reconstructed monastic toilet to the left of it has been described as a ‘work of fiction’.

The heritage bodies also failed to act. The Heritage Council failed to call for an EIA. After complaints it organised two site visits, both by lone archaeologists without the necessary documentation. No effort was made on either occasion to hear the opinions of anybody not connected with the DoEHLG/OPW. Members of Birdwatch Ireland have expressed serious concerns about the effect (denied but not studied) on local birdlife, and photographic evidence of questionable work practices has emerged in the press. The Institute of Archaeologists of Ireland has repeatedly called for full publication of the current management data and for evidence that UNESCO authorised the recent work.

Cultural resource management has moved on since the 1980s. The standard of care required for World Heritage Sites is that of international best practice, but this appears to have passed Skellig Michael by. As a result, millions may have been spent and irreversible damage done without any proof that it was necessary or any consideration of alternatives. The work on the Skelligs must be halted immediately and the alleged damage investigated. A full and open debate is needed, ‘unencumbered’ by the traditional reluctance of the academic and professional world to delve too deeply into the work practices of the heritage authorities.

Michael Gibbons is a member of the Institute of Irish Archaeologists and a former coordinator of the OPW’s Sites and Monuments Records Office.