‘RAGS AND BOUGHS’—DAUGHTERS OF THE IRISH GREAT HUNGER IN AUSTRALIA

Published in Features, Issue 1 (January/February 2022), Volume 30By Anne Casey

On 16 December 1848, fifteen-year-old Catherine McNeill from Roscommon was one of 234 girls to board the Digby, the fifth ship of the Earl Grey scheme to ferry its live cargo of Irish orphan girls to Australia at the height of the Irish Great Hunger. Departing one of Ireland’s worst-hit counties—which would lose a third of its people during the five-year national disaster—that journey would condemn at least three generations of Catherine’s family to destitution and cyclical incarceration in their new country.

HOSTILE CONDITIONS FOR THE IRISH ORPHAN IMMIGRANTS

Throughout the 1830s and 1840s, the British colonial authorities had been making concerted efforts to address the enormous gender imbalance in Australia, principally through assisted emigration schemes. There was a one in five chance, however, that an emigrant would not survive the gruelling voyage of more than three months on overcrowded, disease-ridden ships to reach the new colony, and there were additional challenges for women, particularly if unaccompanied, as many sustained sexual assaults on board. On top of the difficult journey, harsh conditions in the colony and its largely penal profile had proved attractive only to the most desperate of women.

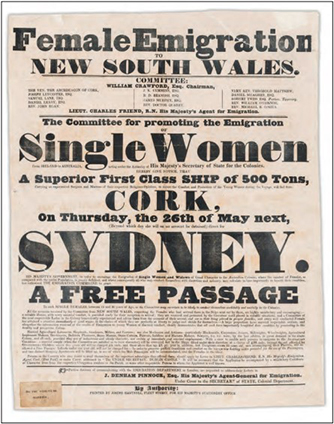

Above: Poster advertising assisted female emigration to New South Wales, c. 1835. Throughout the 1830s and 1840s the British colonial authorities had been making concerted efforts to address the enormous gender imbalance in Australia, principally through assisted emigration schemes. (State Library of New South Wales)

The Irish famine presented the British government with a unique opportunity to simultaneously advance two political objectives—to dispose of a proportion of the 55,000 children imposing on the public exchequer in Irish workhouses and put them to ‘good use’ in the colony as domestic servants, and to aid rapid population growth. Between 1848 and 1850, under the ‘Earl Grey scheme’ (named after the secretary of state for the colonies), 4,175 Irish orphan girls aged between fourteen and nineteen were drafted from workhouses throughout Ireland and shipped to Australia.

Travelling alone—having lost her parents, Pat and Betty—Catherine McNeill was recorded on the Digby’s indent as an illiterate ‘housemaid’ in ‘good bodily health’ and of ‘good probable usefulness’. The mariner’s report showed that ‘typhous fever’ had swept through the ship, claiming the lives of sixteen-year-old C. Duggan and seventeen-year-old Mary Ferguson before it docked in Sydney on 4 April 1849. By the time Catherine landed in Australia, public sentiment—fuelled by inflammatory press coverage—had turned against the young female importees. Circumstances in Ireland having contributed to their lack of education and work skills, the orphan girls were found to be unsuitable for domestic service. One year later, The Argus newspaper reported:

‘… such degraded beings as the majority of the female orphans have been found … brings a melancholy increase to the vice and lewdness that is now to be seen rampant in every part of our town … we have received no good servants for the wealthier classes in the towns, no efficient farm servants for the rural population, no virtuous and industrious young women, fit wives for the labouring part of the community’.

Local hostility led to the scheme’s cancellation the same year.

Like other Irish immigrants, the famine orphan girls sought the comfort and support of connections from their home country. This resulted in their clustering in larger towns and cities, limiting their employment prospects. Domestic positions were poorly paid and opened these young women to both physical and sexual abuse by their employers. Many were eventually forced into petty crime and prostitution for survival, making them particularly susceptible to arrest and removal of their children to institutions—a fate that would befall Catherine McNeill and her daughters. The overrepresentation of Irish women in gaols at this time provides ample evidence of their difficulties.

NEW LINKS BETWEEN IRISH FAMINE IMMIGRANTS AND INTERNED DAUGHTERS

Research into the Newcastle Industrial School and Reformatory for Girls in New South Wales, where 193 girls aged between four and sixteen years were interned from 1867 to 1871, has revealed a striking prevalence of Irish girls in the institution. It shows a substantial cohort of girls at Newcastle linked to Irish famine immigration, and a significant cluster who were daughters of the Earl Grey Irish famine orphans sent to Australia.

More than half of the Newcastle inmates either were Irish-born themselves or had one or both parents born in Ireland. Well over a quarter of the inmates were from Irish families who had arrived in Australia during famine-affected years. Perhaps the most compelling finding is that almost one in ten of all inmates—and eight out of ten inmates from families that arrived in the famine years—were daughters of Earl Grey famine orphans.

Most of the Newcastle inmates were sent there under a court order, having been arrested for vagrancy, prostitution and/or petty crime. The girls were sentenced to a minimum of twelve months in the institution, many experiencing repeated incarcerations in other facilities, and many ensnared in involuntary apprenticeships as domestic help for lengthy periods afterwards.

Original copies of letters between the school authorities and the colonial secretary document brutalities suffered by the inmates at the school, including being dragged by the hair, locked in solitary confinement on restricted bread and water rations (‘low diet’), being verbally abused and humiliated, and being subjected to a ‘virgin’ test (a physical examination by a male doctor performed on girls as young as six years old—a practice which later came under scrutiny). Children as young as ten years old were placed in solitary confinement for up to two weeks at a time. Not surprisingly, the more spirited girls rebelled, reports of their ‘scandalous’ escape attempts and disturbances making the national headlines. An official investigation led to the abrupt closure of the school in 1871 and the inmates’ transfer to Bileola Industrial School for Girls on Cockatoo Island in Sydney Harbour.

Above: Women and a girl in front of a bark hut in Lucknow, New South Wales, 1870–5—not unlike the ‘miserably constructed shelter composed of rags and boughs’ in Cooma, further south in the New South Wales outback, where Catherine Rudd was arrested in August 1868. (State Library of New South Wales)

‘A DEPLORABLE PICTURE OF A FAMILY IN THE BUSH’

The story of Catherine McNeill and her family encompasses many of the factors that had sabotaged the successful transplantation of Irish famine-affected women to Australia. Within months of her arrival in Australia, fifteen-year-old Catherine had married James Rudd—a man 30 years her senior—in Berrima, 131km south-west of Sydney. She and her husband registered the births of six children before James died in 1867.

On 1 September 1868, the Sydney Morning Herald reported Catherine’s arrest in Cooma market square with her daughter (also named Catherine). Police attending the campsite where the family was living found ‘a miserably constructed shelter composed of rags and boughs’. They arrested Eliza (14), Catherine (12) and James (10). The children were charged with ‘living and wandering about in company with their mother, Catherine Rudd, a vagrant and reputed prostitute’. Eliza and Catherine junior were sent to Newcastle Industrial School for Girls and James to an industrial school for boys aboard the Vernon, anchored in Sydney Harbour.

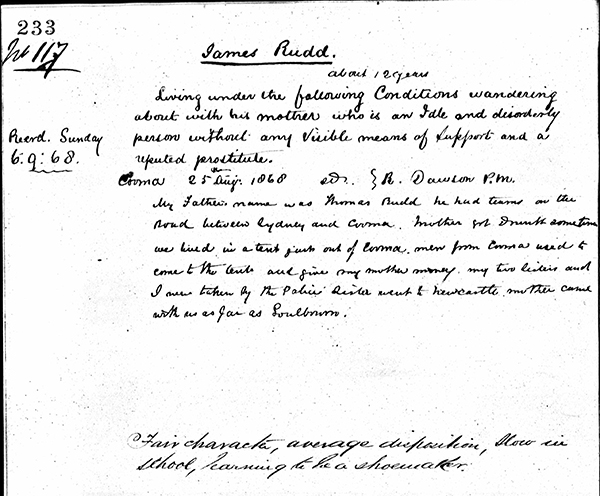

Above: ‘Living under following Conditions wandering about with his mother who is an Idle and disorderly person without any visible means of support and a reputed prostitute’—the admission record of James Rudd (‘about 12 years’) to the boys’ industrial school on board the Vernon in Sydney Harbour, 6 September 1868. (Ancestry.com)

In his admission record dated 6 September 1868, Catherine’s son, James, revealed the family’s tragic change of circumstances. According to James, their father had been running teams of cattle up and down to Sydney prior to his death:

‘My Father’s name was Thomas Rudd—he had teams on the road between Sydney and Cooma … We lived in a tent just out of Cooma. Men from Cooma used to come to the tent and give my mother money. My two sisters and I were taken by the police.’

Given the family’s dire circumstances, it is beyond doubt that, like so many of her compatriots, Catherine had made the pragmatic decision to sell her body in order to feed her children.

Catherine was remitted to Goulburn Gaol for three months. It is unlikely that she was ever reunited with her children, as she died in 1874, aged 41. Her unfortunate legacy would further subjugate her daughters, carrying forward into the next generation. When Catherine died, her daughter Eliza—who had been apprenticed from the Newcastle school and absconded—had been recaptured and once more detained.

Catherine junior made the headlines again when—eighteen months after her apprenticeship from the Newcastle school to a remote cattle station 485km north-west of Sydney—the Armidale Express reported that she had been charged with concealing the birth of her illegitimate daughter in her servant’s quarters. The Sydney Morning Herald detailed that:

‘… a newly born infant was found in a box at the residence of a Mr Rodgers … There were no marks of violence found on the body, consequently it was buried by the police. The mother of the infant, whose name is Kate Rudd, is one of the Bileola girls, and was well recommended. Everyone in the house was very kind to her, and tried to encourage the unfortunate to do right … The cause of the girl’s trouble is far away from here. He is a person with whom she was acquainted in Sydney.’

Catherine’s circumstances, her distance from Sydney and her time served in the apprenticeship tend to controvert the reported paternity story, opening the possibility of abuse by her employer. She was remanded for trial and was eventually acquitted. She went on to marry several times and gave birth to two boys and five girls, few surviving their first year. Her baby daughter, Charlotte, was admitted with Catherine junior to Armidale Gaol in 1884, when she was recorded as ‘a 27-year-old Catholic laundress’ following her arraignment on a ‘drunk and disorderly’ charge.

CONCLUSION

The Irish famine orphan immigrants to Australia endured severe discrimination owing to their poor, Irish and Catholic origins, resulting in destitution and repeated imprisonment with repercussions that affected later generations. Their tragic legacy extended to their daughters, who were also extremely vulnerable to repeated arrests and incarcerations—their removal from their families effected by legislation driven by colonial policy. The story of Catherine Rudd (née O’Neill) and her family is one small chapter in a greater, largely untold, history of hardships endured by Irish female famine immigrants and their daughters in Australia.

Anne Casey is an Irish poet and writer, currently researching the intergenerational legacy of the Irish Great Hunger in Australia, funded by an Australian government research scholarship.

Further reading

D. Fitzpatrick, ‘Irish immigration to Australia 1840–1914’, Bulletin of the Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies 2 (3) (1989).

J. Ison, The Newcastle Industrial School for Girls: their infamy is lost to history (Newcastle, NSW, 2012).

D. Kerr, The Catholic Church and the Famine (Dublin, 1996).

V. Molinari, ‘The emigration of Irish famine orphan girls to Australia: the Earl Grey scheme’, in M. Ruiz (ed.), International migrations in the Victorian era (Leiden, 2018).