Pre- Norman Dublin: Capital oflrelandr by Se an Duffy

Published in

Features,

Issue 4 (Winter 1993),

Medieval History (pre-1500),

Pre-Norman History,

Volume 1

Wood Quay the heart of Pre-Norman Dublin.

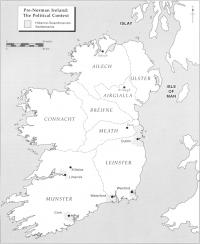

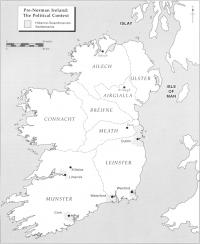

In the public imagination,the battle of Clontarf ranks as one of the great landmarks in Irish history. Traditionally, it has been seen as the contest in which Brian B6ruma died in the very act of bringing Viking power in Ireland to an end. Yet, for the Hiberno-Scandinavians who ruled Dublin – the Ostmen, as they called themselves – the events of 1014 may have been of less lasting consequence than a development which took place in the city nearly forty years later.

While it is true that Brian defeated the Ostmen on more than one occasion, he never managed (or never chose) to remove them outright from the rule of Dublin and assume its kingship for himself. This, however, is precisely what was to happen in 1052.

Diarmait mac Mail na mBo

In that year, the reigning king of Leinster, Diarmait mac Mail na mBo, marched his armies into the city’s rich hinterland – an area the Irish called Fine Gall (now Fingal in north County Dublin). He burned and harried his way as far as the dun or fortress at the city’s core, forced Echmarcach the Ostman king of Dublin to abandon the place and take to the seas, and then installed himself in what the annals call ‘the kingship of the foreigners’ (rfge Gal£). This was not just the assumption of a nominal title that meant little in practice. Until his death a full twenty years later, Diarmait mac Mail na mBo maintained a tight grip on Dublin. The highly rated Ostman army accompanied the men of Leinster on every military campaign they waged against their enemies; even more importantly, the fleet of warships that operated out of Dublin was at King Diarmait’s beck and call.The prestige and military advantage thereby gained was such that this man, who was the first of his dynasty for three centuries to attain even the kingship of Leinster, could with some justification claim to be king of Ireland, if only ‘with opposition’ (co fresabra). His principal rival was the king of Munster, Brian B6ruma’s son Donnchad, and most of Diarmait’s energies were given over to the contest for supremacy with him. But he needed a way of securing his hold on Dublin, and so, at some pOint soon after 1052, Diarmait mac Mail na mB6 installed his eldest or most favoured son, Murchad, as king of Dublin. This was a very important develop- ment, and Murchad has an important place in Irish history. The famous MacMurrough family are descended from him – Diarmait Mac Murchada, the man who instigated the English invasion of Ireland, was his grandson. Murchad was made king of Dublin partly, no doubt, because his father thought that the experience would be a good apprenticeship for his heir. But more than that was involved. Diarmait mac Mail na mB6 was a contender for the kingship of Ireland. Appointing his eldest son to Dublin helped to make that a reality, and in doing so he set a crucial precedent. As we shall see, it was a gesture repeated by each successful claimant to the kingship of Ireland over the next three-quarters of a century.

Bone trial-piece (late 10th-early 11th cent.) showing affinities with Manx and Anglo-Saxon art, discovered during recent excavations at Little Ship Street,

Dublin. (Courtesy of Linzi Simpson)

Dublin and the Isles

Other implications followed from Murchad’s rule over Dublin. From what we can tell, the ruling Ostman dynasty of Dublin had also exercised control over the Isle of Man and, to a lesser extent perhaps, the Western Isles of Scotland. This is a region which Irish sources call Inse Gall (‘the islands of the foreigners’), and it is where Echmarcach, Dublin’s exiled Ostman ruler, took refuge after his expulsion by the Leinstermen in 1052. Gaining control of Dublin, one of the most important trading centres in western Europe, meant an enormous increase in the power of King Diarmait and his son Murchad. But they were not content with it, and in 106 1 Murchad invaded the Isle of Man. He defeated Echmarcach in battle and the Manx paid him cain or tribute as a sign of his overlordship. From then until his ‘ death in 1070, Murchad reigned as both king of Dublin and of the Isle of Man. When his father was killed two years later, at the head of an army that included many hundreds of Ostman warriors, among the titles he was given by an annalist was ‘king of the Isles’ (ri Indsi Ga/O· It is worth pointing out that when Murchad died, he was formally interred in Dublin, and a poem which commemorates his death notes that ’empty is the dun without him’. These references suggest that this prince from south Leinster had made Dublin his home, and we can take it that in the two decades after 1052 the Leinstermen exercised a degree of control over Dublin and Fine Gall which no Irish ruler had ever previously exerted.

Toirrdelbach ua Briain

Toirrdelbach ua BriainThe deaths of Murchad and his father, therefore, left a void which anyone seeking to command authority in the region needed to fill. And thus, Leinster was immediately invaded by Brian B6ruma’s grandson, Toirrdelbach ua Briain of Munster, intent upon forcing the other province-kings to acknowledge his claim to the kingship of Ireland. This was not unusual, but Toirrdelbach’s next move was. He marched straight to Dublin and accepted the kingship of the city (rige Atha Cliath) from the Dubliners. The assertion of power over Dublin was becoming part and parcel of the race for the high-kingship. If nothing else, geography made the task of governing Dublin difficult for a Munster-based ruler like Toirrdelbach ua Briain, and for a short time he experimented with allowing local under-kings rule the city on his behalf. But in 1075 he opted for a change of policy, and followed the example set by Diarmait mac Mail na mBo by appointing his own eldest son as king of Dublin. This was the famous Muirchertach Mor Ua Briain who, increasingly over the

next forty years, came to dominate the Irish political scene. But Dublin was where ‘_ . ISLE!) OF MAN he served his apprenticeship and Dublin remained central to his strategic considerations throughout his career. During his father’s lifetime, Muirchertach used the forces of Dublin to invade the ailing province of Mide (Meath), and to overcome opposition to his father’s overlordship by Ua Ruairc of Breifne. Also, as early as 1073, within a year of Munster gaining control of Dublin,two members of the Ui Briain were killed in the Isle of Man. In gaining power in Dublin, they were keen to assert their dominance in the Irish Sea region as a whole, like the Leinstermen before them. That dominance may have receded temporarily following the death of Toirrdelbach ua Briain in 1086. A contest for the succession to Munster broke out between his sons and it was a number of years before Muirchertach M6r, having quelled his rivals’ dissidence, settled into the kingship and set about regaining mastery over the rest of the country. In the interval, a remarkable change had taken place in the government of Dublin. Just as the kings of Leinster and Munster had attempted, in seizing Dublin, to gain possession of its Irish Sea satellites, so the reverse now occured, and not for the last time: while Ua Briain’s back was turned, Dublin and Fine Gall were annexed by an ambitious warlord from the Isles.

Godred Crovan

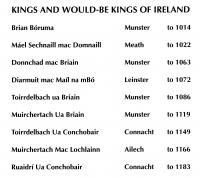

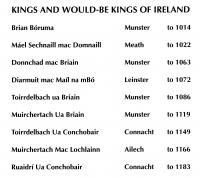

His name was Godred Crovan (known to the Irish as Gofraid Mer[mach) and he enjoys an important place in insular history because he founded a dynasty that ruled over Man and the Isles, in whole or in part, for the next two hundred years. Munster Meath Munster Leinster Munster Munster Connacht Ailech Connacht to 1014 to 1022 to 1063 to 1072 to 1086 to 1119 to 1149 to 1166 to 1183 seizure of Dublin from his base on the Isle of Man is further proof, if that were needed, that Dublin and Man were treated by contemporaries as a single political entity. The ruler of one was entitled to seek to add the other to his domain. lf we treat of the history of one without the other, we are missing a large part of the picture. In invading Dublin, Godred Crovan made an enemy of Muirchertach Ua Briain. What is more, he allied himself with Ua Briain’s leading rival for the highkingship, the northern king Domnall Mac Lochlainn of Ailech. The first major collision between Ua Briain and Mac Lochlainn was in 1094, and it is no accident that it took the form of an assault by the Munster army on Dublin: Dublin was what Muirchertach needed if his ambitions were to be realised. He banished Godred Crovan from the city and perhaps from Man also, because Godred died on the island of Islay in the following year. The Chronicle of the Kings of Man tells a remarkable story about what happened next. The chieftains of the Isles sent an embassy to Ua Briain, asking him to provide a regent to govern their kingdom until Godred Crovan’s young son came of age. Muirchertach willingly complied, appOinting his nephew, Domnall mac Taidc, to rule over them. However extraordinary it may seem that the king of Munster should have a role in providing Man and the Isles with a ruler, this story rings true, because the Irish annals report the death of Domnall’s brother Amlaib on the Isle of Man in 1096. It was a strange but revealing development. It shows just how rapidly Irish kings had begun to dominate the Irish Sea region once they laid hands on Dublin. And since the kingdom of the Isles was in some respects a no-man’s-land over which the leading powers in the region were prepared to come to blows, this new Irish hegemony was viewed by many with resentment and suspicion.

Magnus Barelegs

It was primarily to stop this develpment in its tracks that the famous Norse king Magnus Barelegs, the last great Viking warlord, led two naval expeditions to the West in 1098 and 1102. On the first of these, Magnus seized the Isles; on the second, he had his eye on Ireland itself, or so the Irish thought. Having based himself on the Isle of Man, Dublin was his next target, and there is evidence to suggest that he gained control of the city, like Godred Crovan a decade earlier. This development was unacceptable to Ua Briain, who decided to confront him at Dublin. However, a diplomatic compromise was reached. A marriage was agreed between Muirchertach’s infant daughter and Sigurd, the nine-year-old son of King Magnus. Magnus agreed to withdraw to Norway, leaving Sigurd behind as king of the Isles. The deal had much to offer Ua Briain. With Magnus out of the way, it was Muirchertach, and not his young son-in-law, who was likely to prove the real power in the region. As it turned out, though, he need not have worried. On his journey home in 1103 King Magnus landed on the coast of Ulster, where his raiding party was attacked, and he himself killed. He was buried in Downpatrick and was to be the last king of Norway to make a western expedition for over 150 years. At the news, his young son Sigurd cast aside his child-bride and returned to Norway. Domnall mac Taidc With the Norse intervention at an end, Dublin (and, presumably, Man) came back under Munster control. In 1105, when the country’s leading cleric, the head of the church of Armagh, sought to make peace between Ua Briain and Domnall Mac Lochlainn, it is significant that he did so at Dublin. Two years later, Muirchertach imprisoned his nephew, Domnall mac Taidc, in the city. This is the man who had been king of the Isles for a short period in the 1090s, and he was obviously now causing trouble for his uncle in the region. In fact, in 1111 Domnall invaded the Isles and forcibly seized the kingship against Muirchertach’s wishes. King Muirchertach came to Dublin, and spent a full three months from September to Christmas in the city, apparently trying to bring Domnall to heel. For the king of Munster to be able to leave his home province and spend a quarter of a year in residence in Dublin speaks volumes about the degree of control which the Munstermen had over the city, about the importance they attached to it as a satellite possession, and about the place of Dublin in the Irish polity – it was becoming, in effect, a home away from home for ambitious Irish dynasts. Not alone that, but it emerges before long that Muirchertach had continued the policy adopted by both his father and by Diarmait mac Mail na mB6: he had appointed his heir to rule Dublin. We only discover this when Muirchertach himself fell from power after being struck by severe illness in 1114. Thereupon, the Leinstermen, whom he and his father before him had excluded from the control of Dublin for forty years, decided to challenge for it again. They were led by Donnchad mac Murchada, father of the infamous Diarmait, They marched their army on Dublin but were defeated by the Munstermen and the Ostmen, led by Muirchertach M6r’s son Domnall Gerrlamhach, acting as their king. Donnchad mac Murchada was killed in the battle: according to Giraldus Cambrensis, the Ostmen showed their true contempt for the Leinstermen by burying him with a dog in their own assembly hall. Over half a century later, Diarmait Mac Murchada inflicted a bloody revenge on the Dubliners for this humiliating insult.

Toirrdelbach Ua Conchobair

The great tragedy for Muirchertach Ua Briain was that, although he and his father had built up a tremendous position of power in Ireland, the dominance of the Ui Briain withered away at Muirchertach’s demise because his sons were weaklings. Although Domnall Gerrlamhach defeated Leinster in the battle of Dublin in 1115, he was no match for the new rising star of the Irish political scene, Toirrdelbach Ua Conchobair of Connacht. In 1118, therefore, Ua Conchobair marched to Dublin, laid the city under siege, expelled Domnall from the kingship, and made himself king. The symbolism is allimportant. With Muirchertach Ua Briain out of the way, the kingship of Ireland was vacant, and Ua Conchobair was making his bid for it. He did so by marching his victorious armies on Dublin and accepting its kingship from the populace. But it was not a hollow gesture. When he brought a great fleet onto the Shannon in the following year, and sailed as far south as Killaloe, the leaders of the Dublin Ostmen – now his loyal vassals – were in the host. And when the bishop of Dublin died in 1121, and a dispute arose as to the succession, Toirrdelbach in his capacity as Rex Hiberniae sided with the ‘burgesses of Dublin’ (burgenses Dubliniae) in their episcopal choice. But Ua Conchobair faced a problem in that, being based in Connacht, Dublin was a little out of his reach and difficult for him to exert control over. Though the Munster kings suffered the same handicap, it was not to the same extent, probably because they already governed Limerick and Waterford, and Dublin was merely a glamorous addition to this network of maritime outposts. King Toirrdelbach accordingly acquiesced to some degree in the subordinate rule of Dublin by the Meic Murchada of Leinster. However, when Enna Mac Murchada died as king of Leinster and Dublin in 1126, Toirrdelbach responded dramatically by making what the annals call a ‘royal journey’ (righthe rus) to Dublin, where he appointed his son as king of Leinster and Dublin. This was Conchobar, whom Toirrdelbach favoured above his better- known son Ruaidri, the future king of Ireland, but who met an early death in 1144. Conchobar, had little hope of making good the claim to Leinster – his father was merely playing politics here. The object of the exercise was to stamp Connacht’s control on Dublin, and its significance cannot be overstated: Toirrdelbach Ua Conchobair was the fourth successive claimant to the kingship of Ireland to install his intended heir as king of Dublin. Young Conchobar, however, was ejected from Dublin within a year, and thereafter his father exercised only a fitful control over the government of the city-state. In the early 1140s his major rival for power in Ireland was Conchobar Ua Briain, a nephew of Muirchertach M6r, who launched an invasion of Connacht in 1141. The interesting thing, though, is that Ua Briain initiated the invasion by first of all marching from north Munster to Dublin and accepting the kingship of the city from the Ostmen. The pattern of former years therefore repeats itself. Conchobar Ua Briain of Munster aspired to be king of Ireland. Toirrdelbach Ua Conchobair of Connacht currently held that position. King Toirrdelbach’s reign was not ended when the Ostmen transferred the kingship of their city to Ua Briain (co dtugsat Coill a rfghe dh6) , but the event was heavily laden with Significance, and the implications for Ua Conchobair were severe.

Diarmait Mac Murrough from the margins of a late

edition of the account of Giraldis Cambrensis.

Islesmen in Dublin

Unfortunately for Munster’s hopes of making a comeback in Dublin, Conchobar Ua Briain died within a year. And because King Toirrdelbach had more than enough distractions elsewhere, the control of Dublin slipped temporarily out of Irish hands. Just as Godred Crovan and Magnus Barelegs, having established a powerbase in the Isles, had then launched an assault on Dublin, so now, in 1142, the same thing happened again. Dublin was seized by a Manx or Hebridean sealord called Ottar, who successfully managed to reign over the city for a full six years, until the Meic Turcaill, an Ostman family who had risen to prominence in Dublin and Fine Gall in the twelfth century, had him assassinated in 1148. Although Ottar’s reign over Dublin was simply a brief interlude in an otherwise continuous Irish dominance, it did serve to reinforce the point that the City-state, because of the attractions it offered in terms of its wealth and its cosmopolitan mix, was always likely to fall prey to external aggression. Ottar’s regime demonstrated also that, although Dublin and the Isles seem to have had separate kings for the previous thirty years or so, the two kingdoms were dominated by an oligarchy with a foot in both camps, whose leader was likely to take advantage of favourable circumstances to try to reunite them. This was to happen on two further occasions in the mid-twelfth century. The king of the Isles for most of the first half of the twelfth century was Godred Crovan’s son Amlaib. According to the Chronicle of the Kings of Man, he was murdered in or around 1 152 by an army that invaded the Isle of Man from Dublin, led by his nephews who had been reared in the city. They then divided the island between them and even attempted to gain control of Galloway. In this, though, they were unsuccessful, and they lost Man too when Amlaib’s son Gofraid returned from Norway, was proclaimed king by the Manx, and had the ringleaders of the Dublin army executed. Once settled in as king of Man and the Isles, Gofraid sought to repeat the success of his grandfather Godred Crovan in adding Dublin to his little empire. If the Chronicle is to be believed, the Dubliners, apparently dissatisfied with continued Irish overlordship, sent for Gofraid to rule over them. He assembled a fleet, sailed to Dublin, and was received by the citizens with much dancing and rejoicing, and proclaimed king by common consent.

Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn

The problem for Gofraid was that the new king of Ireland, Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn of Ailech, was not prepared to accept this flouting of his overlordship. In 1 154 Mac Lochlainn had paraded his new dominance over the Irish political landscape by leading his armies triumphantly over Connacht and Breifne, eventually coming as far as Dublin, where the Dubliners submitted to him as king. There, as a sign that they were now his vassals, he granted them tuarastal or wages in the form of 1,200 cows. This brought the Dubliners back into line. These events took place in 1 162. Although Mac Lochlainn of Ailech was ultimately their overlord, over the next few years, until the Ostmen rebelled at Mac Lochlainn’s death in 1 166, Diarmait Mac Murchada was the real master of Dublin. He was not without justification in claiming such an honour. His great-grandfather, vate his favourite son to the kingship of Dublin. In so doing, he caused a minor revolution in Irish politics. It cannot be a coincidence that over the next seventy-five years, each of the three successful claimants to the kingship of Ireland emulated him and appointed their intended heirs to rule Dublin. The conclusion seems inescapable: to assume the high-kingship it was necessary to gain control of Dublin. But if to rule Ireland one needed to rule Dublin, it was for more than pragmatic reasons. More was involved than the exploitation of its military resources or its wealth. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the status of Dublin in the Irish polity grew apace. While the kingship of Tara had held (or was believed by contemporaries to have held) a special place in the Irish body politic, the myth became hard to square with reality when the province of Mide lost . its former greatness, and Tara became the scene of petty local squabbles. At the same time, Dublin rose in importance both economically and symbolically. Thus, when Ruaidri Ua Conchobair of Connacht made his bid for the high-kingship in the summer of 1 166, the account in the annals of how he went about doing so is very revealing: he led his armies to Dublin and ‘was there inaugurated as honourably as any king of the Gaidil was ever inaugurated’. We are not told in so many words what kingship it was that Ruaidri had assumed. Technically, he was making himself master of Dublin. In practice, in the very act of so doing, he was staking his claim to the kingship of Ireland. Diarmait Mac Murrough from the margins of a late edition of the account of Giraldis Cambrensis. was an enormous sum and it shows that any would-be Irish master of Dublin would henceforth have to pay dearly for their loyalty. Clearly, though, for the aspiring king of Ireland it was a price worth paying. Having done so, however, he was not prepared meekly to allow them defect to Gofraid’s banner. Mac Lochlainn led a vast army to Fine Gall and some confused fighting followed. Though neither side was victorious, Gofraid was eventually persuaded to withdraw, and Mac Lochlainn’s ally, Diarmait Mac Murchada of Leinster, Diarmait mac Mail na mB6, had been the first Irish king to overthrow the reigning Ostman dynasty and assume its kingship himself. Dublin and the high-kingship In pursuance of his ambition of outmanoeuvering his rivals for the kingship of Ireland, King Diarmait mac Mail na mB6 had proceeded to ele-

Sean Duffy lectures in medieval Irish history in Trinity College, Dublin.

Further reading: A. Candon, ‘Muirchertach Ua Briain, politics, and naval activity in the Irish Sea 1075 to 1 1 19’, in G. Mac Niocaill et al (eds.), Keimelia (Galway 1988). S. Duffy, ‘Irishmen and Islesmen in the kingdoms of Dublin and Man, 1052- 1 17 1’, in Eriu, 43 ( 1992). D. 6 Corrain, Ireland before the Normans (Dublin 1972).

Toirrdelbach ua Briain

Toirrdelbach ua Briain next forty years, came to dominate the Irish political scene. But Dublin was where ‘_ . ISLE!) OF MAN he served his apprenticeship and Dublin remained central to his strategic considerations throughout his career. During his father’s lifetime, Muirchertach used the forces of Dublin to invade the ailing province of Mide (Meath), and to overcome opposition to his father’s overlordship by Ua Ruairc of Breifne. Also, as early as 1073, within a year of Munster gaining control of Dublin,two members of the Ui Briain were killed in the Isle of Man. In gaining power in Dublin, they were keen to assert their dominance in the Irish Sea region as a whole, like the Leinstermen before them. That dominance may have receded temporarily following the death of Toirrdelbach ua Briain in 1086. A contest for the succession to Munster broke out between his sons and it was a number of years before Muirchertach M6r, having quelled his rivals’ dissidence, settled into the kingship and set about regaining mastery over the rest of the country. In the interval, a remarkable change had taken place in the government of Dublin. Just as the kings of Leinster and Munster had attempted, in seizing Dublin, to gain possession of its Irish Sea satellites, so the reverse now occured, and not for the last time: while Ua Briain’s back was turned, Dublin and Fine Gall were annexed by an ambitious warlord from the Isles.

next forty years, came to dominate the Irish political scene. But Dublin was where ‘_ . ISLE!) OF MAN he served his apprenticeship and Dublin remained central to his strategic considerations throughout his career. During his father’s lifetime, Muirchertach used the forces of Dublin to invade the ailing province of Mide (Meath), and to overcome opposition to his father’s overlordship by Ua Ruairc of Breifne. Also, as early as 1073, within a year of Munster gaining control of Dublin,two members of the Ui Briain were killed in the Isle of Man. In gaining power in Dublin, they were keen to assert their dominance in the Irish Sea region as a whole, like the Leinstermen before them. That dominance may have receded temporarily following the death of Toirrdelbach ua Briain in 1086. A contest for the succession to Munster broke out between his sons and it was a number of years before Muirchertach M6r, having quelled his rivals’ dissidence, settled into the kingship and set about regaining mastery over the rest of the country. In the interval, a remarkable change had taken place in the government of Dublin. Just as the kings of Leinster and Munster had attempted, in seizing Dublin, to gain possession of its Irish Sea satellites, so the reverse now occured, and not for the last time: while Ua Briain’s back was turned, Dublin and Fine Gall were annexed by an ambitious warlord from the Isles.