Quakers & the Famine

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Features, Issue 1 (Spring 1998), The Famine, Volume 6

A soup kitchen run by the Society of Friends in Cork, 1846-47

When the potato crop failed due to blight in 1846 it was obvious, in Ireland at any rate, that a major catastrophe was about to occur. The first failure in 1845 had been partial but it left the country debilitated with reserves run down, while individuals had few possessions left to sell or pawn.

Few Quakers in worst affected areas

Members of the Society of Friends (Quakers) were amongst those who understood the seriousness of the situation and many of them reacted by setting up relief operations in their own areas. In the autumn of 1846 soup kitchens were set up by Quakers in towns such as Waterford, Enniscorthy, Limerick, Clonmel and Youghal. Any thought of setting up a more comprehensive relief programme was hampered by two drawbacks. First, the number of Quakers in Ireland was small—a mere 3,000 or so out of a population that exceeded eight million. Second, the Quaker population was concentrated in certain areas and was almost entirely absent from the west, including Donegal, Kerry, Clare, west Cork and the whole of Connaught. Quaker relief, therefore, could not be offered directly in the areas which would suffer most.

The Society of Friends had certain advantages, though, if the right method of providing relief could be found. Quakers had a well-developed network of committees which operated on a nation-wide basis to organise their own society. Through these committees and through family ties Quakers throughout Ireland were in close contact with each other and with those in Britain. Many Irish Quakers were merchants and would have had the organisational capacity to purchase goods and move them efficiently to other parts of the country. Above all, Quakers believed that God was present in everyone and this gave an understanding that the individual in distress should be helped if at all possible.

Relief committees established

It was with this in mind that a number of Quakers, led by Joseph Bewley, organised a meeting in November 1846. The outcome was the establishment of a twenty-one member ‘central relief committee’. To facilitate frequent meetings membership was confined to the Dublin area, while a further group of twenty-one would be nominated as ‘corresponding members’ and from the Quaker community outside Dublin. Following discussions with their Irish counterparts Quakers in London also established a relief committee.

Throughout the Famine these two committees worked closely together, with the Dublin committee looking after grants of food and clothing while the London committee raised funds. The division of labour was not strict, however, and many English Quakers came to Ireland to see for themselves just how bad the situation was and to become involved directly with the giving of relief. As the work of these committees progressed they set up various subcommittees to handle specific tasks and amongst these were local committees in Waterford, Cork, Limerick and Clonmel which looked after relief operations in the south and south-west.

57 South William Street, Dublin-headquarters of the Central Relief Committee in its early months.

Food and clothing

The first and most obvious means of assisting the hungry was through direct grants of food or the money with which food could be purchased. Some of this went to Quaker relief workers in the field but the scope for this kind of aid was limited by the size and distribution of the Quaker community. A great deal more was done through assistance to non-Quakers who were running local relief efforts and through Quaker workers identifying local people who were capable of operating soup kitchens and encouraging them to become involved. In essence, the relief committees of the Society of Friends acted as intermediaries who encouraged those who had something to offer to donate it and then made these donations available to local activists. In their own words the Quaker workers provided a ‘suitable channel’ through which aid was brought from the donors to the recipients.

Before long the committees became involved in the distribution of clothing. In the winter of 1846/47 a large proportion of the clothing donations came from English committees, mostly consisting of women. Some clothes were made by the donors and others came from factories as a result of pressure from the women’s committees. A warehouse was taken in Dublin to receive donations and sort them into bundles for passing on to the destitute. In the following winter American donations were predominant and this was mostly in the form of fabrics so that employment could be generated in making clothing.

In the summer of 1847 there was a major change of direction in the type of relief offered by the Quaker committees. The emphasis on grants of food and clothing was greatly reduced in favour of longer term means of assistance. There were many reasons for this. First, there was a change in the type of relief offered by the government: soup kitchens were established by the poor law unions to feed the destitute without admitting them to the poor house. The Quakers recognised that there was going to be a hiatus following the closure of the public works schemes and before the poor law unions could set up the soup kitchens. They ensured that their own relief efforts were kept going to bridge that gap as far as they could manage but once the government soup kitchens were established they saw no point in duplicating them.

Second, the Quaker relief committees were suffering from both donor fatigue and physical fatigue. In essence, their operations had been established to meet the shortages expected in 1846/47 and many of the donors had given all that they could afford. The resources of the relief committees had been carefully managed over the year but there was a comparatively small amount left by the summer of 1847. With the co-operation of the government a survey was carried out among the officials who ran the poor law unions which showed that the magnitude of the destitution was so great that the resources of the Quaker committees could not even scratch the surface. Their original assertion was that ‘if there be one thousand of our fellow-men who would perish if nothing be done, our rescue of one hundred from destruction is surely not the less a duty and a privilege, because there are another nine hundred whom we cannot save’. In theory this maxim should remain valid if the proportion was one hundred out of hundreds of thousands, but in practice the resources available might not have saved anyone at all given the scale of the destitution.

Instead, it was felt that meagre resources should be kept only for those who were not eligible for government assistance and for longer term projects. Members of the Society of Friends had always felt that the only way to make a lasting contribution to help solve the problem was by means other than short-term distribution of food. The first moves towards this type of aid came in the early days of the Quaker involvement when cash donations were given to people in Galway and Mayo who had set up local employment schemes, mainly involved with weaving and other textile production. As time went on, however, a greater variety of projects were undertaken or supported.

Fisheries

In a famine it is a natural reaction to seek alternative ways of producing food and Quaker workers sought to do this through assistance to fisheries. In the early stages of the relief efforts Quaker travellers in Galway discovered that the fishermen of the Claddagh had pawned their nets and other equipment during the previous year and were destitute. Through cash loans the tackle was redeemed and the fishing community became self-sufficient again. Similar aid was given to fishermen in such centres as Kingstown, Arklow and Ballycotton and for a small initial input poverty-stricken communities were given back the means of supporting themselves. In the main the loans were repaid within a short time and the funds became available again for other purposes.

Not content with helping existing fishing communities the Quaker committees became involved in projects to foster new fisheries. For a variety of reasons these were not successful—distance from markets and the lack of bait due to the destruction of shellfish beds by the starving population. Fishery projects at Achill and Ballinakill Bay, near Clifden, did not last long. Another, at Belmullet, kept going for two years from the end of 1847 and some fifteen fishing boats and ten curraghs were fitted out. Ultimately this project failed through bad management by the proprietor. A fourth project was undertaken at Castletownbere in west Cork from the autumn of 1847, lasting for nearly five years and employing fifty-four men and boys. Eventually this, too, failed through bad management.

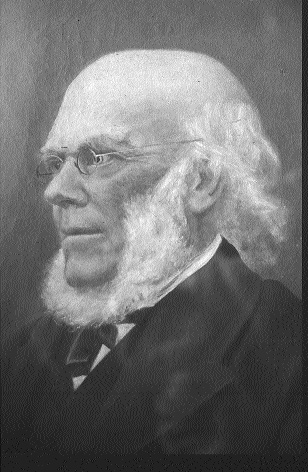

Richard D. Webb, who toured Mayo and Galway in May 1847 for the Central Relief Committee. (Friends Historical Library)

Probably the most worthwhile fishery project was that which was established at Ring through the initiative of the local Church of Ireland vicar and which was given financial support by the Quaker relief committee based in Waterford. This provided work and food for a number of families and for a time a fish-curing plant was operated here with Quaker funding.

Seed distribution

In the spring of 1847 an English Quaker, William Bennett, arrived in Ireland with the intention of touring the worst-hit areas. He believed that as the potato had proved to be an unreliable source of food there was a need to encourage a greater diversity of crops. To this end he and his son acquired seed from W. Drummond and Sons in Dawson Street. His main choice was turnip seed together with carrots and mangelwurzel and later he included cabbage, parsnip and flax.

William Bennett distributed most of his seed in Mayo and Donegal and while he was there he also made cash grants to local craft industries that had been set up to provide employment. After six weeks he returned to England where he published a book entitled Six Weeks in Ireland and this was influential in encouraging the flow of donations.

Some of the local Quaker committees became involved in the distribution of seed but the central committee in Dublin was hesitant, believing that any crops grown would be distrained by the landlords in lieu of rent owed. However, in May 1847, Sir Randolph Routh, the government’s Commissary-General, gave some eighteen tons of seed to the committee for distribution. The task of organising distribution was given to William Todhunter, who managed to do so by means of the postal system together with free carriage donated by a coach company and a steampacket company. Some 40,000 smallholders received grants of seed and it is estimated that 9,600 acres of crops were sown.

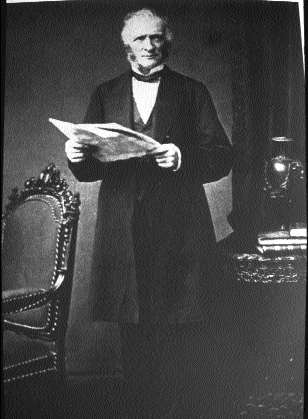

Jonathan Pim, one of the secretaries of the central relief committee. (Friends Historical Library)

Following the success of this operation the Quaker central relief committee repeated the exercise in the spring of 1848, laying out an initial sum of £5,000 to purchase and distribute almost sixty tons of seed. It is estimated that 32,000 acres of crops were grown as a result and that about 150,000 people would have been supplied with food as a result.

Agricultural improvement

The next logical step after the distribution of seed was to become directly involved in agriculture. Members of the Society of Friends who were involved in the relief operations could see that the government relief works did nothing to improve the long term prospects of the country as they were mostly concentrated on non-productive tasks. In 1848 the idea of undertaking agricultural reclamation works was put forward as a more useful operation.

The initiative came from a group of landowners on the borders of Mayo and Sligo, near Ballina, who approached the central relief committee in the spring of 1848 with an offer of the free use of land for a season. The offer was taken up, some 550 Irish acres, equivalent to about 360 hectares, were selected for the scheme and more than a thousand people were taken on to prepare the land for crops using spade labour. The workers were paid by the task, but unlike the government works of the previous season, the rates of pay were higher than normal to allow for the lower productivity to be expected from people debilitated by the effects of famine and disease. The cost of this project was about £300 in a normal week but reached £500 a week from time to time. Part of the cost was laid out in the purchase of fertiliser and care was taken to use only imported fertiliser to avoid distorting the local market and pricing it out of the reach of other farmers.

A variety of crops was sown and again the turnip formed a large part of the operation, while for obvious reasons no potatoes were sown. In order to bring some diversity of employment a certain quantity of flax was also introduced. However, when the harvest came this spade-cultivation experiment proved very disappointing in its yield. Various reasons were advanced for this, including the previous condition of the land, a factor which seemed to be borne out when the landowners managed a far better yield in the following season. In all, however, the project was a success in its main two aims to provide employment and to teach small-holders how to manage alternative varieties of crops.

The central relief committee was also involved in a number of similar projects on smaller scales through the giving of loans for spade cultivation to local landowners. The success of these was often better than that of the Ballina project and in general the loans were repaid.

A further benefit of the various agricultural schemes was the effect on the local economies. Some of the landowners involved in these projects commented that the numbers of people dependant on the local poor law unions had greatly decreased with a consequent reduction in the rates. One commentator in Fermanagh estimated that the poor law rate in the district where his spade cultivation scheme had operated was as little as 12 per cent of the local average.

Following the experience in Ballina a proposal was put forward to the central relief committee that it should establish a model farm for the more effective teaching of methods of growing crops and to act as an example of how a well-run farm should operate. A suitable property was found at Colmanstown in east Galway in the spring of 1849 and an extensive range of farm buildings was constructed. Before the farm could become fully operational a considerable amount of land reclamation was required and this involved the removal of ditches to create larger fields and the laying of land drains. A stream was diverted to supply water to a mill which would carry out the threshing and milling of the grain crops.

Some 228 people were employed on the Colmanstown model farm and a variety of crops was grown including grain and green crops, while there was also a wide range of farm animals such as cattle, sheep and pigs. This project was continued long after the end of the famine, only coming to an end in the early 1860’s when the property was sold.

Industry

In line with the belief that longer-term changes were needed the Quaker relief operation sought to encourage the diversification of the economy and this included various industrial projects. An attempt was made in 1848 to become directly involved through the establishment of a flannel manufacturing operation in Connaught. While the project was considered to be worthwhile and machinery was found for the task, at a late stage the committee shied away from direct involvement, deciding instead to offer financial backing to any suitable person who wished to take on the enterprise. Unfortunately, no one came forward.

A number of loans and grants were given to others who were providing industrial employment, ranging from small scale cottage industries to factory or mill-based enterprises. Amongst the latter were flax mills set up in the Ballina area as a direct result of the Quaker spade-cultivation exercise in 1848.

Campaigns

The Society of Friends was in frequent contact with the government and in a number of ways these contacts were useful and successful. In the early stages the London committee persuaded the government to make available two steamships to bring supplies collected in Britain over to the west coast of Ireland. A little later the government was prevailed upon to pay the considerable cost of transporting American food across the Atlantic. A major operational cost within Ireland could have been the transport and storage of food but an agreement with the government commissariat removed the cost and responsibility entirely. Under this arrangement all food landed in Ireland for the Quaker relief operations would be handed over directly to the commissariat in exchange for a credit note. This note could be used at any commissariat depot throughout Ireland to draw down supplies of food for distribution locally.

The London relief committee succeeded in persuading the Admiralty to update the charts of the west coast of Ireland as the existing charts had proved to be extremely inaccurate and useless for fisheries. Other campaigns undertaken included putting on pressure to have certain controls on fishing relaxed to improve the amount of food available.

The greatest of these campaigns was the attempt to persuade the government to make fundamental changes in the system of land tenure. Much of this work was carried out by Jonathan Pim, one of the secretaries of the Dublin committee. He published a book on the subject in 1848 and he had a part in the final drafting of the Encumbered Estates Act of 1849. Long after the famine was over Jonathan Pim continued his campaign for land reform and in 1865 he entered parliament as a member for Dublin.

Model Farm at Colmanstown, Co. Galway was built by the Cental relief Committee in 1849

It is likely that he was heavily involved in the drafting of later land acts, even after he had left parliament.

Assessment

When the central relief committee published its report in 1852 it concluded that its famine operations had not been a success. In the context of the time this was the only possible conclusion as no organisation could celebrate the success of a relief operation in the light of the massive toll of death and emigration.

Looked at another way, however, this cannot be deemed a failure. The extent and variety of the Friends’ relief operations were out of proportion to the mere 3,000 members of the Society in Ireland. The total of £200,000 that was handled by the Quaker relief bodies was a small part of the total from all sources but it nevertheless represents about £11 million at today’s prices. Nearly 8,000 tons of food were distributed along with almost 300 soup boilers and nearly 80 tons of seed. Countless numbers of people were given employment in agriculture, fisheries and industry and many more were taught how to grow crops which had previously been unfamiliar to them. While the relief was organised by a religious body there was a strict rule that there were to be no religious strings attached.

The exercise was not without its toll among the Quaker relief workers. The strain of intense involvement over a protracted period affected the health of many workers and some died. Others contracted famine diseases in the course of their relief works. It is not known how many died either directly or indirectly as a result of their involvement but the few who are known include Joseph Bewley, the leading light in the Dublin operations, who died of a heart attack at the age of fifty-six through over-work. Jacob Harvey, who was central to the operations in New York, also died through over-exertion as did William Todhunter, who was aged forty-six. Abraham Beale of the Cork committee contracted typhus and died.

The selfless way in which these Quakers gave of their time, energies and even their health made its impact on the Irish psyche and to this day the famine relief efforts of the Society of Friends have not been forgotten in folk memory.

Rob Goodbody is a member of the Historical Committee of the Religious Society of Friends in Ireland.

Further reading:

R. Goodbody, A Suitable Channel: Quaker Relief in the Great Famine (Dublin 1995).

M.J. Wigham, The Irish Quakers: A Short History of the Society of Friends in Ireland (Dublin 1992).

Reproduction of Mantania’s painting-Fr Gleeson gives absolution to the 2nd battalion before the battle at Rue du Bois, 9 May 1915. (Kevin Myers)