Pinochet and me

Published in 20th-century / Contemporary History, Features, Issue 4 (Jul/Aug 2008), Volume 16

Pinochet in the 1990s.

The fear of embarrassment, a comrade from my Workers’ Party days once told me, is stronger than the fear of death. He knew what he was talking about. The INLA had threatened to kill him, and the threat was very acute on a particular Saturday night. It happened to be a night when he and his wife were giving an important dinner party for professional colleagues, to whom such matters could not be mentioned, much less explained. During the dinner, his wife gave him their pre-arranged signal to make himself scarce—a red alert, you might say. Going to the kitchen, she had seen a car filled with burly men parking outside their house. She then went out to confront the enemy alone, with only her apron for body armour. (This couple had bravely consistently refused on principle to accept the protection on offer from the party’s ‘military wing’, of which they were not members.) It turned out that the men were simply looking for another house, but when she returned she found her husband still chatting away to their guests. When their oblivious guests finally departed, she vented her fury. Why, she demanded, had he not followed their meticulous if implausible plan, and rolled through the open window behind him to the relative safety of their shrubbery? Because, he told her, he had had this epiphany about the balance of fear between embarrassment and death.

Happily, the days when one might have feared death in writing an article about Irish paramilitary groups and their pervasive relationship to our politics are now long gone. But the fear of embarrassment remains. I do find it more than a tad awkward to attempt an explanation of how the world looked to young leftists like myself in the early 1970s. This was a time when incidents like the one just described did not seem very exceptional in the world I lived in. It was a world where Sam Beckett was co-writing our scripts with Bertolt Brecht. But I am all too aware that for many younger readers my former world-view will just seem silly, not absurd; and crazy, not committed. But it didn’t seem like that at the time.

I blame General Pinochet for getting me mixed up in this kind of thing. Why? Well, you have to understand that in the 1970s the world, as I and many other people saw it, was divided into two great camps, imperialist and socialist. The imperialists were raping Vietnam, ravaging Mozambique and Angola, and funding the agents of apartheid in South Africa. They also backed the bigoted Stormont regime in Northern Ireland. Mind you, this last bit was complicated—things closer to home always are. While the British imperialists backed the loyalists, the American imperialists were backing the Provos, or so my Marxist political mentors in Official Sinn Féin (precursor of the Workers’ Party) told me

But back to Pinochet: I had shared a broadly socialist world-view for a number of years, but I was far from convinced that workers behind the Iron Curtain lived in paradise. I knew about the show trials, the gulags and the famines. I thought that things were better in the liberated zones of Vietnam, and especially of Mozambique and Angola—for I had read Basil Davidson. I was also seduced by Jim Fitzpatrick’s poster of Che. To be fair to myself, this Caribbean infatuation had some basis in reality: Cuba blended tough anti-imperialism with good schools and a great health service, and still managed to be laid-back, sexy and young. It seemed a fine model for Latin America, and possibly for Ireland as well.

And yet, and yet . . . I balked at Castro’s embrace of the dictatorship of the proletariat, which was visibly morphing into the dictatorship, however benevolent, of the great man himself. Surely, I thought, it was possible, at least in Europe, to build socialism through a broad democratic movement, preserving our hard-won liberties of free expression and free assembly alongside the new social and economic liberties we leftists were pursuing? The thinking of ‘euro-communists’ in France, Spain and Italy looked attractive. But no-one in Ireland seemed to have a handle on that combination at the time. Among Irish left-wing groups, only Official Sinn Féin had firm but practical socialist policies, as I saw things, anyhow. It was also ploughing a relatively honourable furrow in the sectarian morass of Northern Ireland at the start of the Troubles. The party stood in two shadows, however: the increasingly dogmatic loyalty of its leadership to the Soviet Union; and the highly influential presence within both leadership and rank-and-file of a ‘military wing’, the Official IRA. (The existence of the latter was known to the very dumbest of street-dwelling canines at the time, yet many ex-Official Sinn Féin/Workers’ Party members, especially some of those prominent in today’s Labour Party, seem to have been blissfully unaware of the gunmen and women with whom they licked envelopes and put up posters.)

‘I blame General Pinochet for getting me mixed up in this kind of thing’—pictured here with other members of the junta just after the September 1973 coup. (Guardian

I had several discussions about joining Official Sinn Féin with party members in the early 1970s. They were friendly enough, but dismissive of my squeamish approach to the hard realities of taking state power for a ‘serious’—we were all very serious in those days—left-wing organisation. Give us a single example, they would say, of a genuinely socialist, or even leftist, government that has been democratically elected and that imperialism has not overthrown, or tried to overthrow, by force of arms? And indeed, when they listed the monsters propped up by Washington and London as bulwarks against ‘communism’—Somoza in Nicaragua, Franco in Spain, the Shah in Iran, Suharto in Indonesia, Vorster in South Africa—the argument was hard to counter.

But I still had one card with which to resist my Stalinist seducers. Salvador Allende, a left-wing social democrat, supported by a communist party at least nominally committed to parliamentary democracy, had won an open election in Chile in 1970. He was leading that country towards socialism in the full light of democratic freedoms. He was beginning to rival Castro as a beacon for the young international left, and the social advances in his country were remarkable. Santiago was looking daily like a better place for its working people than Havana, and infinitely better than Moscow. The balance of power in the world had shifted, and the broad and open parliamentary road to socialism was the way forward from now on, or so I naively thought.

Then, on 11 September 1973, that fragile hope collapsed as Pinochet’s jets bombed the presidential palace, and Allende was murdered or committed suicide. US support for the coup, since confirmed by, ironically, America’s own very democratic freedom of information procedures, seemed obvious. Pinochet, whom Margaret Thatcher would later describe as a ‘Christian gentleman who saved Chile for democracy’, immediately imposed savage repression on all democrats. The police could murder you for having a trade union card, or put a rat up your vagina to extract information about leftists who escaped the first round-up.

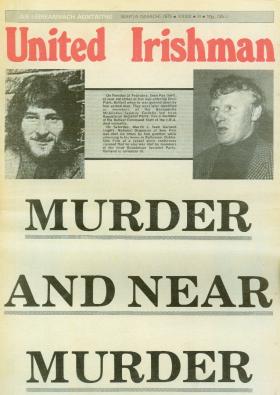

‘Within a year of joining the party, the movement split and the Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP) and the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) emerged. The subsequent feud between the Official IRA and the INLA seemed more like a vendetta than an ideological conflict.’ (The Workers’ Party)

I was devastated. I had no arguments left against the blandishments of my Marxist-Leninist friends. I was in Paris at the time, and marched with tens of thousands of protestors chanting ‘Pinochet, assassin, Pompidou complice!’ We saw no difference any more between democratically elected western leaders and the dictators whom they—disgracefully, I still believe—supported. Democracy was a sham, it seemed, and when the chips were down, political power really did come from the barrel of a gun. I still cannot fully explain to myself why the rather more blatant, if less bloody, suppression of democratic socialism by the Soviet Union in Czechoslovakia five years earlier did not give me pause in my ideological pilgrimage.

A few months later I joined Official Sinn Féin, and though I never joined its military wing—cowardice may have been my saving grace—for a period I believed that it was a vital element in ‘the movement’, which had to be supported. I am not proud of that now, but that is what I thought at the time. Only one friend ever challenged me about what I was doing. ‘I am sorry,’ he said, ‘that you have joined an organisation that endorses the death penalty.’ I told him he was wearing petit bourgeois blinkers against harsh reality, but that I was sure he would see the error of his ways before long. Now I just wish I had had his clarity of vision.

At the start, whenever any doubts arose, my broken argument about Chile came back to haunt me like a sharp intellectual boomerang. Meanwhile, Chilean supporters of Allende found refuge in Ireland, and attended our party rallies and played haunting music at our social events. Their grim stories were a constant reminder that, even in a long-established democracy like Chile, the price of unarmed socialism could still be death, torture and exile.

Soon, however, I began to realise that the presence of a military wing close to a political party, at least under democratic conditions, is more of a millstone than a guarantee of security. Within a year of joining the party the movement split, and the Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP) and the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) emerged. The subsequent feud between the Official IRA and the INLA seemed more like a vendetta than an ideological conflict.

At the time, I happened to be living in Wicklow, home territory of Seamus Costello, the INLA’s founder and first leader, who had previously represented Official Sinn Féin locally as a very effective county councillor. He and his people came to attend public meetings we had called on nationalising industries related to minerals, oil and gas. We were under instructions to set up a ‘broad front’ (ah, those weasel words) called the Resources Protection Campaign. We had little alternative but to let Costello and his comrades in—there were, after all, more of them than us. But some of us also believed that it would be undemocratic to exclude them from public debate. Perhaps we were closet social democrats all along, though we would not have admitted it at the time.

I was summoned to Gardiner Place, head office of Official Sinn Féin, to account for our scandalously ‘liberal’ and ‘undisciplined’ behaviour. I was faced with a party leader who was also a very senior Official IRA officer, and a roomful of glowering strangers. Rather apprehensively, I recited our position, from both the pragmatic and the principled angles. And again, Pinochet found a place in the room. ‘You see’, said the party leader, ‘there are people like you, who don’t want to take the necessary steps to defend your organisation, which is the only defence of the working class. What you don’t realise is, you will be taken to the stadium with the rest of us if there is a counter-revolution here, and then it will be too late for you, won’t it?’ The ‘stadium’ was the football ground in Santiago where leftists were held prior to torture and execution immediately after Pinochet’s coup. It had become a universal symbol of right-wing state terrorism. What he was saying must have been repeated by hard-left parties all over the world. Not for the first time, the terrorism of the Right was being used to justify recourse to ‘armed struggle’ by the Left.

‘We were under instructions to set up a “broad front” called the Resources Protection Campaign.’ (The Workers’ Party)

I have no doubt that this leader sincerely believed what he was saying, and that he and the men who laughed with him at his gallows humour were comfortable in the Manichean world we were all part of, where lines were clearly drawn. Gradually, however, I began to feel increasingly uneasy, as the lines looked less and less clear-cut to me. An incident in which an ideological disagreement was resolved not by the political organisation but by a kind of paramilitary court disturbed me deeply. As I learned what a terrifyingly shambolic organisation our exemplary ‘people’s army’ really was, I confided in a comrade I trusted that I was horrified. ‘I always thought’, I told her, ‘that our military wing would be like the NLF in Vietnam.’ She was a little older than I was, and a lot wiser. ‘Has it never struck you’, she asked me wearily, ‘that the NLF in Vietnam may in fact be very like our military wing?’

Not very long afterwards I left the party, and the comfortable certainties it had offered me, in the rather appropriate year of 1984. In fairness to the party, which was taking a euro-communist tack before splitting between Stalinist/militarist and social-democratic factions, I was later allowed to publish a critique of Stalinism and (implicitly) militarism, ‘On the Outside, Looking In’, in the party journal, Making Sense (Jan./Feb. 1991). Luckily for all of us, we were indeed living in a democratic republic, however flawed, and not in one of the recently defunct ‘socialist’ countries that some party leaders still eulogised at the time.

The world has looked a lot more confusing ever since I abandoned the ideological comfort zone of dogmatic Marxism. But confusion, as Brian Friel memorably put it in Translations, is not necessarily an ignoble condition. And whatever clarity I have left tells me that, while Pinochet was a vile tyrant, and the coup was a terrible blot on the foreign policy of a great democracy, you should be very careful before you draw too many conclusions from things that happen half a world away.

Paddy Woodworth is author of Dirty war, c lean hands (Yale University Press, 2003) and The Basque Country: a cultural history (Signal Books, 2007).

lean hands (Yale University Press, 2003) and The Basque Country: a cultural history (Signal Books, 2007).