Prison Reform in Ireland in the Age of Enlightenment

Published in 18th–19th - Century History, Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Issue 2 (Summer 1995), Volume 3

Scaffold on the roof of Hosemonger Lane Gaol, London

Of the challenges they faced they found prison reform to be among the greatest. There was the popular view that people in jail were there because they were wicked and, therefore, deserved the punishment they received. To argue that no prisoner deserved that much punishment was an argument that too often fell flat in the public mind. This was (and still is) the commonly-held point of view. Take for example the complaint of the eighteenth-century British philanthropist, John Howard, who when he pleaded for compassion for prisoners found his listeners responding unsympathetically: ‘Let them take care to keep out’. The task of reform in such circumstances was never going to be easy.

The county jail

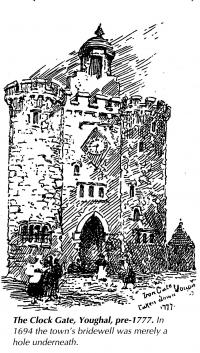

According to law each county in eighteenth-century Ireland had its own prison located in the chief town. In addition some large towns had their own jails although at times (to save on expenses) these were used jointly by both town and county. The law also required that every county have a house of correction (usually called a bridewell) where drunkards, petty thieves, rioters and vagrants were held for a few days before trial. Sometimes the few days stretched into years. Lunatics were also kept in bridewells. It appears that in practice this law was widely ignored. It is true that some towns had bridewells but they were very modest affairs such as that in Youghal which, in 1694, was merely a hole under one of the city gates. The temper of the times, however, permitted great laxity: thus a county jail, a city jail, and a house of correction were often combined in a single building where petty offenders (many of them children), persons awaiting trial, and convicted criminals awaiting execution or transportation, were crowded together in misery.

Debtors’ prisons

As well as jails for criminals and those accused of criminal acts, there were also jails for debtors, for anyone who could not pay his or her debts was liable for imprisonment. How many were confined for debt? The figures are inexact but we know that 705 (of whom forty-six were women) were imprisoned throughout Ireland in 1759. In 1796 there were 575. The number is high because people could be imprisoned for owing very small sums. A debtor’s prison was known as a marshalsea; the warden was called a marshal. Rarely did a town build a marshalsea, so it was usual to find that the marshal provided his own prison by renting a house for the purpose. Sometimes the town fathers secured a building for his use. In 1716, for example, the town of Cashel rented a building for £2 10s. per annum for its marshal. In 1717, Dublin city corporation actually built one and rented it to the marshal for £80 a year. It was, however, by no means unknown (again to save on expenses) that marshalseas and jails were located in the same building.

Overcrowding

A government report of 1796 lists fifty-one jails throughout the kingdom which would appear to be more than enough for a population of about five million. But actually, most of them were very small and remained so until a half-hearted prison-building programme began in the last quarter of the century. How small? In 1772, for example, the combined jail and bridewell of Cavan town was but a single room, eleven-and-half feet by six. The smallness of jails naturally led to serious overcrowding. In 1777, for instance, in the prison at Castlebar, forty-two prisoners were confined in one room twenty-one feet by seventeen. Another reason for overcrowding was the keeping of debtors in jails that were meant to house only criminals or those so accused. To add to the problem was the fact that it was not uncommon for the families and even servants of debtors to live with them. In 1787, for instance, it was disclosed that of the 227 people in the Dublin city marshalsea only 134 were prisoners; the remaining ninety-three consisted of thirty-six wives (or reputed wives), forty-eight children and nine servants. Added to the discomfort were the chickens, dogs and pigs families kept with them even though parliament (in 1763) had forbidden the keeping of cattle, fowl and swine in prisons under penalty of forty shillings per day per beast.

The Clock gate, Youghal, Pre-1777, In 1694 the town’s bridwell was merely a hole underneath.

Fees paid to jailors

Another reason for crowded jails and marshalseas grew out of the custom of paying fees to prison officials. No inmate was allowed to leave without paying fees to the local sheriff, warden or marshal and their assistants. This custom led to great hardships. An early eighteenth-century petition to the house of commons from 100 ‘superlatively wretched’ prisoners in Dublin city marshalsea describes how frequently people were arrested for as little as two shillings and then, having paid their debts, found that they could not leave the marshalsea until they paid the obligatory fees to the marshal and his staff.

Why fees? Jailers and marshals received very little in the way of salary. Parliament legislated on the subject for the first time in 1635 when it empowered justices of the peace to appoint the salary of the keeper of the local house of correction. As no sum was mentioned we can imagine that the lowest possible figure was the norm. In 1702, for instance, the town council of Waterford paid £2 per annum to the keeper of the house of correction but this included the duty of arresting vagabonds as well. He also earned sixpence extra every time he whipped a beggar.

Parliament said nothing more of jailers’ salaries until 1719 when it ordered county grand juries to raise £10 a year for jailers and £5 for the keeper of the house of correction. But by no means were they paid as much as the law allowed. Marshals, too, received salaries but they were modest. For example, in 1701, the marshal of Drogheda got £10 a year but out of that sum was obliged to pay £6 in rent for his marshalsea.

Marshals were expected to live chiefly from the fees and room rents they collected from debtors. But how much were the fees? Great latitude here led to scandals. In 1698, parliament, outraged at the huge fees levied on debtors in Dublin city, passed a bill regulating fees in the metropolis. Henceforward, every person committed to the municipal marshalsea was to pay the marshal 6s. 8d. and the same amount again on being discharged. Unfortunately, the new act referred only to Dublin and it was not until 1717 that parliament legislated for the whole of Ireland when it required all jailers to register their fees with a government office in Dublin and to post duplicate schedules in their prisons.

But what was the proper amount of fees? It was not until forty-six years later (in 1763) that parliament turned to that aspect of the problem when it enacted that jailers were to submit a table of fees to their grand juries. If approved by the grand jury, the schedule was to be posted in the jail and in the grand jury room. Nevertheless, one may well wonder how effectively such statutes operated when, in 1782, the keeper of Dublin’s New Prison (the country’s most important jail) declared that he had not hung up a schedule of fees ‘as he did not know it was so directed by any act’.

To remedy such deficiencies parliament again legislated for fees in 1784. The new act repealed that of 1763 and freed everyone held in prison solely for fees. All fees were abolished and in their place grand juries were allowed to raise whatever sums they thought proper to serve as recompense. Again, the statute was largely ignored.

Drinking

Another serious problem was drinking. Given the conditions of jails it was natural that many prisoners turned to alcohol which was inexpensive and easy to obtain. It was pointed out that

a noggin or gill of…whiskey, is sold in Dublin so cheap as one-and-a-half pence or two pence, and a half a pint for three pence or four pence. This makes it the common liquor of prisoners…who are often intoxicated by it almost to madness.

The quickest way to obtain the necessary money was extortion. In 1729 in one Dublin prison, it was said that

a practice prevails of taxing every prisoner that comes into the… prison…though it be but for a night, 2s. 2d….and if refused, the prisoner is abused, violently beaten and stripped. And it appears that convicted persons under the rule of transportation, are constantly admitted to be among the debtors, and to treat them with the utmost cruelty in levying this arbitrary imposition.

All attempts to stop the selling of liquor in prisons were for the most part frustrated by jailers, who usually kept a tap in the prison, thought it their right to do so, and obtained large sums by so doing. In 1783, the keeper of New Prison in Dublin (who earned on an average £400 a year from this trade) explained that it had been his constant practice to sell liquor which he considered a ‘legal perquisite’ necessary to supply ‘the deficiency of a salary which was otherwise insufficient for his support’.

The Tholsel, Carlingford, County Louth, c.1900- reputed to have once been the town jail.

Parliament bans drink

Parliament tried three times (1763, 1783, 1786) to make jails dry. For the most part, however, these acts remained inoperative. In 1788, in Dublin’s Newgate, ‘many instances’ were discovered ‘of persons dying by intoxication and fighting and that a puncheon of whiskey [about 80 gallons] had been drunk there in a week’. What kind of men served as jailers? The philanthropist, John Howard, described the perfect type:

A keeper should be firm and steady, yet mild, and he should visit every day the wards of his prison. Such a man will have more influence and authority than the violent passionate gaoler, who is profane and inhumane and often beating and kicking his prisoners.

However, beyond this and other similar pleas that only kind and competent men ought to be appointed little was said about this important question. No previous training was necessary. In 1751, a dancing master was appointed governor of Dublin city marshalsea. In 1796, the keeper of Nenagh bridewell was a shoemaker, the one at Roscommon a cabinet maker and pursued his trade in the jail, while at Sligo the jailer kept a public house opposite the prison.

Keeper Hawkins

Small salaries and the want of proper regulation led to serious complaints of corruption, cruelty and neglect being levelled against jailers and marshals throughout the eighteenth century. Many of these charges were by no means unfounded. In 1704, for example, a Dublin marshal was suspended from office because he had ‘greatly neglected’ his duties and, moreover, had become a prisoner himself. But the most infamous case was that of John Hawkins, governor of two Dublin prisons, Newgate and the sheriffs’ marshalsea. In 1729 the house of commons resolved that Hawkins was guilty of the ‘most notorious extortion, great corruption and other high crimes and misdemeanours’. It was disclosed that Hawkins (whose official salary as keeper of Newgate was £10 a year) had earned £1,163 annually from fees and perquisites besides that which he obtained from ‘infinite extortions’ and ‘premiums from stolen goods and other private perquisites peculiar to his employment, not to be computed or valued’. He had made it a practice to send thieves out of his prisons to bring back stolen goods and ‘the profits arising either from the sale or reward for finding them were equally divided among them’. Furthermore, when he hanged thieves he kept their stolen possessions all of which he asserted became his lawful property.

Although Hawkins was, assuredly, an outstanding specimen of a cruel and corrupt jailer there can be little doubt that the example he set did not want modest imitators. In 1784, for instance, the lord chancellor could complain of negligence in Newgate so ‘scandalous’ that ‘it was almost impossible to come into it without being robbed’. Moreover, he went on to declare that ‘a like mismanagement existed in all the gaols in the kingdom’.

Starving inmates

But of all the horrors prisoners in lreland faced, starvation was the worst. In 1665, parliament discovered that ‘great numbers’ of poor persons often starved to death in prison before their trials because they lacked money to buy food. As a remedy, parliament required every parish to levy a reasonable sum for the support of local prisoners. There is evidence that some good was done but it was haphazard. In 1729, for example, a committee of the house of commons investigating Newgate (Ireland’s largest prison) found a ‘multitude of wretched objects lying naked upon the ground perishing with cold and hunger’. The committee then discovered that several people had died of starvation and that there were many who sometimes for four days successively had not had any food at all. Why? The members of the committee were told that the custom of allowing bread had been ‘discontinued for some time past’.

The Enlightenment comes to Irish prisons

The attempts of parliament beginning in 1665 to reform Irish jails have been noted. There is no doubt that some good was accomplished but it was often too little or too late for some prisoners and nearly always quickly forgotten. Concerted reform can he said to have begun in 1764 with the publication of Cesare di Beccaria’s An Essay on Crimes and Punishments. Beccaria attacked the savage criminal proceedings and penalties of his day. He denounced the use of torture and secret trials. He criticised the death penalty and argued that not only was the certainty of punishment more effective than its severity but as well that prevention of crime was more important than punishment. The significance of Beccaria’s work was immediately recognised. Translated into twenty-two languages (it was published in Dublin in 1767), it stimulated a host of practical programmes of reform.

John Howard : Prison reformer.

John Howard

In 1773 (nine years after the publication of Beccaria‘s great work) John Howard, a man of wealth and influence became a sheriff of Bedfordshire in England. As part of his duties, Howard visited the jail at Bedford and was appalled at what he saw there. Like Irish jails, those of England and Scotland were miserable places overwhelmed by cruelty and extortion. Howard immediately dedicated himself to the cause of prison reform. In 1774 Howard persuaded the British parliament to pass two bills: the first discharged prisoners set at liberty in open court and the second abolished discharge fees. Howard had these acts printed at his own expense and sent to every jail in Britain. Years afterwards he complained that the acts had not been ‘strictly obeyed’.

In 1775, Howard made his first trip to Ireland. Over the next thirteen years he returned five times. In the years between, he gained a wide reputation visiting hospitals and jails all over the continent. John Wesley (the founder of Methodism), who met him in Dublin in 1787, thought of Howard as one of the greatest men in Europe. ‘Nothing’, Wesley said, ‘but the mighty power of God can enable him to go through his difficult and dangerous employments’. For Howard, Ireland was particularly formidable. Many areas of the country, he thought were ‘as savage as the inland parts of Russia’. As for government, every public institution in Ireland, Howard asserted, ‘is a private emolument. All are corrupt and totally inattentive’. And as for jails in particular, Howard declared that he never saw prisons or abuses worse than those in Ireland.

Parliament acts

Concerning the Irish parliament, he took a balanced view. ‘l have’, he said, ‘frequently referred to the Irish acts of parliament for the regulation of prisons, as containing many articles highly laudable and worthy of imitation. I am sorry, however, that it is necessary for me to say, that the police of this country in these matters is as defective in point of execution, as it is commendable in theory’. But, as a creature of the Enlightenment, Howard did not despair. His admonitions and those of Irish reformers together with the public annoyance that so little had been accomplished despite all the laws that had been enacted, led parliament at length in 1786 to pass the greatest prison reform bill of the eighteenth century.

The new act established a vast, and in some respects, an almost revolutionary code of prison regulations including a system of permanent inspectors chosen by the local grand jury. The inspectors were to visit their prisons at least once a week and to forward reports to the officer who was to be at the apex of the system, an inspector-general appointed by the viceroy. The inspector-general was required to visit every prison in the kingdom once every two years. Here at last was a powerful piece of legislation that would surely sweep aside the creaking, fumbling, halting mish-mash of statutes that had gone before.

In 1780, in Dublin’s Newgate many instances were discovered of persons dying by intoxication and fighting.

Improvement?

To some small degree it was true. Howard, who visited all the county jails during 1787-88 was pleased to discover that grand juries had spent money liberally to supply prisoners with ‘necessaries in sickness and health’. But abuses, though somewhat checked, had not vanished. He also found many prisons dirty and local inspectors negligent or dishonest. Prisoners were still being held for fees. Howard was not alone in his criticism. In 1787, one of the chief judges of Ireland described Dublin city marshalsea as ‘an hovel dreadful to imagination, a number of persons huddled together without even a little straw to lie on, surrounded by noisome stenches, and accessible only at the hazard of a person’s life—yet even this was nothing compared to the state of their bridewell’. Of the bridewell a member of parliament who visited it said ‘that no painting, nor any powers of words could convey an adequate idea of the place or the distresses of its inhabitants’.

Inaction

In answer to these criticisms parliament, in 1787, made a few minor revisions to the act of 1786 but thereafter nothing more was done. Two years later, in 1789, the French Revolution broke out and it, as well as the wars rising out of the ambitions of Napoleon, held the attention of governments everywhere leaving little time for problems of reform.

So the old laxity quickly returned. A good example was the report of the inspector-general, in 1796, in which he described what he had found at Kilkenny prison. The jail, he said, had no privy, pump, water, kitchen or common hall, the roof leaked and the felons had no fire, blankets, bread or light. Cavan jail, although built only ten years before, was already a ruin. The plans and materials of it were so bad and the work so dishonestly executed that to alter or repair it, the inspector-general thought, ‘would be a prodigal expenditure of the public money’. Moreover, the machinery for executing prisoners was ‘so very imperfect’ that a man hanged there ‘was so cruelly tortured that he remained for a long space in the agonies of death, till a pit was dug under his feet to end his torments’.

Conclusion

Why did reforms go awry? In part because dishonesty, incompetence, indifference and laziness were too strongly ingrained in the ruling class to be overcome simply by parliamentary statutes; and the tiny ruling class dominated everything. Remember how John Howard had complained that in Ireland every public institution was ‘corrupt and totally inattentive’? In part, as well, because Irish society, sunk in ignorance and rapidly growing poverty, was largely divorced from its governors by language and completely divorced by religious traditions. Little chance, therefore, for the ideas of the Enlightenment to take hold in such conditions. But at least this much can be said: prison reformers had laid, in law, a firm basis for eventual, real improvements.

Joseph Starr lectures in history at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh.

Further Reading:

C. Maxwell, Country and Town in Ireland under the Georges (Dundalk 1949).

R.B. McDowell, Irish Public Opinion, 1750-1800 (London 1944).

R.B. McDowell, The Irish administration, 1801-1914 (London 1964).

B. Henry, Dublin Hanged: crime, law enforcement and punishment in late eighteenth-century Dublin (Dublin 1994).