Penal days in Clogher

Published in Early Modern History (1500–1700), Features, Issue 3 (May/Jun 2009), Penal Laws, Volume 17, Williamite Wars

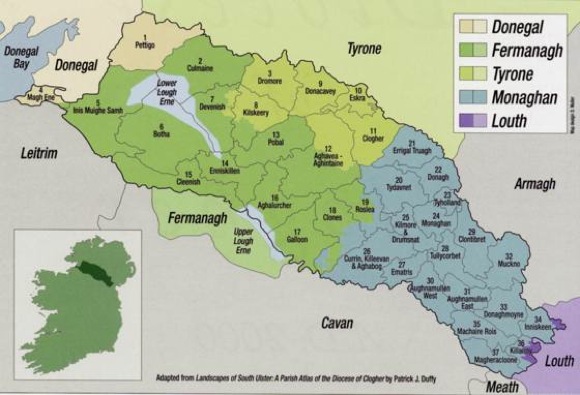

In July 1704 Clogher diocese had seventeen priests registered in County Monaghan, eleven in Fermanagh, four in Tyrone and one in Louth.

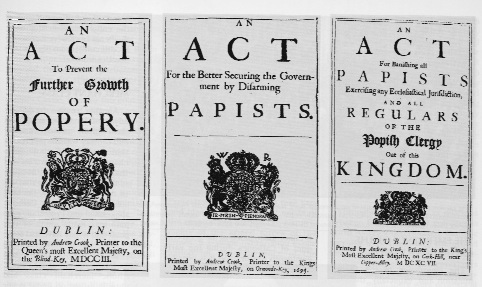

In the aftermath of the Williamite revolution religious persecution intensified. In 1697 the Irish parliament, an exclusively Protestant assembly since 1691, enacted a law to banish all Catholic bishops and others exercising ecclesiastical jurisdictions, as well as regulars (religious orders), from Ireland. In 1704 ‘an act to prevent the further growth of popery’ demanded the registration of Catholic priests. Only one priest could be registered for each civil parish; all others were obliged to leave the country.

Registration offered a degree of toleration to priests in the parish for which they were specifically registered but to none other. It was to provide a baseline for the gradual elimination of the institutional Catholic Church in Ireland. With no bishops permitted under the terms of the Banishment Act, no priests allowed into Ireland from overseas, and no priest allowed to minister except for those registered in 1704, the Irish Catholic priesthood would die out over time and not be replaced. A comprehensive register of priests was drawn up, and a renewed drive was made against Catholic bishops. In 1706 the only Catholic bishops in Ireland were the incapacitated archbishop of Cashel and the imprisoned bishop of Dromore. The future prospects for the Catholic Church in Ireland seemed bleak indeed.

Clogher diocese in 1704

In July 1704 Clogher diocese had seventeen priests registered in County Monaghan, eleven in Fermanagh, four in Tyrone and one in Louth. Not all parishes had their own priest; in several instances a priest was registered for two parishes combined. None of the priests registered in 1704 had been ordained since the Williamite revolution. Their average age was 54 years and six months, but 72 per cent of them were aged 55 or older. Given the lower life expectancy prevailing in the early eighteenth century, the registered priests could be expected to die out within a generation.

Significantly, none of the Clogher priests had been ordained outside Ireland, reflecting the general poverty of the Catholic community across Ulster. In County Monaghan there were some Catholics who could afford to offer sureties of £50 for their priests to be registered. Tellingly, there were no sureties for the priests registered in the Ulster plantation parishes. Only one of the registered priests, Art McQuillin, parish priest of Templecarne, was a regular cleric; he was the prior of the Franciscan community on Lough Derg in 1714.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

What was the purpose of the penal laws?

Maureen Wall argued that the penal laws were not intended to exterminate Catholicism but to neutralise the political threat that the Catholic community might pose to the Protestant ascendancy. On the other hand, S. J. Connolly has argued (more persuasively in my view) that the purpose of the ‘popery laws’ was to eliminate Catholicism from Ireland. That the legislation failed was due in part to the remarkable tenacity of the Catholic clergy and laity, but also to the problems that the state encountered in enforcing its draconian code over a prolonged period while sectarian passions waxed and waned. The Protestant ascendancy may have settled eventually for using the penal code simply to bolster its power and privileges, but the initial intention to eradicate Catholicism was very real.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Dr Hugh MacMahon was appointed bishop of Clogher on 22 March 1707. Born in 1660, he obtained a doctorate in divinity from the Irish College in Rome in 1689. His intention to return to Ireland was thwarted by the Williamite revolution, and he spent the next six years studying in Brussels. In 1696 he became a canon of St Peter’s College at Cassel in the diocese of Ypres. Early in 1701 he was appointed vicar-general of Clogher, though the Banishment Act prevented him from returning to Ireland. After his consecration MacMahon made his way towards Ulster, but with a £100 bounty on offer for the apprehension of any Catholic bishop in Ireland he was obliged to lay low for many months, and it was not until March 1710 that he finally reached Clogher. On his arrival Bishop MacMahon met with the priests of his diocese, ‘all in private, of course, as it was not possible to hold a public conference’. He ‘frequently had to assume a fictitious name and travel in disguise’. He travelled about administering the sacraments, ‘especially the sacrament of confirmation . . . according as opportunity offered’.

Abjuration Act

In 1709 the Irish parliament passed the Abjuration Act, which obliged all priests to abjure the Jacobite pretender’s claim to the British throne. Any priest who had not taken the oath by 25 March 1710 was liable to arrest and deportation. The pope, however, decreed that no Catholic could take the oath. No priest in Clogher abjured. Bishop MacMahon reported to Rome that

‘. . . from that time the open practice of religion either ceased entirely or was considerably curtailed according as the persecution varied in intensity . . . priests have celebrated Mass with their faces veiled, lest they should be recognised by those present . . . I, myself, have often celebrated Mass at night with only the man of the house and his wife present. They were afraid to admit even their children so fearful were they. The penalty for anyone allowing Mass to be celebrated in his house is a fine of £30 and imprisonment for a year.’

In October 1712 MacMahon himself narrowly escaped capture at the hands of Edward Tyrell, the notorious priest-catcher.

Various Acts against ‘Popery’

Relatio status

In 1714 Bishop MacMahon penned his Relatio status, the best account of the Catholic Church and religion in any Irish diocese at that time. He reported that the greatest problem for the Catholic community in Ulster was its poverty:

‘Although all Ireland is suffering, this province is worse off than the rest of the country, because of the fact that from the neighbouring country of Scotland Presbyterians are coming over here daily in large groups of families, occupying the towns and villages, seizing the farms in the richer parts of the country and expelling the natives . . . The result is that the Catholic natives are forced to build their huts in mountainous or marshy country.’

With the Catholics impoverished,

‘the remuneration of their pastors is necessarily small and altogether insufficient . . . A more regrettable feature of the situation is that some priests have to celebrate Mass in soiled and tattered vestments—they cannot provide better. There are hardly any chalices of gold or silver in the diocese. Most are made of tin, not gilt even on the inside.’

And he didn’t even mention that his priests had no churches to serve in!

MacMahon lamented the shortage of clergy, with only 33 diocesan priests, a ‘few Franciscans and one or two Dominicans’, owing ‘not so much to a scarcity of vocations . . . but rather the result of economic factors’. The lack of priests meant that some of them had to serve areas of 12–15 miles across, ‘where formerly three or four priests ministered’. Some priests were obliged to celebrate Mass at two separate locations in their parishes on Sundays and holy days and, because of the distances involved, many parishioners could attend Mass only on alternate Sundays.

![Lough Derg in 1714. ‘Every year thousands of men and women of all ages come from even the most distant parts of the country to this [Station] island to make a novena . . . During the three months of the pilgrimage season Masses are being celebrated continuously from dawn till mid-day . . . An extraordinary feature of the pilgrimage is that none of the Protestants in the locality ever interfere with the pilgrims, although people are forbidden by law of parliament to make it . . . The result is that, while in the rest of the country the practice of religion has practically ceased as a result of persecution, here, as in another world, religion is practised freely and openly. This, people attribute to the mercy of God and the prayers of St Patrick . . . Many priests help on the island but the Franciscan fathers bear the brunt of the work.’ (Hugh MacMahon, Relatio status) Picture: Station Island, Lough Derg, in 1876, by William Wakeman. (Anne Cassidy)](/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/312.jpg)

Lough Derg in 1714. ‘Every year thousands of men and women of all ages come from even the most distant parts of the country to this [Station] island to make a novena . . . During the three months of the pilgrimage season Masses are being celebrated continuously from dawn till mid-day . . . An extraordinary feature of the pilgrimage is that none of the Protestants in the locality ever interfere with the pilgrims, although people are forbidden by law of parliament to make it . . . The result is that, while in the rest of the country the practice of religion has practically ceased as a result of persecution, here, as in another world, religion is practised freely and openly. This, people attribute to the mercy of God and the prayers of St Patrick . . . Many priests help on the island but the Franciscan fathers bear the brunt of the work.’ (Hugh MacMahon, Relatio status) Picture: Station Island, Lough Derg, in 1876, by William Wakeman. (Anne Cassidy)

Soon after arriving in Clogher Bishop MacMahon sent two priests to the Irish College at Antwerp for what would now be termed ‘professional development’. A good reflection of the importance that he ascribed to clerical education is the fact that he spent almost two years establishing a number of bursaries to support clerical students from Clogher and Kilmore in Continental colleges with money bequeathed by his uncle, Arthur MacMahon, provost of St Peter’s College, Cassel.

Bishop MacMahon informed Rome that he had appointed successors to priests who had either died or grown too infirm to minister. He found, however, that ‘the people of a parish sometimes are unwilling to accept as their pastor any priest except the priest they themselves choose’. Nonetheless, a list of priests drawn up by Mervyn Archdale and the other Protestant magistrates of Fermanagh in 1714 reveals that MacMahon had succeeded in reconstituting the Catholic Church despite very difficult circumstances.

The 1714 list shows that several of the priests registered in 1704 were still serving a decade later: Patrick Lynam at Inishmacsaint (aged 72); Patrick Murphy at Aghavea (aged 71); Charles McGealloge at Cleenish (aged 68); Art McCullin at Templecarne (68); William O’Hoyne at Enniskillen (66); and Turlough Connelly at Clones (68). The names of the priests of five other Clogher parishes in the 1714 list are different from those registered in 1704, however. Indeed, three priests were recorded as being ‘registered’ for Magheraculmoney (Culmaine on map) parish in 1714, though none of them was registered in 1704. Somehow or other, the registration process was subverted, either by new priests being substituted surreptitiously for those already on the register or simply through official confusion. One is left to wonder whether the only copy of the register had been forwarded to Dublin.

The list of 1714 identified a number of priests who were ‘unregistered’. They included Dominic MacDonnell, a former friar, who officiated in Drumully, and, in the same parish, Owen MacDonnell, who had recently arrived ‘from France or elsewhere’, and Edmond McGrath, who ‘came from beyond [the] seas’ and assisted the 72-year-old parish priest of Inishmacsaint. In addition, the magistrates identified ten Catholic schoolmasters in Fermanagh, among the county’s thirteen Catholic parishes, reflecting a striking level of pedagogical provision for the Catholic community there in extraordinarily straitened circumstances.

On 23 June 1714 the magistrates of Fermanagh ‘ordered attachments’ to apprehend the listed Catholic priests and teachers for refusing to take the oath of abjuration and ‘to bring them to justice’. What happened next is unclear, but James Kelly reckons that the smooth succession of George of Hanover to the throne of the late Queen Anne defused the Protestant fears that had prompted the 1714 crackdown in the first place. No one would have realised it at the time, but the very worst of the penal days were coming to a close.

Epilogue

The Report on the state of popery compiled in 1731 identified 50 diocesan priests in Clogher, and two deacons. Furthermore, there was a Franciscan friary at Lisgoole with ‘about 20’ friars, and a friary had recently been erected in Donaghmoyne. There were ‘nunneries’ at Carrickmacross and at Inishmacsaint. On the other hand, the 1731 Report shows that there were only nine ‘Mass houses’ or Catholic chapels in Clogher diocese, and that the one at Inniskeen had been erected only in the previous year. A Mass house was soon ‘going to be’ erected in Monaghan town. Significantly, seven of the Mass houses were situated close to County Louth. By contrast, there were no Mass houses in that part of Clogher diocese in Fermanagh, and only one in Tyrone. Mass was celebrated on 48–50 Mass rocks ‘in ye open fields’.

Templecarne Mass rock, Pettigo, Co. Donegal—one of 48–50 ‘in ye open fields’ throughout the diocese, according to the 1731 Report on the state of popery. (Maureen Boyle)

The fact that only one per cent of the 892 ‘Mass houses’ recorded for the whole of Ireland in 1731 were in Clogher diocese reflected the persisting poverty of the Catholic community where there had been a considerable influx of British immigrants. It also reflected something of the persisting sectarian passions among the Protestant community there. The experience of dispossession and of religious persecution affected the Irish Catholic community very profoundly indeed, and not only in Ulster. That experience resonated well into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. One cannot understand the modern history of Ireland without some awareness and understanding of the penal days. HI

Henry A. Jefferies is the Head of History at Thornhill College, Derry, and Visiting Fellow in the Academy of Irish Cultural Heritages in the University of Ulster.

Further reading:

S.J. Connolly, Religion, law and power: the making of Protestant Ireland, 1660–1760 (Oxford, 1992).

P. Corish, The Catholic community in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Dublin, 1981).

H.A. Jefferies, ‘The early penal days: Clogher under the administration of Hugh MacMahon (1701–1715)’, in H.A. Jefferies (ed.), History of the diocese of Clogher (Dublin, 2005).

J. Kelly, ‘The impact of the penal laws’, in J. Kelly and D. Keogh (eds), History of the Catholic diocese of Dublin (Dublin, 2000).