Piety, patrons and prints: Franciscan altar plate, 1600–1650

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Issue 3 (May/Jun 2008), Volume 16

Angels’ heads appeared on both chalices and monstrances, such as this 1664 James Fitzsymon monstrance from Dublin. (National Museum of Ireland)

At a meeting held in Dublin on 15 February 1698, the superiors of the Franciscan Order agreed to adhere to the act of banishment issued a few months earlier, ordering Catholic religious orders out of the country. The third point on the agenda was the question of material goods belonging to the friars. It was decided that these were to be handed over for safekeeping to the patrons of the friaries. Each person receiving such goods was to sign a document detailing the items they had received. A separate inventory was to be made of all the goods from each friary prior to their dispatch. The surviving inventories from Kilconnell and Meelick (Co. Galway), Killeigh (Co. Offaly) and Donegal provide us with a glimpse of the wealth of altar plate once held by these friaries. They also highlight the strength of patronage and the close relationship between the friars and the local community. The documents stand as witnesses to objects that are now lost: of the 70 items listed, only seven can now be securely identified. Despite the low survival rate of the artefacts, a significant number of objects associated with the Franciscans and other mendicant orders have survived and have recently been recorded for an important research project into the material culture of these orders in late medieval and early modern Ireland. The number, quality and range of portable artefacts pre-dating Catholic Emancipation listed so far are astonishing. The types of objects comprise altar plate such as silver and pewter chalices, silver and pewter patens, monstrances and crucifixes. Other church furnishings include processional crosses, ciboria, thuribles, sanctuary lamps, candlesticks, reliquaries, pyxes, bells and paxes. Two distinctive groups of object types encompass liturgical vestments and statues. Amongst small objects recorded are pendant crosses, rosaries and seals. These objects shed light on the role of the mendicant orders, both male and female, in preserving an important aspect of an Irish visual culture.

Chalices and their style

Most historical artefacts pre-dating 1829 associated with the Irish Franciscans were produced between 1600 and 1650, a period of intense intellectual activity for the Irish Franciscans on the Continent, following the foundation of colleges in Louvain (Low Countries), Rome (Italy), Prague (Bohemia), Capranica (Italy), Boulay (Lorraine) and, for a short time, in Wielun (Poland), as well as being a period of strong patronage of the Franciscans in Ireland. Amongst the artefacts the largest group consists of silver chalices. The information provided by each object, such as stylistic features, inscriptions and details of imagery, makes them important pieces of evidence that can not only be viewed and admired for their artistic achievement but can also be read as historical documents. Even though a system of hallmarking had been introduced into Dublin in 1637, the majority of the Catholic pieces were not hallmarked but are often inscribed with the date and the name of the benefactor, as well as the name of the friary to which the piece was donated.

Franciscan altar plate demonstrates a high level of craftsmanship amongst Irish silversmiths. Regional styles can be distinguished for chalices produced between 1600 and 1650. These styles, represented by objects associated with Cork, Dublin, Galway (Pl. 1), Kilkenny, Limerick and Waterford, bear their own characteristics and are testimony to a thriving craft of silversmithing. After 1650 the Baroque style featured more frequently, as opposed to the Late Gothic style of the pre-1650 objects, and the regional styles became less evident. Chalices had a domed or a multi-lobed foot and a baluster stem. Angels’ heads appeared on both chalices and monstrances of the time (Pl. 2). While the Baroque style continued to be employed on some eighteenth-century pieces, the majority of chalices from that period became smaller and simpler in design, probably mirroring a weakened patronage.

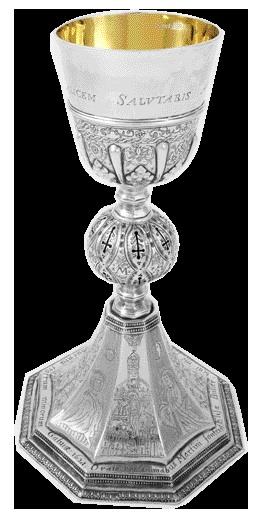

Some seventeenth-century Galway chalices, such as the 1621 Martin Font and Eliza Butler chalice here, present (on the base or foot) a complex image of the Mercy Seat, consisting of the image of the Holy Trinity combined with the Crucifixion. (National Museum of Ireland)

The Cross, St Francis and the Virgin Mary

The iconography of the altar plate is firmly rooted in Franciscan spirituality and focuses on three main themes: the Cross, St Francis and the Virgin Mary, devotion to all of which was promoted by the Order and is manifest in the earliest Continental artwork associated with it. The depictions of the Cross are varied: some chalices display simple

Crosses while some bear images of the Tree of Life, where foliate scrolls sprout either from the Cross or next to the Cross. Yet others are engraved with the Crucifixion, or the Cross accompanied by the Instruments of the Passion (Pl. 3). At times Christ on the Cross is flanked by the figures of the Virgin Mary and John the Evangelist. Finally, some seventeenth-century Galway chalices present a complex image of the Mercy Seat, consisting of the image of the Holy Trinity combined with the Crucifixion (Pl. 1).

Prints and the transmission of visual ideas

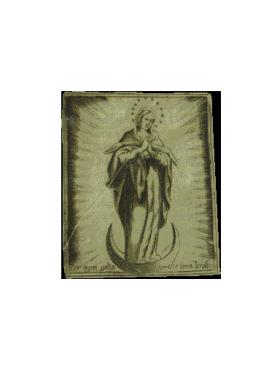

The image of the Immaculate Conception represented on the Anastasia Rice chalice (Pl. 5) was of a relatively recent origin. The very fact that it features on a Franciscan object shows that the Irish Franciscans, their benefactors and artists were well aware of new Counter-Reformation ideas coming from a Baroque-steeped Europe. The image of the Immaculate Conception depicted by the greatest painters of the time, such as Rubens, El Greco and Zurbaran, had been popularised by Flemish printmakers, including the Wierix family, whose prints illustrate books that form part of the Irish Franciscan book heritage now held in the UCD Special Collections. The image also opens Andrea Cirino’s De urbe Roma, published in Palermo in 1665, a copy of which is now in UCD. Such books exemplify the type of visual culture available to the Irish Franciscans on the Continent (Pl. 6).

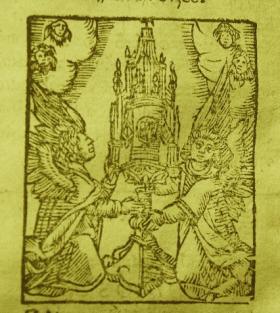

A similar multi-tiered monstrance features in Antoin Gearnoin’s Paradise of the Soul (Louvain, 1645). (National Museum of Ireland and UCD-OFM Partnership)

Portable single prints and illustrated books may also have been responsible for the iconography

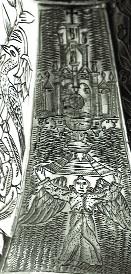

of other representations on the chalices. The depiction of an angel holding a monstrance on the Font–Butler chalice also points towards Germany and the Low Countries as possible sources of visual influence. The monstrance is of a cylinder type, a shape common in those countries from late medieval times (Pl. 7). A multi-tiered monstrance surmounted by a cross and supported by two angels features in Antoin Gearnoin’s Paradise of the Soul, published in Louvain in 1645. This image is quite similar to that on the Galway chalice, suggesting that similar exemplars underlie the design in the book and on the chalice (Pl. 8).

The depiction of the Mercy Seat on the Anastasia Rice chalice, on the other hand, is somewhat suggestive of Albrecht Dürer’s 1511 print depicting the Holy Trinity. Dürer’s prints were definitely used as sources for imagery on English recusant silver, and while the Irish Franciscans would have been exposed to liturgical objects produced on the Continent, the actual iconography for chalices made in Ireland might have been transmitted to Irish silversmiths through printed material.

Patrons

The Latin phrase ‘me fieri fecit’ or ‘me fieri fecerunt’—‘caused me to be made’—is often engraved after the donor’s name on the foot of a chalice, a ciborium or a monstrance. The donors commemorated on the Franciscan altar plate were in most cases either members of the Franciscan Order or lay benefactors closely associated with the Order. Amongst the latter were prominent merchants and landowners of the period, whose family members frequently held important positions as provincials, guardians or confessors of the Order. Women were also important patrons of the Franciscans and their names are often found on the chalices. Some, such as Anastasia Rice, belonged to the Third Order of St Francis. Interestingly, chalices associated with female donors often bear a representation of the Virgin Mary. Names of benefactors include both Irish and Old English names. Ecclesiastical silver associated with the rural Gaelic friaries usually carries Irish names, while the Old English names tend to feature on silver donated to the friaries in the towns of Cork, Dublin, Galway and Limerick.

An exhibition entitled Franciscan Faith: Sacred Art in Ireland 1600–1750 currently running in the National Museum of Ireland, Collins Barracks, based on the research done on the Franciscan material, celebrates the great achievement of that Order in creating and preserving precious artwork throughout the periods of political uncertainty of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. What survives is probably a mere ten per cent of what was once in the possession of the friaries and is a testament to the care of the people who believed in the value of liturgical objects.

The depiction of an angel holding a cylinder monstrance on the Font–Butler chalice also points towards Germany and the Low Countries as possible sources of visual influence.

Margorzata Krasnodebska-D’Aughton is an IRCHSS Research Fellow at the UCD Mícheál Ó Cléirigh Institute.

Further reading:

J. R. Bowen and C. O’Brien (eds), A celebration of Limerick’s silver (Cork, 2007).

J. J. Buckley, Some Irish altar plate (Dublin, 1943).

I. Delamer and C. O’Brien (eds), 500 years of Irish silver (Dublin, 2005).

R. Moss, C. N. Ó Clabaigh and S. Ryan (eds), Art and devotion in late medieval Ireland (Dublin, 2006).

C. Oman, English engraved silver 1150 to 1900 (London and Boston, 1978).¡

The image of the Immaculate Conception that opens Andrea Cirino’s De urbe Roma (Palermo, 1665). Such books exemplify the type of visual culture available to Irish Franciscans on the Continent. (UCD-OFM Partnership)