Patrick Pearse:proto-fascist eccentric or mainstream European thinker?

Published in

20th-century / Contemporary History,

Features,

Issue 6 (Nov/Dec 2010),

Revolutionary Period 1912-23,

Volume 18,

World War I

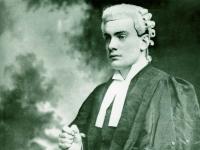

Patrick Pearse in his barrister’s robes c. 1914. (Pearse Museum)

Whatever one’s point of view, Patrick Pearse has always engendered strong emotions. Shortly after the Easter Rising he became widely revered, some even suggesting that he should be made a saint. In the decades surrounding the outbreak of the troubles in Northern Ireland, however, he was frequently described as a ‘fascist’. In 1978 Xavier Carty made a very passionate condemnation of Pearse’s celebration of the use of violence, and even argued that his writings ‘indicate a narrow fanaticism as well as an obsession with racial purity and the pre-eminence of a mythical Gaelic race suggesting that if he had not died at Kilmainham he might have been an Irish Hitler’. In recent years a more sophisticated view of Pearse has been developed in academic works, but in popular perception he is still seen as a proponent of doubtful ideas, while allusions to autism and homosexuality have also hit the headlines.

What Pearse said

The origins of this negative image of Pearse clearly lie in his writings. His sense of messianic duty associated with youth, rebirth and political violence indeed seems to come close to fascism. The most cited example for this stems from 1915, when he welcomed the First World War:

‘It is good for the world that such things should be done. The old heart of the earth needed to be warmed with the red wine of the battlefields. Such august homage was never before offered to God as this, the homage of millions of lives given gladly for love of country.’

It is not too difficult to find other examples of such extremism in his work, which, when put together, make for some unsettling reading.

Much of this started with the strong emphasis on patriotism, which also permeated the curriculum presented to his pupils at

St Enda’s. In the school prospectus of 1908 their duties were clearly spelled out: ‘It will be attempted to inculcate in the pupils the desire to spend their lives working hard and zealously for their fatherland and, if it should ever be necessary, to die for it’. Pearse felt that what he saw as a feminised society should recover the ideals of courage, strength and heroism. Through war, he argued, it was possible ‘to restore manhood to a race that has been deprived of it’. In this the shedding of blood was even considered a good thing:

‘I should like to see any and every body of Irish citizens armed. We must accustom ourselves to the thought of arms, to the sight of arms, to the use of arms. We may make mistakes in the beginning and shoot the wrong people; but bloodshed is a cleansing and a sanctifying thing.’

Only through war could Ireland be really freed from the English presence:

‘It is evident that there can be no peace between the body politic and a foreign substance that has intruded itself into its system: between them war only until the foreign substance is expelled or assimilated.’

Stained glass window in St Philip’s Church of Ireland church, Dartry, Co. Dublin. Pearse was not the only one preaching the heroism of war or the beauty of sacrifice at this time. (Sonia Gyles)

Certainly a way of putting things which reminds one of Adolf Hitler and his attitude to Jews.

Pearse also compared the sacrifices necessary to those of Christ: ‘It had taken the blood of the son of God to redeem the world. It would take the blood of the sons of Ireland to redeem Ireland’. And he compared the Irish people to the Messiah: ‘the people labouring, scourged, crowned with thorns, agonising and dying, to rise again immortal and impassable’. In his stories he took this a step further: ‘One man can free a people as one man redeemed the world. I will go into battle with bare hands. I will stand up before the Gael as Christ hung naked before men on the tree’. To counter concerns that England could not be beaten militarily, he emphasised that God was on the Irish side in a reasoning that comes close to that of a jihadist:

‘Always it is the many who fight for the evil thing, and the few who fight for the good thing; and always it is the few who win. For God fights with the small battalions. If sometimes it has seemed otherwise, it is because the few who have fought for the good cause have been guilty of some secret faltering, some infidelity to their best selves, some shrinking back in the face of a tremendous duty.’

To underline the extremism of this thinking, commentators have often pointed to James Connolly’s reaction to Pearse’s celebration of the ‘red wine of the battlefields’ in 1915:

‘No, we do not think the old heart of the earth needs to be warmed with the red wine of millions of lives. We think anyone who does is a blithering idiot. We are sick of such teaching, and the world is sick of such teaching.’

Connolly, however, was certainly not representative of mainstream thinking in Europe at that time. Indeed, if we look at contemporary public discourse we find surprising similarities with Pearse’s ideas.

Widespread cult of sacrifice

During the First World War it was certainly not uncommon to preach the heroism of war or the beauty of sacrifice. In his War Sonnets Rupert Brooke emphasised the honour and nobility associated with dying as a soldier, and used the same metaphor as Pearse about a ‘world grown old and cold and weary’. Among German officers at this time a cult of sacrifice developed in which they venerated fallen comrades who had shown ‘boundless initiative, inordinate capacity for suffering and blind self-sacrifice’.

The celebration of patriotism had also become widespread in the education systems of many western countries in the late nineteenth century. The most notable example was the introduction of the Pledge of Allegiance in American schools in 1892. The praise of a short and heroic life was equally widely sung. Even James Joyce, who fled Ireland because of its narrow-minded nationalism, argued in his story The Dead that it was better to ‘pass boldly into that other World, in full glory of some passion, than fade and wither dismally with age’. Winston Churchill espoused similar ideas in 1908: ‘What is the use of living, if it be not to strive for noble causes and to make this muddled world a better place for those who will live in it after we are gone?’ The celebration of the hero in mythology and the emphasis on manly virtues were also evident in the popularity of the operas of Wagner.

Socialists

Virtually every aspect of Pearse’s thinking can be found among socialists of different hue at that time. In particular, since the Paris Commune of 1871 a militarisation of their thinking had taken place. Sacrifice, martyrdom, heroism and even redemption were emphasised. This can be seen most clearly in the statement made by Karl Liebknecht after the Spartakists’ attempt at revolution in Germany failed in 1919. He started off by saying that ‘there were defeats which were victories; and victories which are more fatal than defeats’ and then continued:

‘They died gloriously; they fought for something higher, for the noblest goal of the suffering humanity, for the spiritual and material salvation of the starving masses, they have shed blood for a holy cause, which has thus been sanctified. And from every drop of their blood, this seed of dragons for the winners of today, will rise the fallen Avenger, from each damaged fibre new fighters for the higher cause, which is eternal and imperishable as the firmament. The vanquished of today will be the winners of tomorrow.’

If the starving masses are read as the Irish, this could easily have been said by Pearse directly after the Rising.

During the war the glorification of bloodshed as a cleansing experience was also widespread. Even a peace-loving man like Thomas Mann, who would later win the Noble Prize for literature and became an active opponent of the Nazis, described the war in 1914 as ‘a purification, a liberation, an enormous hope’. In Ireland this also had a long pedigree. The popular writer Canon Sheehan wrote in 1914 in his novel The graves at Kilmorna: ‘As the blood of martyrs was the seed of saints, so the blood of the patriot is the seed from which alone can spring fresh life, into a nation that is drifting into the putrescence of decay’. The comparisons to Christ and the road to redemption were also not uncommon. Even James Connolly, who was essentially an atheist, spoke about a rebellion in those terms: ‘we recognise that of us, as of mankind before Calvary, it may truly be said “without the shedding of blood there is no redemption”’. The same applies to the aforementioned Karl Liebknecht, who argued that ‘still the road to Golgotha is not completed for the German workers—but the day of redemption is near’.

‘Moving away from the dungheap and the turf-rick’

It was not only his ideas on patriotism, sacrifice, war and redemption that fitted in with European currents. Pearse’s thinking in all areas concurred with and was often directly inspired by European counterparts. He read international newspapers and literature, and corresponded with a number of like-minded figures abroad. His emphasis on the language as a tool to regenerate Irish culture and nationality was based on foreign examples and was shared with many separatist and regionalist movements throughout Europe: ‘The moral of the whole story is that the Hungarian language revival of 1825 laid the foundation of the great, strong and progressive Hungarian nation of 1904. And so it shall fall out in Ireland’.

Although initially arguing that ancient Irish writers were even better than the writers from Greek and Roman antiquity, he soon became one of the strongest proponents of a modern literature in Irish. In his view, Irish literature should be taken from ‘the Anglicised backwaters into the European mainstream’. He strongly criticised the focus on Irish rural life of most Irish contemporary writers and called upon them to deal with the modern world: ‘Let us move away from the dungheap and the turf-rick; let us throw off the barnyard muck’. In this attack on convention and false sentiments in literary writing Pearse was in tune with the contemporary literary sensibilities of Europe and America, which he knew well.

Views on education

Pupils gardening at St Enda’s, Rathfarnham. Pearse had come into contact with Welsh, Belgian and other international proponents of the New Education Movement who all argued that the needs of individual children should be central in teaching and opposed the restriction of education to the three R’s. (Pearse Museum)

His international orientation also deeply influenced Pearse’s thinking in the field of educational policy. He had come into contact with Welsh, Belgian and other international proponents of the New Education Movement who all argued that the needs of individual children should be central in teaching and opposed the restriction to the three R’s. His actual policies were developed slowly by the study of educational theory and the practices in other countries. The special place he gave to the inculcation of patriotism was, for instance, the result of his study of the educational system in the USA. Much of his emphasis on the direct method and his use of modern teaching aids such as cut-out figures were directly inspired by his visit to Belgian schools in 1905.

A final example of Pearse’s awareness of European developments is his use of the pageant as a means to impress mythological and heroic examples on his pupils. The popularity of public pageants and dramas based on historical themes was also a pan-European phenomenon at that time. In one of the first editions of Pearse’s school newspaper, An Macaomh, an article was reprinted dealing with the return of pageants to Europe. They subsequently became one of the main cultural activities in the school. In 1913 a public performance by the ‘St Enda players’ was clearly greatly anticipated by the Gaelic League newspaper: ‘It may be assumed that the pageants & pageant plays will be the most beautiful things of the kind that have been in Dublin’.

The picture that emerges here clearly places Pearse in a European context. Most of his ideas were directly inspired or even borrowed from outside. His thinking was in no way conservative or retrograde. Apart from his extremist militarism and nationalism, which were widely shared, his ideas on educational and literary thinking were clearly modernist. They also concur with his radical ideas on workers’ and women’s rights. All this can only lead to one conclusion: that Pearse was an exponent of his time, and represented ideas widely held in Europe and beyond. HI

Joost Augusteijn is a lecturer in European History at Leiden University. His Patrick Pearse: the making of a revolutionary has just been published by Palgrave, Macmillan.

Further reading:

R. Higgins & R. Uí Chollatáin (eds), The life and afterlife of P.H. Pearse. Pádraic Mac Piarais: saol agus oidhreacht (Dublin, 2009).

S. Ó Buachalla, A significant Irish educationalist: the educational writings of P.H. Pearse (Dublin, 1980).