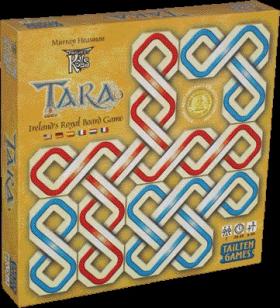

Project Kells—Tara: Ireland’s royal board game

Published in Issue 1 (Jan/Feb 2007), Pre-history / Archaeology, Reviews, Volume 15

‘The box’s graphics and layout are well designed.’

Project Kells—Tara: Ireland’s royal board game

Tailten Games E30

murray@tailtengames.com

by David Anderson

The initial impression given by this game is very good. The box’s graphics and layout are well designed. There is no doubt as to what kind of game it is, i.e. a historical-type as opposed to a fantasy board game.

Once opened, the box is seen to be jammed full of pieces along with instructions. The playing pieces consist of ringforts and kings. These look good, are well manufactured and robust—even the fragile-looking king pieces. Factions are clearly differentiated by colour, so there can be no claims of ‘I moved yours by mistake’. Apart from the pieces and instructions, there are ‘variant’ cards that you place beside the game board to indicate which variant of the game you are playing, of which more later. The thin instruction booklet is colourful, concise and informative. A lot of thought has gone into its design.

One of the game’s big attractions is the illustrated rules sheet. This demonstrates every aspect of game play, from the most basic moves—like how your pieces move or how you interlink them—to every rule and move allowed. The sheet conveys a huge amount of information that otherwise would have to be spelled out in the rulebook. Examples are clearly illustrated, which saves one from ploughing through a lot of wordy explanations.

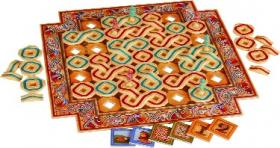

As each player joins his/her ringforts to create his or her own kingdoms or knots, with the red or blue pieces, a 3-D visual treat emerges. In this respect this game is head and shoulders above other games of its type. The playing board itself is another design success, not only because of its colourful ‘Book of Kells’ border but also because the basic playing pieces actually fit into the game board rather than just sitting on it. The player can add the link pieces between the ringforts or move kings about the board without fear of one accidental slip knocking all the pieces to the four winds and thus prematurely ending the game.

The playing pieces themselves come in three different types. The first is the basic playing piece, the ringfort. This is used to capture vacant hilltops, represented by the

The playing pieces ‘are well manufactured and robust’.

squares cut into the playing board into which ringforts fit. The ringforts have a coloured border, representing a faction, and a track around their outer edge into which a bridge piece easily fits. The next type is the bridge that is used to link various adjacent ringforts. The manner of linking ringforts creates the shape and number of knots and kingdoms. A group of connected ringforts is a kingdom, and this may consist of one large knot of ringforts or several different interconnected knots. The last type of playing piece is the king (three per side), which is shaped like a bearded Celtic king. These pieces have a square base that fits easily into the square holes in the ringforts.

The game itself is very easy to learn, thanks to the clear and concise rulebook and the illustrated sheet. An absolute novice to board gaming could be proficient and competitive within a very short time. It’s best to start with the basic variant of the game, ‘Sacred Hill’. This seems a simple game but can develop into a very tactical struggle. My first game took 10 minutes, but as we played my opponent and I learned various tactics and ruses so that by the third game play time was up to over 15 minutes. The goal of the initial game is to create the least number of kingdoms (generally speaking, the less you have, the larger they are) or knots. In the beginning, trying to create just one knot per kingdom is challenging, but with practice this gets easier. In the case of a tie in numbers of kingdoms or knots, you count the number of squares you control to decide who wins. So, although basically simple, it can quickly develop into a real battle of wits as different tactics are employed.

A second variant, ‘High Kings of Tara’, brings in the kings. There are certain things that they can and cannot do to influence the outcome of the game. The rules governing

The game’s creator, Murray Heasman, ponders his next move.

kings are superbly explained and demonstrated on the illustrated sheet, used in conjunction with the rulebook. While extra pieces and rules add a new dimension to the game, it does not become too complex. This level produces more complicated and challenging scenarios that really stretch the player and add to the enjoyment. The pieces move in the same way as a knight in chess, and the illustrated sheet demonstrates just how this works. There are no dice involved but players take turns to move. In phase one of either variant, a player picks a point from which to start. He places his initial ringfort on this spot and works out from there where to place further forts to build up a knot and so on. Ringforts must keep a certain distance from each other, as explained in the rules. Once the game develops to the point where a ringfort cannot be placed a knight’s move away from any other ringfort, the battle phase commences. Again the mechanics of the battle are all illustrated on the rules sheet. A third variant of the game, ‘Poisoned Chalice’, is equally well explained.

From a historical perspective, the game certainly has a very Celtic feel. The manufacturers have kept the whole Celtic look in all its aspects. Historically, the notion that you establish ringforts on hilltops in order to create kingdoms and eventually become High King of Tara is basically what ancient Irish warfare was about. Whether the moves in the game actually reflect the complexities of the power struggle in Ireland is another question, however. It might be more accurate to say that it relies on its name to convey the idea of Irish history, and that if one took away the name ‘High Kings of Tara’ it could simply be called ‘Celtic Kings’ and be applicable to any Celtic country. But this is not a major criticism and does not detract from its being a historical war game.

This is an entertaining game that is easy to learn and will appeal to novice and experienced player alike as no two games will play out the same way. It does give a feel for history and will surely encourage anyone who does not know about the High Kings of Tara to find out about them.

David Anderson is a war gamer of many years’ standing and a member of a medieval re-enactment society.