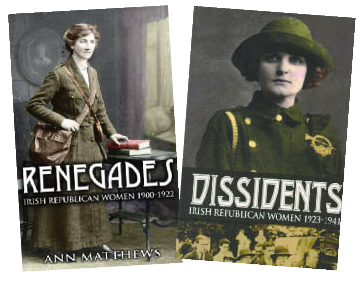

Renegades: Irish republican women | Dissidents: Irish republican women

Published in Featured-Book-Review, Issue 1 (January/February 2014), Reviews, Volume 22Renegades: Irish republican women 1900–1922

Ann Matthews

(Mercier Press, €19.99)

ISBN 9781856356848

Dissidents: Irish republican women 1923–1941

Ann Matthews

(Mercier Press, €18.99)

ISBN 9781856359955

These two volumes, based on research undertaken by Ann Mathews for her Ph.D, look at the trajectory of Irish women’s involvement in republicanism, both militarily and politically, from the early 1900s, ending in 1941. They give the reader a chronological narrative of the extremely complex nature of female activism in these four decades of the twentieth century. Mathews details the many organisations that women set up, joined or worked in concert with; she is excellent on the interrelationship between the many nationalist female organisations such as Cumann na mBan and their sometimes cooperative, sometimes fraught, but always complex relationships with other organisations. In particular, Mathews demonstrates the often tense relationship between the women’s organisations and their male counterparts in Sinn Féin, the Irish Volunteers, the IRA and later Fianna Fáil; she notes that ‘in founding Fianna Fáil, de Valera was freed from the pressure of having to consult with the women on any topic’ (Dissidents, p. 189). As Mathews demonstrates, women’s relationships with male-run organisations, such as the Irish Volunteers, were often not accepted or desired by the men. Even where the women were allowed membership it was often on a less than equal basis. One of the author’s stated aims was to refocus discussion on women’s involvement in Irish republicanism from the promotion of the small number of ‘iconic’ figures like Maud Gonne MacBride and Countess Markievicz to detailing the work and activities of the numerous other women involved. She does note the names and activism of dozens of women—some already known, some unknown—and allows the reader to get a detailed understanding of the extent of female involvement in public politics and militancy of the early twentieth century, most particularly in 1912–23. In Renegades she focuses on the involvement and work of women like Helena Molony, Jennie Wyse-Power, Kathleen Lynn, Kathleen Clarke and Mary MacSwiney. In Dissidents, as well as MacSwiney, Wyse-Power etc., the work of other, lesser-known women like Eithne Coyne, Áine Ceannt, Margaret Buckley, Sighle Humphreys, Sighle Bowen and Maire Comerford, among others, take centre stage and deservedly so.

Nevertheless, in her laudable effort to undermine the dominant iconography of Markievicz and Gonne MacBride in Irish women’s historiography and get to the histories of the numerous other women involved, Mathews allows the two women to dominate large portions of both volumes. Again and again she comes back to ‘slay’ these iconic ‘dragons’ and in doing so creates mostly negative, one-dimensional images of both women. Gonne McBride was a self-seeking fraud, according to Mathews, who ‘staked a claim to be Ireland’s Joan of Arc’ (Renegades, p. 37). We also have here the usual stories about Markievicz: the bad mother, the coward who ran away during the Civil War and had ‘hidden in Scotland’ (Dissidents, p. 132). Like Gonne MacBride, Markievicz, who has been treated of in at least six biographies to date, is a woman whose life and activism are much contested and vigorously debated. From her bibliography it is obvious that Mathews has read these biographies, yet we see no discussion on the differing views on Markievicz; instead we are presented with one, seemingly uncontested, ‘truth’ of her life, activities and motivations. Such one-dimensional presentations of these women at leadership level detract from the meticulous primary source research evident in this work. While Gonne MacBride and Markievicz were often, it is true, self-seeking, difficult and demanding, they were also women who put in the hard work, who were dedicated to ideals and who sacrificed a lot for what they believed in. They deserve more nuanced, rounded, balanced analyses of their lives, work, activism and personalities.

In her sections on the activities of Cumann na mBan during the War of Independence, the Treaty debates and the subsequent Civil War, Mathews constructs narratives of an often traumatic history. Although she insists that the ‘war on women’ ‘has never been discussed previously in a historical context’ (Renegades, p. 267), as early as 1969 Lil Conlon in Cumann na mBan and the Women of Ireland was writing that ‘the going was tough on the female sex . . . swoops were made at night, entries were forced into their homes . . . the women’s hair was cut off in brutal fashion as well as suffering other indignities’ (Conlon, p. 224), while Kathleen Clarke, among some others, discussed the violence of night-time raids by the Black and Tans in their memoirs. Nevertheless, sexual violence, committed by both sides, during the War of Independence is an issue with which historians are only recently coming to grips and Mathews rightly brings it to the fore. She also looks closely at the oft-stated ‘fact’ that the majority of Cumann na mBan were anti-Treaty and presents a much more complex picture. She writes that intransigence on the part of Cumann na mBan anti-Treaty women after 1923 left them behind ‘in the political wilderness’ (Dissidents, p. 256). While this is true, it is certainly not the sole reason why Irish women continued to be, for the most part, outside the political power structures of the Irish state for many decades.

In these two volumes Mathews, drawing on archival research, weaves a solid, detailed, if under-analysed and sometimes one-dimensional, narrative of Irish women’s involvement in political and militant republicanism. HI

Mary McAuliffe lectures in Women’s Studies at University College Dublin and is president of the Women’s History Association of Ireland (WHAI).