Physical force or passive resistance?

Published in Issue 2 (March/April 2019), Platform, Revolutionary Period 1912-23, Volume 27Soloheadbeg—vindicating a democratic mandate for independence.

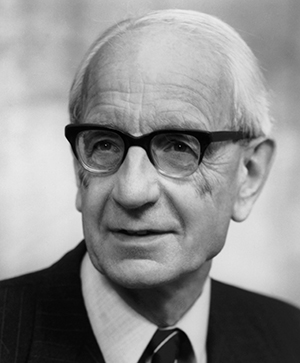

By Martin Mansergh

‘History was forged in sudden death on a Tipperary byroad as surely as it ever was in meetings at Downing Street or for that matter at the Mansion House in Dublin, where the Dáil met coincidentally but fortuitously that same day, 21 January 1919.’

So wrote historian Nicholas Mansergh, my father, who was eight years old at the time of the incident, from a landed family and living two miles away, about the Soloheadbeg ambush, in which two RIC constables escorting a horse-drawn consignment of gelignite to a quarry were killed after being suddenly confronted by a group of Volunteers who had been waiting for days behind a hedge to capture it. This freelance action occurred on the same day as the inaugural meeting of Dáil Éireann in Dublin’s Mansion House. It is a salutary reminder that history is made from below as well as from above, which perhaps accounts for the lingering metropolitan resentment of it.

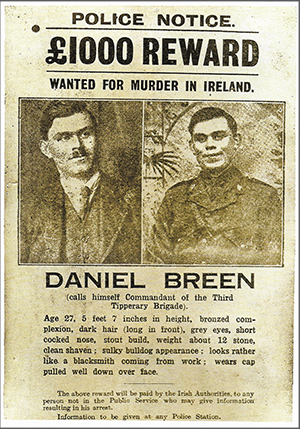

The resonance of the ambush was greatly enhanced by the coincidence of timing but also by the shock and controversy caused by the shooting of two inoffensive RIC constables. Indeed, one of them in conversation a few weeks previously had discounted the likelihood of becoming a target. The ambush was highlighted in one of the earliest accounts of the War of Independence, Dan Breen’s My fight for Irish freedom (first published in 1924), and it has provided a good starting-point for those wanting to question the morality of the whole war.

There are also those coming from other directions who want to question whether the ambush at Soloheadbeg was the start of hostilities. Of course, the definition of a conflict or any named period in history is as much a matter of convention as a question of fact. The case for Soloheadbeg representing the start of the War of Independence rests on the fact that, unlike earlier clashes, it took place after the people voted for independence in the December 1918 general election and on the day that the Dáil, meeting for the first time, issued a Declaration of Independence, even if the ambush happened a few hours previously. Attacks on police and police barracks were to become much more frequent. Sometimes it was Volunteers who lay dead afterwards rather than policemen, as was the case in a raid for arms on a Kerry barracks in April 1918.

To accept that the Soloheadbeg ambush represented the start of the War of Independence is not quite the same thing as saying that it started it. While Dan Breen claimed that Seán Treacy and he wanted to start a war by killing as many policemen as possible, other participants in the ambush did not accept that the killings were deliberate and premeditated, at least on their parts, though all armed actions carried the risk of fatalities on either side. At first, the ambush seemed an isolated incident. It was followed in May by the dramatic rescue of one participant, Seán Hogan, who had been taken prisoner, off the Dublin–Cork train at Knocklong, which saw two policemen and one Volunteer shot dead and others wounded in a shoot-out. Intensification of the conflict started later, however.

Notwithstanding disapproval at leadership level within the independence movement, the ambush took place within a context where the tone had become increasingly bellicose. The Declaration of Independence passed at the Dáil’s first meeting was more polemical and less high-minded than the 1916 Proclamation.

The Dáil’s ‘Message to the Free Nations of the World’ spoke of ‘the existing state of war, between Ireland and England’. Whether this referred back to the conscription crisis, the last few years since the Rising, the last few centuries or to everything since 1171 is unclear. The 1918 Sinn Féin election manifesto, echoing the Ulster Covenant, pledged ‘making use of any and every means available to render impotent the power of England to hold Ireland in subjection by military force or otherwise’. It is very difficult to argue that the ambush or its outcome was in contradiction with the position of Sinn Féin or the Dáil at the level of principle, as opposed to the opportuneness of its timing and tactics.

The O/C at the ambush, Seumas Robinson, did take issue with a faction in Sinn Féin headed by Arthur Griffith, who believed that ‘a united passive resistance was all-sufficient [my emphasis] to win our independence’, a noble method now associated with Gandhi but only likely to work, if at all, where a large population can be mustered behind it.

One of the challenges facing commemoration of the period from January 1919 to the Truce on 11 July 1921 will be balancing the weighting of the armed conflict versus political and constitutional developments. For the independence struggle to succeed, it needed a strong case to be made to the world. Robinson, author of a reflective witness statement, conceded that ‘without a strong, vigorous, and vociferous political party the Army would be swamped by pro-British propaganda of press and pulpit’. They could ‘see the usefulness, the importance, the necessity of the moral-legal support of an elected Government’, and were ‘sensible to the necessity of having the will of the people behind the coming struggle’. But the Dáil also needed Volunteers willing and able to fight for independence and, if necessary, to sacrifice their lives and those of others.

A lot of historical commentary has been much too binary, pitching constitutionalism against armed action, as if they were sharp opposites. The three directors of the IRA campaign, Michael Collins, Richard Mulcahy and Cathal Brugha, were all TDs, and ministers some or all of the time. After the Dáil’s suppression in September 1920, it met only eight times before the Truce in July 1921, though departments and republican courts functioned during the period.

Outside of the Black and Tans and the Auxiliaries, or in the north the Specials, the response of the British Empire is not subjected to as much critical scrutiny or measured against any moral compass. Before and after the 1918 general election, and even long after the ‘concession’ of the Irish Free State, the idea that Ireland could become a fully sovereign, independent state was repeatedly ruled out. A First World War general of Anglo-Irish background, Lord French, was made viceroy and advised by an obtuse unionist cabinet minister in charge of its Irish committee, Walter Long. The 1918 election in Ireland was anything but free and fair, with half of Sinn Féin’s successful candidates interned. The British government simply ignored the result. The Church of Ireland Gazette in its 27 December 1918 issue was more prescient than it knew, when it commented on the Sinn Féin members’ pledge of abstention from Westminster: ‘Without the sanction of force, such a policy is nothing short of suicide’. Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa had been right when he stated that the Irish ‘needed to show England that she is losing more than she is gaining by holding us’. That was what the political and military struggle for independence was all about. The primacy of the Dáil and the accountability to it of the army took longer to establish, and not at the first attempt.

Martin Mansergh is a former government adviser and politician.