Recycling the dustbin of Irish history: the radical challenge of ‘folk memory’

Published in 18th-19th Century Social Perspectives, 18th–19th - Century History, 20th Century Social Perspectives, 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 1 (Jan/Feb 2006), Volume 14

Seosamh Ó Dálaigh (left) recording Cáit and Máire Ruiséal of Dún Chaoin, Co. Kerry, c. 1942. Equipped with ediphones (wax-coated cylinder phonographs), full-time folklore-collectors of the Irish Folklore Commission made repeated visits to exceptional informants. (Department of Irish Folklore, UCD)

‘At Lincoln Cathedral there is a beautiful painted window, which was made by an apprentice out of the pieces of glass which had been rejected by his master.’ With this parable the budding English historian Thomas Babington Macaulay illustrated the central argument of his 1828 debut essay ‘History’, which advocated that historical scholarship could benefit from the inspiration offered by historical fiction. The professionalisation of Irish history was grounded in the debunking of popular ‘mythology’ (as made clear, for example, in T.W. Moody’s seminal essay ‘Irish history and Irish mythology’). Accordingly, ‘a continuous compulsion to confront myth and mythology’ has been identified by Ronan Fanning as ‘a striking characteristic of modern Irish historiography’, and Michael Laffan contrasted the study of Irish history with the ‘accumulation of folklore’.

For all its noteworthy achievements, adherence to this positivist creed has resulted in the astounding paradox that historians of modern Ireland have mostly opted to overlook oral traditions, even though the Ireland that they describe was renowned for its rich oral culture. By and large, folklore has been consigned to the dustbin of Irish history (with the notable exception of ground-breaking work on oral traditions of the Great Famine). Whereas professional practitioners of the historian’s craft have contemptuously discarded vernacular source materials (both written and oral), it is worth contemplating some of the ways in which this ‘refuse’ was creatively utilised outside the halls of academia.

However, the initial problem one encounters upon setting out to rummage in the dustbin of history is the overwhelming quantity and the incredible variety of information available to the researcher. Not only is there a voluminous body of sources that needs to be sifted through, but also—since the material does not conform to the familiar standards of state archival documents—questions can immediately be raised concerning methodology. For their part, folklorists have shown a preference for epic tales and did not develop a coherent methodology for the study of Irish folk history. Is it at all possible to ‘historicise’ folklore accounts, and how can the discipline of history benefit from such an exercise? With this concern in mind, rather than engaging in purely theoretical ruminations, it is instructive to consider a case-study and tease out its larger implications for Irish historiography, taking into account that a cursory discussion on this neglected topic will inevitably be preliminary and partial.

A ‘hidden Ireland’

Séamus Ennis taking notes from one of his most prolific informants, Colm Ó Caodháin. Ennis worked as a full-time collector for the Irish Folklore Commission from 1942 until 1947 and concentrated on traditional music and songs. (Department of Irish Folklore, UCD)

While Georges Denis Zimmerman convincingly demonstrated the value of political street ballads as ‘a running commentary on Irish political life seen “from below”’, little, if any, historical importance has been attributed to other popular singing genres, such as children’s songs. Yet, as Iona and Peter Opie showed in their classic study on The lore and language of schoolchildren (1959), historical knowledge was inadvertently imparted in children’s rhymes. Fans of the popular music group Clannad may recall the song ‘Mise agus Tusa’ on their Cran Úll album (Tara Records, 1980), which opens with the verse:

An raibh tú i gCill Ala’

Nó i gCaisleán an Bharraigh,

Nó an bhfaca tú an campa

a bhí aige na Francaigh?

(Were you in Killala

or in Castlebar,

Did you see the camp

of the French?)

This song, which the band learned in their native Gaeltacht of Gaoth Dobhair from a woman named Síle Mhicí, was a common children’s tune in Donegal and Mayo. Another song, described in the 1930s as ‘popular in the South’, included the verse: ‘Be a good boy and I’ll buy you a book / And I’ll send you to school at Ballinamuck’. The folklorist Bairbre Ní Fhloinn recalled how in her childhood her aunt in County Roscommon would recite a similar couplet while rapping her knuckles to the beat on the table: ‘Anthony Duck, Anthony Duck / Follow the Leader to Ballinamuck’.

In recent years, stylised Gaelic poetry has been the subject of eye-opening studies of such topics as early modern responses to colonisation and eighteenth-century Jacobitism, yet scant attention has been paid to historical references in more spontaneous forms of folk poetry. For example, a women’s repertoire of extempore singing composition during communal spinning sessions (which is reminiscent of the Scottish waulking tradition) includes the popular love song ‘Is óra a mhíle grá’. A version collected in the village of Devlin in Erris, north-west County Mayo, featured the verse: Níor fhág aon bhean óg Deibhleán / Ó bhí na Francaigh i mBéal an Átha’ (‘No young woman left Devlin since the French were in Ballina’). Evidently, various references in folk poetry and singing obliquely called attention to sites associated with the French invasion of the west of Ireland in 1798.

Right: A Celtic cross carved from the timber of Fr Conroy’s hanging tree, which was a site of folk memory in Castlebar until it was uprooted by a storm in 1918. Such commemorative crosses were recognised locally as relics of 1798.

Corresponding testimony can be found in idiomatic expressions of speech. In his pioneering study of Hiberno-English (published in 1910), Patrick Weston Joyce noted that ‘In and around Ballina in Mayo, a great strong fellow is called an allay-foozee, which represents the sound of the French Allez-fusil (musket or musketry forward), preserving the memory of the landing of the French at Killala (near Ballina) in 1798’. The novelist Séamus Ó Grianna (‘Máire’) observed that several French expressions had filtered into local parlance in his native Gaeltacht area in Ranafast, Co. Donegal, such as ‘cail úr a’ tsíl’, used to ask the time (quelle heure est-il), or ‘sláime tae geal’, used as an expression of indifference (cela m’est égal). It was believed locally that this linguistic curiosity could be traced back to a local carpenter who at the time of the 1798 rebellion had served as an apprentice in Westport and picked up some French in the company of the invading troops. Further study reveals that such examples are just the tip of an iceberg of a hitherto unstudied ‘hidden Ireland’.

The Year of the French

In practice, the French invasion of 1798 lasted a mere month. The small expeditionary force under General Jean Joseph Amable Humbert disembarked by the Mayo fishing village of Kilcummin on 22 August and occupied the small diocesan town of Killala that same evening. Following the taking of the market town of Ballina the next day, thousands of locals flocked to join the rebel cause. The self-styled ‘Army of Ireland’ went on to defeat a superior force and take possession of Mayo’s principal town in the famous ‘Races of Castlebar’ on 27 August, after which a ‘Republic of Connacht’ was proclaimed. Since expected French reinforcements failed to arrive promptly, the Franco-Irish army headed north along Mayo and into south Sligo, where their advance was checked by the Limerick Militia outside Collooney. They then embarked on a daring but ill-fated campaign across Leitrim and into north Longford, and were ultimately defeated on 8 September near the village of Ballinamuck, where the French received comfortable terms of surrender but shamelessly deserted their Irish allies to be massacred without discrimination. A fortnight later, on 23 September, the remaining rebel garrison in Killala met a similar fate, as the surrendering French were again spared but the Irish insurgents received no quarter, with a militiaman noting that ‘such terrible slaughter as took place is impossible for me to describe’.

This military narrative is familiar and, despite recent widespread interest in what has come to be known as ‘the Great Irish Rebellion of 1798’, little has been added in the past 70 years to our knowledge of the rebellion in Connacht and the north midlands. Based on documents found in archives in Dublin, London and Paris and on published contemporary accounts by eyewitnesses (none of whom, incidentally, spoke Irish and so had little idea of how the events were perceived by many of the locals), this may seem to be a straightforward story of limited historical significance. Indeed, it has been framed as a trivial affair in the grand meta-narratives of modern Ireland, so that consequently, in the words of Roy Foster, ‘the strange episode of the Republic of Connacht is a footnote to Irish history’. As such, this is a ‘footnote’ to a history that has been predominantly preoccupied with high politics, as perceived from Dublin and across the Irish Sea, and has had little time for popular non-metropolitan perspectives.

In contrast, hundreds of unstudied folklore sources testify to the centrality of the 1798 experience in provincial social memory. These were primarily documented by the fieldworkers of the Irish Folklore Commission (established in 1935), by pupils who participated in a highly successful folklore-collecting scheme (which the commission directed during the 1937–8 school year in conjunction with the Department of Education and the Irish National Teachers’ Organisation), and by the maverick historian Richard Hayes,

1798 monument on ‘French Hill’ outside Castlebar, Co. Mayo, erected in 1876 on the site of a grave identified in oral tradition and confirmed by excavation

who supplemented the archival research for his book The last invasion of Ireland (1937) with oral traditions that he collected from local people along the route of the Franco-Irish army’s campaign. Numerous additional folklore accounts have been collected from the time of the immediate aftermath of the events until the present day and are scattered throughout such miscellaneous sources as political pamphlets, social reports and geographical surveys, popular history books, antiquarian writing, travel literature, local histories, newspaper and journal articles, song books, historical fiction, commemorative paraphernalia, exhibition catalogues, personal papers and, more recently, in radio and television programmes, and even over the internet. Folklore accounts were collected not only in the four counties through which the Franco-Irish army campaigned (Mayo, Sligo, Leitrim and Longford) but also in the other counties of Connacht (Galway and Roscommon), down into parts of Munster (particularly Clare), up into areas of Ulster (Donegal, Monaghan, Cavan and Fermanagh), and from the north midlands into areas of Leinster (especially Westmeath). Far from being an inconsequential and parochial footnote, it turns out that communities throughout a quarter (if not a third) of the island emphasised the importance of this episode in their accounts of history. Overall, this record of ‘collected memory’ reveals that Bliain na bhFrancach, as it was named in Irish, or ‘the Year of the French’, was a major landmark in regional historical consciousness and was even considered locally to be the most significant event prior to the Great Famine.

The writings of the Castlebar schoolteacher and novelist Mathew Archdeacon show that references to the ‘time o’ the Frinch’ were prevalent already shortly after the rebellion. In his 1832 travelogue Wild sports of the west, William Hamilton Maxwell observed that ‘the landing of the French is a common epoch among the inhabitants of Ballycroy. Ask a peasant his age, and he will probably tell you, “he was born two or three years before or after the French”.’ This form of local calendar, through which ages and dates were calculated with reference to ‘the Year of the French’, persisted well into the twentieth century. In 1946 a folklore-collector described a 90-year-old female storyteller in Erris:

‘She, it was, who could tell the stories and she delighted in telling them. She was born shortly after the year of the French landing in Killala and it was most interesting to hear her tales as she heard them from people who were eyewitnesses of the invasion—the ships coming into Kilcummin Bay, the march of the French army into Killala and on to Ballina, men who went from Erris to join up with the French forces, and such incidents of that memorable year in Irish history.’

Though born some 60 years after 1798, she was hailed as a living link with the period, presumably because she had grown up at a time when there were still people alive who had participated in the events.

Remembrance in the village

Even though stories regularly change with each telling, folklore sources can sometimes surprise by unveiling information that was preserved intact and transmitted accurately over time. A striking example can be found in the case of the memory of a seditious toast (which suggests, given the popularity of political toasts in Ireland, yet another promising field of inquiry waiting to be studied).

A five-franc coin minted in Year 6 of the French Republic (1798) and inscribed ‘Union et Force’, which was found in a grave on French Hill outside Castlebar in 1876.

An informer’s letter to the lord lieutenant, written shortly after the rebellion, reported that a man in Oranmore, Co. Galway, ‘has been taken up for drinking the toast, That the King’s skin may be converted into boats for Bonaparte, which wish was inserted in a song that was sung in ale-houses and whiskey shops’. Over a century and a half later, in 1965, folklore-collectors recorded an 85-year-old man in a nearby area of County Clare performing a version of the popular folk song Ó, a bhean an tí that included the unusual verse: ‘Go bhfeicfimid Seoirse a chrochadh le corda / agus a chraicean mar bhróga ar Bhonaparte!’ (‘May we see George hanged by rope and his skin used to make boots for Bonaparte’). Not only would it appear that the original toast was recalled verbatim but it even identifies a possible error in the translated transcription of the archival document, which may have penned ‘boats’ instead of ‘boots’.

Notwithstanding such revelations, the primary value of folklore sources is not only what they can offer for a study of historical events but rather the interpretative insight they allow into how people throughout Ireland subsequently recalled their past. Around the time of the bicentenary of the rebellion in 1998, Irish historiography discovered a belated interest in collective memory. But most of the academic contributions were limited to a narrow consideration of select history books, inaugurations of monuments and the texts of speeches made at high-profile ceremonies and so did not fathom the grass-roots dynamics of social memory in provincial contexts. Such a superficial conceptualisation of memory has perpetuated a misleading thesis of ‘invention of tradition’ (pace the neo-Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm), whereby élites in the metropolitan centre supposedly dictated to masses in the periphery how the past should be remembered, though in practice this was seldom the case.

While they were not insulated from the influences of pageantry and rhetoric emanating from Dublin, local communities cultivated distinct practices of remembrance. All along the route of the Franco-Irish army, from Mayo to Longford, there were people in different localities who could point out ‘French roads’, where they believed the insurgents had passed through their neighbourhood. Place-names such as Baile an Champa (‘Place of the Camp’) near Killala, Camp Hill near Collooney, and Camp Field in south Leitrim mark the sites where the rebel army sojourned. Such micro-toponymy was generally not recognised in the official geography of Ordnance Survey maps.

Local historians Stephen Dunfort and Paddy Lavin identifying a Croppy’s grave in Maughan’s Field (named in memory of the dead insurgent) near Kilcummin, Co. Mayo. The site was recalled in local folklore and had been previously marked with a cairn.

Whereas historical scholarship confined its interests to the itinerary of the Franco-Irish army, the imaginary maps of ‘the Year of the French’ in social memory spanned a far wider range of demarcations that also included sites associated with popular agitation and local uprisings, routes Irish recruits took on their way to join the French, local skirmishes between smaller forces separated from the main body of the army, the flight of fugitives following the French surrender, pockets of continued insurgency and outlaw activities, and the punitive terror instigated by regular troops and yeomen in repressing the local population.

Social taboo ensured that the Frenchmen’s and Croppies’ graves, which littered the landscape of memory, remained untilled. Piles of stones (known as carn, leacht, meascán or clochan) were respectfully placed on many of these informal burial sites as an act of spontaneous com-memoration in accordance with traditional custom. On occasion, sites associated with the rebellion would be dug up in search of relics. An eye-opening case pertains to French Hill outside Castlebar, where in 1876 an ad hoc local committee set out to verify folk tradition and excavated the place where it was said that several French dragoons had died at the hands of Lord Roden’s cavalry. Subsequently, remains of corpses, allegedly still clothed in fading blue uniform (which crumbled once exposed to daylight and fresh air), were discovered, alongside brass buttons, a bayonet and three eighteenth-century French silver coins. A monument in the shape of an obelisk was then erected on the site, which became a locus for future provincial commemorations. Though historians have described the centenary celebrations of 1898 as a hotbed of political manipulations and a crucible of memory imposed from ‘above’, this act of public commemoration, which originated in local belief in oral tradition, anticipated centennial commemor-ation by over two decades.

A tree on the Mall in the centre of Castlebar was identified as the gallows on which the venerated Mayo rebel priest, Father Conroy of Addergoole, was hanged. After it was uprooted by a storm in 1918, Celtic crosses were made from the wood and preserved locally as treasured keepsakes. Their status as nationalist relics was publicly confirmed at a civic reception in 1924, when one of the commemorative crosses was presented to the visiting Irish-American dignitary John Devoy, and other revered crosses later resurfaced in commemorative celebrations.

More often than not, local commemoration was manifested in mundane, rather than monumental, deeds and expressions. Souvenirs from the period served as aides-mémoire through which 1798 was remembered in numerous households. In the outskirts of Ballina it was recalled how locals greeted the French soldiers marching to the town: ‘And the children pulled at the shiny buttons in the sogers’ coats and began crying to get them. The sogers with their bayonets cut off the buttons and gave them to the children. And the buttons were kept in some of the houses.’ There is testimony that French tunic buttons were later given as heirlooms to relatives who emigrated to America so that they could take with them a memento that recalled their native heritage.

These examples are a select sample of the copious traditions by which the French invasion and local rebellion were remembered. Altogether, this particular case is but one of countless episodes that were tenaciously recalled in folk history.

Facing the challenge

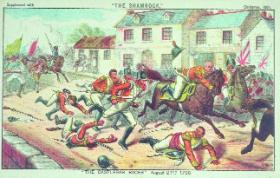

‘The Castlebar Races’ by John D. Reigh. (Shamrock, Christmas 1887)

How can historians come to terms with the multifarious ways in which history was remembered and commemorated on a ground level? On the face of it, such vernacular historical engagements can complement existing historiography. Narratives garnered from folklore could conceivably be appended to existing reconstructions of the past in order to showcase the ‘voices of the people’. However, such crude incorporation would not satisfactorily address the radical challenge posed by ‘folk memory’, which offers alternative ways to represent the past. It diverges from conventional history not only in content but also in form.

As opposed to histories dominated by voices of individual academics (who, to echo the post-colonial critique of Edward Said, characteristically prefer to speak with authority for the ‘common’ people rather than listen to what they have to say), folklore is inherently polyphonic. Folk history is a ‘people’s history’ featuring multiple narratives that refer to numerous people and are told in different versions by various storytellers to assorted audiences. This kaleidoscopic complexity amounts to a democratic history that was by no means free of local prejudices and politics, though these did not necessarily correspond with prevalent suppositions about ‘traditional’ nationalist history. Seanchas (to use the Irish term for folk history), which was aptly described by James Hamilton Delargy of the Irish Folklore Commission as ‘orally preserved social-historical tradition’, appeared in a variety of genres, including stories, songs, ballads, poems and rhymes (that sprang from both Irish and English language traditions), proverbs and sayings, toasts, prophecies, place-names, and an array of commemorative ritual practices. The various resourceful and sophisticated modes through which history was habitually recounted deserve scholarly recognition.

Historical examination of folklore implies that definitions of centrality and peripherality, and perhaps even the tenets by which the study of Irish history has been conceptualised, could be rethought. After recounting the parable of the fabulous stained glass window made from the shards that had been thrown away by the master, Macaulay concluded: ‘It is so far superior to every other in the church that, according to tradition, the vanquished artist killed himself from mortification’. Rather than succumbing to smugness, one can only hope that professional practitioners of Irish historiography will rise to the challenge of regeneration and explore other ways of crafting the past with respect to indigenous traditions.

Guy Beiner lectures in history at Ben Gurion University, Israel, and is also the current NEH Keough Fellow at the University of Notre Dame.

Further reading:

G. Beiner, Remembering ‘The Year of the French’: Irish folk history and social memory (Madison, 2006).

H. Glassy, Passing the time in Ballemenone: culture and history of an Ulster community (Philadelphia, 1982).

J. Fentress and C. Wickham, Social memory (Oxford, 1992).

The author is grateful to the Head of the Department of Irish Folklore at University College Dublin for permission to consult and publish material drawn from the Irish Folklore Collections.