Remembering Larkin and the dock strike of 1907

Published in 1913, 20th Century Social Perspectives, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 4 (July-August 2013), Volume 21

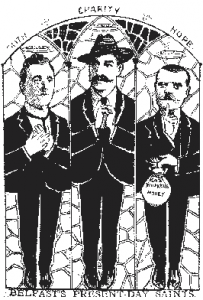

‘Faith, Charity and Hope’—cartoon depicting, respectively, William Walker, James Larkin and Alex Boyd. (Nomad’s Weekly, 17 August 1907)

The Belfast dock strike of 1907 marked James Larkin’s arrival and first extraordinary impact in Ireland. It revealed that Belfast alongside a British economy had a very Irish one that governed the conditions of the unskilled. It marked the first substantial organisation of the unskilled in the city. Although relatively small-scale as a strike, it involved mass working-class engagement across the community divide. Combined with an indirectly related police mutiny, it led to an unprecedented crisis and massive use of the army to smash both the mutiny and the strike.

A defeat

Idealising the 1907 dock strike loses sight of the fact that in large measure it was a defeat, and one that bore particularly heavily on the original participants, Protestant cross-channel dockers. That opened the way for sectarian allegations about the conduct of the strike. The fragile alliances across the political divide that had supported the strike movement proved just that. Joe Devlin and the Dungannon Clubs, precursors of Sinn Féin, were far more interested in the police mutiny and the military intervention than in the strike movement, and disowned Larkin. So too did Tom Sloan, Independent Orange MP for South Belfast, ever a weather-vane of opportunism within that constituency. Others held firm but suffered the consequences. Lindsay Crawford was sacked as grand master of the Independent Orange Order and from his job as editor of the Liberal Ulster Guardian. That other key Independent Orangeman and organiser of the municipal employees Alex Boyd lost his council seat in 1908. He was not alone. The labour movement did not disown Larkin; it sought to retire to the safe ground of conventional Independent Labour Party politics, but lost all its seats. When in 1911 William Walker defended the ‘municipal socialism’ of Belfast he was lauding a corporation devoid of labour representatives.

Labour divisions and Unionist intrigue

Larkinism meanwhile proved unstoppable elsewhere. His message to the unskilled in Newry, Dublin or Cork proved as intoxicating as it had originally been in Belfast. Strained relations with James Sexton, leader of the National Union of Dock Labourers (NUDL), and with British trade unions evident in Belfast led to an inevitable break and the formation of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union in January 1909. Larkin’s hastily adopted new persona as a specifically Irish militant certainly added to Belfast difficulties. Alex Boyd’s defection and leading wrecking role on behalf of the rump of the NUDL helped to ensure that neither union was effective on the docks by 1910. Yet the labour movement and its allies were already imploding by late 1908 and before the formation of the ITGWU.

One can focus on labour divisions but the crucial role in subsequent events was played by militant unionism. Correspondence from 1909–14 between a spy, Edward Bradshaw, and James Davidson, assistant deputy grand secretary of the Orange Order, gives a rare insight into what was afoot. Bradshaw attended the executive committee meeting of the North Belfast Unionist Association in December 1909 and asked ‘Whose fault was it that there were 2,000 socialists in North Belfast? I said it was the Protestant employers . . . and if the employers would start and weed them out, and give employment to the Protestants and Orangemen . . . you would have these men to work and vote for you . . .’

Bradshaw was delighted when Mr Clark and Mr Thompson ‘wanted to know if I could give more information’. George Clark, who had narrowly defeated William Walker in a 1906 by-election contest for the North Belfast seat, was an owner of Workman and Clark’s shipyard. Thompson was elected in Clark’s place in 1910. Later Bradshaw reported that Unionists in East Belfast ‘had since the same question up’. These discussions were taking place well before the crisis of 1912 over the third Home Rule bill and the signing of the Ulster Covenant, the centenary of which was celebrated in partisan fashion last year. A centenary that has not been marked is the directly connected wave of workplace expulsions in July of that year. Unsurprisingly, these commenced in the Workman and Clark shipyard and only then spread to Harland and Wolff, where Lord Pirrie was hostile to any such endeavour.

Some 3,000 workers were expelled and 600 of these were Protestants, a significant proportion of the 2,000 socialists targeted by Edward Bradshaw in 1909. While Catholics were inevitable targets, for Unionists the elimination of dissent within the Protestant community was at least as important.

James Connolly

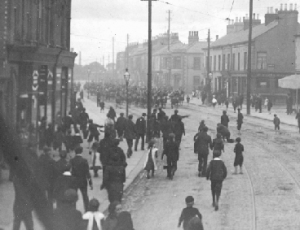

Picketers throw stones at Cameron Highlanders as they advance up the Grosvenor Road, Belfast, August 1907. (Alex R. Hogg)

James Connolly as Belfast organiser of the ITGWU from 1911 found it difficult to penetrate beyond the Catholic community. He angrily pointed out to Larkin that the Irish orientation of the union limited possibilities, yet in the period up to 1914 no other union made a significant impact with the Belfast unskilled. Belfast Trades Council could offer sympathy to the Dublin strikers of 1913 but no more. Their message came from a city in which they had been driven from the public arena and their former platform on the Customs House steps. Connolly sought to maintain a public presence but, significantly, from the new venue of the Central Library steps in Royal Avenue, from where immediate retreat into the Catholic ghetto behind the library was possible. At the last meeting before even this venue was abandoned Connolly famously warned that partition would lead to ‘a carnival of reaction’. It was already under way!

Decade of centenaries and ‘shared history’

We must now approach the conundrum of how the Belfast strike of 1907 can fit into the ‘decade of centenaries’. Can it be done, even if it falls outside the chosen years of 1912–22? Why, indeed, is the attempt being made?

Thomas Johnston, a participant in 1907 and later leader of the Irish Labour Party, provided a justification for looking back when he argued that the events of the entire period ‘can be connected directly with the strikes on the docks in Belfast in 1907 and the military intervention at that time’. That continuity is plausible in a southern context, though by the time Johnston commented notions of a revolutionary leadership role for labour in the new Ireland had vanished. Nonetheless, the labour movement had played a not insignificant role in the national revolution, even if its reward was to be merely a bit player in the emergent deeply conservative state.

By contrast, for the labour movement in the north there was no similar continuity; it was eviscerated. Following the debacle of 1912–14, wartime saw some revival in its fortunes. The engineering strike of 1919, though pursued in a purely sectional interest, has claims to be Belfast’s only general strike. Right up to 1920 the advance was maintained and no less than twelve Labour councillors were elected in Belfast.

All too easily, however, the wheel turned full circle in the final act of Unionist state formation, and in July 1922 workplace expulsions were used on a massive scale both against Catholics and Protestant radicals. Those Labour councillors no longer dared attend City Hall meetings. Accordingly, inclusion now of the events of 1907 in northern commemorations of the decade of centenaries serves only as a fig-leaf for the ugly reality of the subsequent fate of the labour movement. More generally, historians who have been enlisted to portray the decade as one of ‘shared history’ do a disservice to their profession.

The recent intimidation of Alliance Party representatives in the Union flags controversy, although a pale shadow of the past, serves as a reminder of the once potent forces that eliminated all opposition in the emerging Unionist state. HI

John Gray is former Librarian of the Linen Hall Library, Belfast.

Read More : 1907 Belfast dock strike time-line

Further reading

J. Gray, City in revolt: James Larkin and the Belfast dock strike of 1907 (Belfast, 1985).